The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

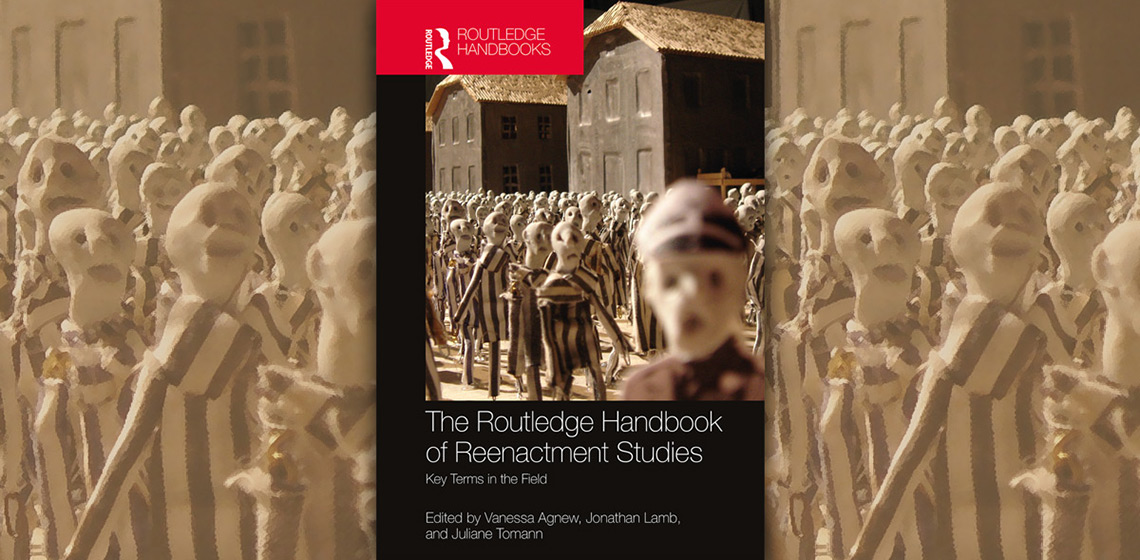

Book Review: The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies by Agnew, Lamb & Tomann (eds)

Re-enactment studies are booming, just like re-enactment, living history and role play are. This handbook, therefore, is a good introduction for those interested in the more academic aspects of re-enactment. However, as is often the case with an academic-only approach, this book is not meant for those interested in the backgrounds of re-enactment per se. The authors are academics, writing for their peers; there are hardly any practitioners involved. The whole book feels like we are reading the reports of cultural anthropologists who have done a bit of fieldwork. The History of the Field (Otto), for example, is a history of the academic approach, not of re-enactment itself. This book is an aid to academic re-enactment studies programs, but does not support the emancipation or professionalisation of re-enactment itself.

In each of the 47 very short articles, one keyword is discussed in relation to re-enactment. As usual with such a themed volume, the messages are very mixed, and unfortunately they do not cross reference each other. The book would have improved if papers were circulated between the authors prior to publishing. Although the editors describe their ambition in their introduction, there could have been more vision for the future of the field. This too could have been accomplished by a good discussion between the authors. What is also missing are good definitions. As it stands, the keywords each are defined with their own chapter, but these are discussion papers or introductions, and are not meant to cover the single subjects fully.

It is guesswork why some articles made it and other themes did not. Some keywords do not have their own chapter, but are included over several articles, like interpretation, museum theatre, storytelling or time travel. LARP should possibly have had more attention than just be part of role play. Also, museums and heritage sites are not discussed in separate articles. However, a few good choices were made, like the article on gaming and the introductions into expertise & amateurism and indigeneity. Interesting keywords one would not expect are included; for example, forensic architecture, the Hajj (as the re-enactment of a number of rituals), martyrdom, and Mitzvah and memorialization.

Introduction chapter

Starting the book, Agnew, Lamb & Tomann try to answer the question as to what are re-enactment studies? They discuss in short how the definition of re-enactment itself changed over time, and that re-enactment arguably is as old as the world itself.

Structured reflection in various other disciplines led to re-enactment studies, a new and relatively unstructured academic territory. Platonists and empiricists are brought to the spotlight, possibly as examples of how scientific discussion of re-enactmentcan be successful. The authors are aiming to justify the inclusion of re-enactment studies as an independent branch of academic research. This book would help to earn that field a place at university. Previously, as the authors put it, “a decade ago, the nascent field was most closely allied with public history and museology, the intervening period has seen a shift away from history” (page 7), towards performance studies. This introduction concludes with the thought that while interest in re-enactment will grow, a corresponding interest in a scientific approach may also expand.

