The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

A Tablet Woven Band from the Oseberg Grave: Interpretation of Motif and Technique

In this article, the intention is to show the documentations behind the reconstruction of a tablet woven band from the Oseberg discovery catalogued as 13B2. Parts of the band are well preserved, and it is possible to interpret motifs and techniques with considerable confidence. Some parts are poorly preserved and are not possible to interpret clearly. By analysing the band, criteria were developed as a framework for experiments with the diffuse and destroyed parts. In addition to these criteria, short reviews have been made of five other fragments (four bands and a decorative textile) with similar motifs and techniques from the same find. The intention was to compare the clear and unclear parts of 13B2 with similarities and differences in these fragments. The experiments consisted of several drawings and weave tests of possible designs of motifs and techniques. Weave experiments were performed with simple tools that are very similar to tools found in the Oseberg grave and different thicknesses of yarn, ply degree, and colours. Based on the criteria for experiments and the comparisons with motifs and techniques in the other fragments, two versions were developed, one of which satisfied all criteria. The reconstruction result can largely be said to be analogous of the original: motifs and techniques have an authentic aesthetic expression.

Introduction

The textile fragments from the Oseberg tomb (834 AD) in Norway are considered the world's largest and most important textile finds from the Viking Age. Among the textiles, 48 tablet-woven bands were identified and roughly divided into five categories by Margareta Nockert: I) Brocade, II) Tabby, III) Mixed I and II, IV) Ready threaded and V) Three or more colours without brocade (Nockert, 2006, pp. 147-155). Approximately half of these bands are mounted in the tapestry weave, while none of them have been found mounted into garments. Ten bands have previously been published and categorized in Table 1 (Skogsaas, 2019a; 2019b; 2020). The main goal of this article is to give a reinterpretation of motifs and techniques in band 13B2 (See Figure 1a and 1b)1 .

In my studies of the tablet woven bands from Oseberg, I identified how motif construction is largely symmetrical, logical, and perfectionistic (Skogsaas, 2019a; 2019b; 2020). This will be included as reflections in the analysis and interpretation.

| Tablet weaving techniques: | Warp twisted: | Plain weave: | Mixed: | |||

| Ready threaded-tablets equally turned: | Regular and partial change of turning direction: | Individual change of turning direction: | Tabby: | Twill: | Different types of ground weave with brocade | |

| Catalogue number: | 12L1 | 6A narrow 15D 27D/27J2 30B | 6A wide | 30C | 30C | 13B2 34D |

Table 1. Categorization of ten tablet woven bands from the Oseberg find (Skogsaas, 2019b; 2020).

The reinterpretation is based on comparisons of new and old photos of 13B2 (Skogsaas, 2020), old drawings by the illustrators Sofie Krafft and Mary Storm (Skogsaas, 2020) and text by Margareta Nockert (Nockert, 2006). It is also based on interpretation of four other fragments of similar bands, a tapestry/bedcover from the Oseberg find, and an extensive amount of experimentation in practical weaving and pattern drawing.

The text structure

A traditional way of structuring a scientific article is to divide into description of methods, materials, analysis, discussion, and results. This is a long-standing work where the material has gone through many hermeneutical circles. In this article, it has been chosen to introduce the general method. Then, previous interpretations and discussion of the textile material (including motifs and techniques) are presented, which in turn leads to issues for experimentation built up by two headings: ‘Description of Oseberg 13B2’ and ‘Four other bands and a tapestry fragment’. This way of structuring the article means that the topics: method, materials, technique, and analysis are brought into these sections so that the reader can follow the work process all the way including the section about ‘Experiments and results.’

Method

Themes used for analysis of tablet woven bands are based on weaving techniques in Table 1 and the analysis themes by Lise Raeder Knudsen: motifs, number of threads in the warp and the weft, number of tablets and assessment of materials and of colours (Raeder Knudsen, 2014a). Few of the bands from the Oseberg grave are very well preserved, and the reverse cannot be studied in most cases, as with this band. They are either mounted in petrified textile fragments, on the substrate on which they lie, or they are too fragile to be touched. The condition of the fragments determines whether it is possible to reconstruct them with great probability or not. Four categories of preservation are used as the basis for analysis (Raeder Knudsen, 2014a p. 38):

| Very well preserved: | Most of the band is preserved, many details can be seen, and it can be decided with great certainty how the band looked. |

| Well preserved: | Fragments of the band are preserved at full width so that both edges can be seen. Types of warp and weft yarn, spinning and twist direction can be seen. |

| Less well preserved: | Only small fragments are available for analysis, making it less possible to get an overall impression. Types of warp and weft yarn, spinning and twist direction can be seen. |

| Poorly preserved: | Characteristic structure of tablet weaving can be seen, but other details are not available. |

