The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

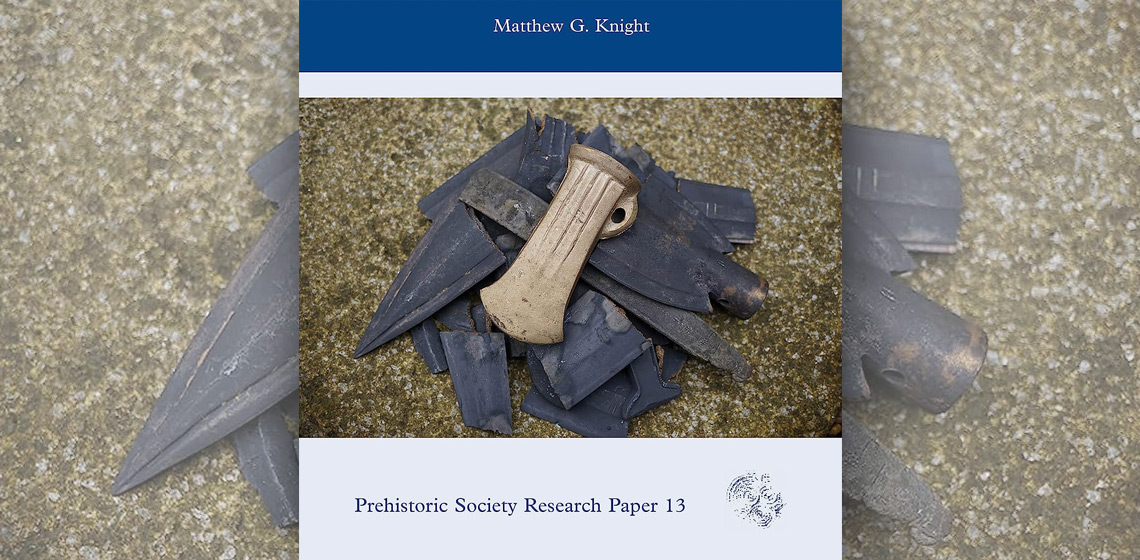

Book Review: Fragments of the Bronze Age by Matthew G. Knight

In this book, Matthew Knight examines fragmentation of metal objects from hoards dating to the Bronze Age of South-West Britain, and uses experimental archaeology to better assess fragmentation and destruction. Fragmentation is the deliberate destruction of metal objects. Other forms of destruction can include bending, folding, or crushing objects so that they are no longer useable.

Destruction and fragmentation of metal objects is a popular area of study in experimental archaeology. Creation and destruction require technical skills. But beyond the physical act, there is the question of why this was done. Knight combines theoretical and practical approaches in order to understand the relationship between people, performance, and objects. His interpretations of technical knowledge and performance are the result of examining both the biography of the object, the biography of destruction, and the conditions of deposition. The author asks if we, as researchers, can identify the skills needed and understand the processes of fragmentation.

Knight begins his work with scholarly research and then combines this with data collected from experimental archaeology where he explores the various types of damage done to metal objects. Knight introduces us to the practice of fragmentation with a modern story in Ethiopia about a peacekeeping rite where spears are burned and destroyed. Those who have studied weapon hoards will recognise this description of the broken shafts and damage done to the spearheads. Knight also describes a tradition in South Sudan where metal armbands worn by the deceased are broken during funeral rites and the fragments are distributed among mourners. While ethnographic studies cannot be taken as an explanation for events in the Bronze Age, it does give us an illustration about the significance of fragmentation and deposition as part of communal ritual acts.

The book provides a chronological survey of fragmented metal and deposits found in South-West England starting in the Chalcolithic and continuing through the Later Bronze Age. In these chapters Knight describes the types of objects that were included in depositions along with how the objects were treated. For example, Early Bronze Age objects suffered minimal damage, while as time progressed objects were subjected to increased damage including breakage, bending, or crushed or filled sockets.

The second chapter will be of particular interest to researchers in experimental archaeology where Knight defines and quantifies intentional damage and wear analyses, including repairs. The chapter is well illustrated with photographs of the different types of damage seen on swords, spearheads, and axes that were used in multiple experiments. The results are quantified in a system for ranking damage.

The Damage Ranking System incorporates the mechanics of damage and fragmentation; quantifying and defining the various types of damage to weapons. The ranking system includes data such as post-casting processes, the types of damage and associated marks, and the tools used to create damage. This system can be applied to future experiments performed by others, or when examining museum objects. The system gives us the tools to better understand if damage occurred as a result of use or was performed as a final act before deposition.

While Knight’s book provides much needed data and systematic organisation for experimental archaeology, it also provides insights as to how depositional practices changed through time and location. The author explores how relationships were managed through the treatment of objects. The book connects ideas about death and transformation with the destruction of objects and considers how these objects could express relationships among social groups, or the ties between the living and the dead.

Those working with metals in experimental archaeology will find this book invaluable for assessing their own experiments. The Damage Ranking System provides a common denominator to share and publish data gained from experiments in a meaningful way, in addition to being able to compare experimental work with objects observed in museums. However, equally valuable is the consideration of why these acts were preformed and the significance to the Bronze Age societies in which they occurred.

Book information:

Fragments of the Bronze Age: The Destruction and Deposition of Metalwork in South-West Britain and its Wider Context. 2022. Matthew G. Knight. Prehistoric Society Research Paper 13, Published by Oxbow Books

ISBN 978-1-78925-697-0

Keywords

Country

- United Kingdom