Experimental archaeology

The contribution on experimental archaeology mainly covers historical aspects of the field. Schöbel attempts to structure experimental archaeology and refers for that to EXARC without basis. Schöbel himself would prefer if experimental archaeology followed a natural-science approach only (“experience and experiment are to always be kept distinct from one another”, page 71). In fact, experimental archaeology is lauded because of its innovative and multidisciplinary character, connecting better to the natural sciences than most of the traditional archaeological approaches (Kropp, in Paardekooper 2019). Its acceptance is partly due to the application of a more traditional scientific structure with "hard" and "soft" sciences coming together (Little, in Paardekooper 2019) which is exactly why experience cannot be excluded from experimental archaeology. While seeking to become more scientific, one should not forget that we are studying human behaviour.

Schöbel continues by stating that “Re-enactment and living history foster new insights without, however, providing new knowledge, and thus serve education and personal development” (page 71). He does not see re-enactment as part of the scientific discourse, unlike experimental archaeology. This nips cooperation between experimental archaeologists and re-enactment study scientists in the bud.

Expertise and amateurism

Brædder gives a bit of background about historic accuracy levels of reenactors, starting with Strauss’ division between “hardcore”, “progressive”, “mainstream”, and “farb”. She then discusses follow-up research by Thompson. More recent work in Denmark about what constitutes expertise within respective re-enactment communities leans on this, but where previous research focused on outer appearance, recent studies into how authenticity is constructed in re-enactment groups goes more in-depth. Is it materials, the use of tools or feelings? Each group defines this in their own way, as they are not under the authority of any museum or other organisation. Brædder gives a glimpse of a potentially very interesting future for the studies of re-enactment as cultural anthropology.

Gaming

In this short article, van den Heede explains how historic virtual worlds are an important asset of gaming. These games act as a form of re-enactment where “participants act out behaviours and attitudes that are believed to have existed in the past, in order to personally and affectively experience this past and seemingly access it in a direct manner” (Agnew, 2004; 2007; Cook, 2004, in van den Heede, 84). Obviously, games are not representative, partly because they are male-dominated, entertainment-oriented, militaristic and Western-centric. Actions in the games are limited, the experience predefined. How much is the historic aspect only a narrative, an alibi to score points, shoot other players, and be entertained? Historical accuracy is an almost absent phrase here. Recently, this seems to improve, with more alternatives to the ‘classic’ gaming scenario popping up. These new games can be an alternative for visiting a museum if it comes to learning goals.

Indigeneity

Edmonds takes us into the world of indigenous re-enactment, which has a clear political aspect in it. Whoever thinks that re-enactment can be value-free should think again, and take responsibility. Edmonds mentions how indigenous people were brought to Europe for show in the 18th and 19th century, re-enacting an imagined, authentic “savage” past to legitimise the role of the colonists. It is time to look into the re-enactment by indigenous people themselves, as this is a complex and interesting matter. This re-enactment is an important form of protest, and can be a sometimes emotionally supercharged way of cross-cultural negotiation. Edmonds does not show a solution or a way forward, she merely points to the existence of indigenous re-enactment. Having noticed its complexity, you will better understand its role.

This book is a good introduction, touching very briefly on many aspects of re-enactment studies. It will aid the development of this academic field, but is not for re-enactors per se. The future will tell if it benefits the academic world to work without the input of practice and practitioners as is seen in this book.

Book information:

The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies. Key terms in the field.

Edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb and Juliane Tomann

2019, ISBN 978-1-138-33399-4, London: Taylor & Francis, 264 pp.

Keywords

Bibliography

Agnew, V., 2004. What is Reenactment?. Criticism, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 327–339.

Agnew, V., 2007. History’s Affective Turn: Historical Re-enactment and its Work in the Present, Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice [special issue], vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 299–312.

Cook, A., 2004.The Use and Abuse of Historical Reenactment: Thoughts on Recent Trends in Public History. Criticism, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 487–496.

Paardekooper, R., 2019. Experimental Archaeology: Who Does It, What Is the Use?. EXARC Journal, 2020-2. Available at: < https://exarc.net/issue-2019-1/ea/experimental-archaeology-who-does-it-what-use > [Accessed 27 May 2020]