13B2 is in the state of preservation from well to poorly preserved. The course of warp and brocade threads are possible to follow to a certain degree, but there are sections that are in too poor a condition to be interpreted, and these will be the subject of experiments. The reconstruction of motifs and weaving techniques can be estimated as probable or likely but cannot be called a replica with only one possible interpretation. The goal is to make a reconstruction that gives an authentic aesthetic expression: the most probable motif and weave technical result, conforming to the original band.

There are three ways to collect data in textile research: visual techniques, chemical techniques, and experimental ones (Raeder Knudsen, 2014a, p. 2). The first two fall mainly into the positivistic perspective, while experimenting involves adopting both the positivistic, the hermeneutic and, in particular, the phenomenological. The researcher is the source of understanding in the face of the studied phenomenon in an experiment, and it is through interpretation and a hermeneutic approach that the phenomenon acquires meaning. The researcher’s theoretical and practical competence within the studied phenomenon becomes essential in interpreting details that do not meet expectations (Raeder Knudsen, 2014b, p. 2). The importance of high practical competence cannot be emphasised enough in exploring ancient craft techniques. Asking with an open mind is challenging, but necessary to think in other ways about techniques other than the well-known ones. Some techniques and aesthetic expressions in historical bands may be of such a nature that they must be woven in a way that falls outside the usual rules of tablet weaving today. Similar reflections were made by two tablet weaving researchers in an article on the discovery of a new tablet weaving technique from the Iron Age (Raeder Knudsen and Grömer, 2011, p. 95). In his analysis of the tapestry from Oseberg, Bjørn Hougen described the weaver’s great competence in ‘drawing’ elegant lines and complicated patterns (Hougen, 2006, pp. 112-113).

Two approaches have been used to develop the most likely results for those parts of the band that are poorly preserved: 1) Experimentation with drawing motifs and testing of weaving techniques and 2) comparison with old black and white photographs of four other brocaded bands, which show similar motifs. Criteria (see the summary in the end of the next chapter) have been set up for experimenting with some visual parts that are repeated in several places in the 13B2 band fragment: parts that are crucial for understanding the poorly preserved parts. The tests are performed based on this set of criteria. The weaving tools used in the experiments are very similar to those found in the Oseberg grave. The tablets are slightly larger, but that is completely irrelevant to the result. Data from experimenting with weave tests and pattern drawing have been used on the principle of analogy: comparison of the experimental result with the original to identify similarities and differences (Lammers-Keijsers, 2005, p. 19).

Description of Oseberg 13B2

The previous understanding of technique and motifs present in 13B2 is given a new interpretation in this article. There are parts of the band that are clear and interpretive and thus serve as a starting point for experiments with the uncertain parts. The chapter begins by interpreting the clearer parts of the motifs. These interpretations become the framework for experiments with the poorly preserved and diffuse parts. To support interpretations of these challenging topics in the work with 13B2, four similar bands from the Oseberg discovery are included to compare motifs and technique: 15A1 (the band in a tapestry with birds), an ‘unfinished band’ and two other bands documented as 26E1 and 27H. Some reflections around a decorative textile in another weave technique, a coarser fabric quality is also included: Oseberg 18C.

The tapestry fragment is described as '13B2 Skjoldborg': a warrior scene with men lined up with shields (See Figure 2). The band is preserved to its full width, approx. 2.5 cm (See Figure 1 and 2). Both selvedges can be seen, having a triangle motif. The band is in a petrified textile fragment, and the reverse cannot be studied.

The motifs were interpreted by the illustrator Mary Storm in 1940 as a geometrical pattern with small rhombuses inside diagonal frames forming rectangles (See Figure 2 and 3ab). The motifs are also interpreted as rhombuses by Nockert: the brocade thread covering the rhombuses is in loosely spun two-ply wool and mostly reddish (Nockert, 2006, p. 158). The brocade technique is probably similar to that is interpreted in Oseberg 34D: The brocade threads, which are not on the surface, dive to the reverse side of the band, instead of passing through the main shed, as in the Birka bands (Skogsaas, 2019, p. 59).

The warp threads are in wool, and most likely there had also been threads with plant material in the warp, left as residues and indentations in the textile. The main weft in plant material had crumbled away. Yarn and colours will be described and discussed in detail later in this article.

During the previous research of the 13B2 band (Skogsaas, 2020), the band was interpreted to have been woven with 29 pattern tablets and six tablets in each selvedge (41 tablets) and approximately 3 cm. wide. It was also established that the band had been most likely woven with two threads per tablet, but due to deteriorated parts, the pattern for the reconstruction was partially based on Storm's drawing and Nockert's text and was interpreted as in Figure 4a. The technique was interpreted as double turns (180° turns) of the tablets.

After the book about tablet woven bands from the Oseberg discovery was published, one of my test weavers, Sylvie Odstrčilová, drew my attention to some differences between my reconstruction and the photo of the original 13B2 band (See Figure 1a and 1b), suggesting the possibility that there had been a different weaving technique in parts of the band and possibly a slightly different motif. Odstrčilová also commented that it also could be different colours in the brocaded threads. Based on a number of interesting discussions and demonstrations of motif and technical understanding, a sketch of the main figures came up in Figure 4b (Numbers refer to what I later describe as central points for experiments with the rectangle).

The brocaded motifs seem to have been brocaded with threads in different colours (discussed later). The band is still interpreted as woven with two threads in the tablets, but perhaps in a mixed technique of different numbers of turns of the tablets: single turns of the tablets in the framing of the W and the two small motifs (wide blue marks) and double turns (narrow blue marks) in the rectangle (see Figure 4b). These two main motifs (W-motif and rectangle-motif) are repeated as mirror images in the second half of the fragment. The W and small motifs are better preserved and give a clearer interpretation than the rectangle section that is mostly poor preserved. Points 1 and 2 in Figure 4b will later be described as essential to the development of the design of the rectangle and for performing the experiments.

If the first analysis above is correct, the technique with single turns of tablets in the W and the two small motifs connected to the W, then it’s similar to the ground weave in the Vestrum band (not brocaded), dated 400AD, found a few miles from Oseberg (See Figure 5). The tablets in this band were probably threaded so that every other tablet is placed with an empty hole against the threaded hole, except the two centre tablets which are threaded against each other: ZS. Peter Collingwood has described this technique as ‘half the cords not twined between successive picks, using two threads per tablet’ (Collingwood, 2015, p. 123).

The W, the small motifs and techniques

To assess the number of tablets in the central pattern section of 13B2 band, the brocaded wefts in the individual parts of the W and the small motifs were counted piece by piece (See Figure 6a). The whole width was then established, based on the final count of brocading wefts, the number of alternating wool and missing-plant material lines in the pattern and the assumptions I could make about the technique in these parts.

In Figure 6b, it is possible to see quite clearly that the neighbouring warp threads in wool lines overlap, showing that each of them passes over two wefts: two red dots representing two missing plant material wefts for each warp thread in wool (blue). This led to the understanding that single turns of the tablets were used in this section of the band, and each line is two tablets wide.

After extensive counting I concluded that the two small triangular motifs (above and below the W) are built up of 12 tablets in the horizontal direction and 19 brocaded threads in the vertical direction. Then it is a very likely result that the pattern is built up of 34 tablets (12 + 12 + 10).

The rectangle and techniques

A complete rectangle does not exist to be interpreted. Individual parts of the rectangle are studied in different places of the band to understand the most likely interpretation (See Figure 1a and 1b). As the condition of the motifs and technique inside the rectangle is so unclear, it was decided that the best start would be in interpreting the corners. Point 1 (See Figure 4b) is identified as a double point formed by ninth and tenth tablets of the pattern - in the space between the small motif and W. The other rectangle corner touches the selvedge border in point 2 probably in one weft pick (See Figure 7a), or is slightly cut off by the border, so that the part of the corner touching the border consists of three weft picks (See Figure 7b).

At this stage in the work, it was not possible to decide if the dots were surrounded by a narrow or wide wool and linen frame, because the width of the frames looked different in different parts of the band. An assumption is that the inner frame of the H and the frame around the dots can be woven with single turns that give two wefts/picks (white marks) for each stitch (blue) in Figure 7c. In the same Figure nine to ten brocade wefts (red marks) are identified in each half of the H, but there can also be up to eleven wefts (green marks). The link between the two legs is quite damaged, but it seems to be built up like in Figure 7c.

To develop a deeper understanding of the pattern, it was experimented with rectangle corners built up with two and three rows, and how they affect the framework for the design of the rectangle and the motifs inside. In the following text, short descriptions of a tapestry fragment and four similar bands will support the experiments and interpretations.

Yarn material and colours

As the goal is to make a reconstruction that gives an authentic aesthetic expression (the most probable motif and weave technical result consistent with the original band), the yarn is also a part of this. The dominant sheep breed in the early Viking Age is believed to have been a 'goat-horned' sheep breed with short tail (Hoffmann, 1964 cited in Ingstad, 2006, p. 187). Norwegian wild sheep and Old Norse sheep have genes from this breed. In the Oseberg textiles, there are no polygonal hairs found, and it is possible the wool was cut and not rooed (Rosenquist cited in Ingstad, 2006, p. 188). The yarn in the Oseberg textiles has been analyzed as dominated by Z-spinning in the warp and S-spinning in the weft (Rosenquist, 2006, p. 189). Similarly, it appears to be in the warp in the bands as well (Skogsaas, 2020). In the bands, no measurement of yarn thickness or twist and fiber counting has been done. In most of the Oseberg bands the twist is mostly strong to very strong. In 13B2 the warp seems to have a strong twist. The brocade threads are in very loose twist. The colour of the yarn in the warp is today medium dark brownish. It is not possible to exactly estimate the original colour either in the main pattern, or in the thicker outer and inner edge cords, possibly as in Figure 4b. We know nothing about the plant material yarn in 13B2: It has probably been very thin and two-ply in the warp and even thinner and two-ply or one-ply in the weft. Yarn in plant material might have been hemp, nettle or flax, but it is very likely that it was flax (Rosenquist, 2006, p. 173).

Summary and criteria for experiments with the rectangle in 13B2

This summary of clear and probable interpretations of 13B2 set the framework for experiments with the rectangle motif:

- The band’s total width is made up of 34 tablets (12 + 12 + 10). The design of the W and the small triangular motifs is 12 tablets wide and includes 19 brocaded threads in the vertical direction.

- The short sides of the rectangle are made up of two narrow diagonals in wool and one line of plant material in between.

- The long sides of the rectangle are built up of three narrow diagonals in wool and two in plant material in between.

- Rectangle corner in Point 1 (in the space between the small motif and the W in Figure 4b) is identified as a double point formed by the ninth and the tenth tablet of the pattern.

- Rectangle corner in Point 2 (Figure 4b) meets the selvedge between one and three rows.

- Nine brocade wefts (two tablets wide) are identified in each half of the H, probably a maximum of 11.

- The dots in each end of the rectangle are made up of three brocaded rows (two tablets wide).

Description of four similar bands and a tapestry fragment

By including four other bands (two of them mounted in the Oseberg tapestry), all with probably the same techniques as 13B2, the intention is to compare the certain and uncertain interpretations of 13B2 with similarities and differences in the design of these bands. In all the four bands and the tapestry, the motif H is repeated. It gives an idea that the design is highly valued as none of the other motifs from other Oseberg bands had been reproduced so many times. It is possible that it represents the old Norse rune H in the Elder Futhark, with spiritual and divinatory use (Det store norske leksikon).

Catalogue number 15A1

This band is too badly preserved to give anything other than a glimpse of a similar design of the geometric motifs as in 13B2. 15A1 shows a stylized tree with six birds with a shape reminiscent of ravens with large beaks (See Figure 8a).

Enlargement of the band in Figure 8a: Figure 8b. One of the motifs looks like a rectangle with an H inside (yellow). Another motif has some similarities to the W motif in 13B2 (blue).

Catalogue number 18C

Fragment 18C is a decorative textile in a coarser wool material than was used in the tablet woven bands. A rectangle with two dots at each end of an H is part of a larger pattern in the textile2 . The motif is almost identical to the rectangle in 13B2, only in a different weaving technique (See Figure 9a). The outer frame of the rectangle has three lines in the short and the long diagonal. The inner frame of the H and the dots and the outer frame look narrow but are made with two wefts/picks each warp thread.

The band known as Snartemo V is a tablet woven band from Snartemo, Norway 550 AD. It is two-sided and in a floating technique. The only reason to show this band in this article is because of the two H’s (See Figure 9b).

An unfinished tablet woven band

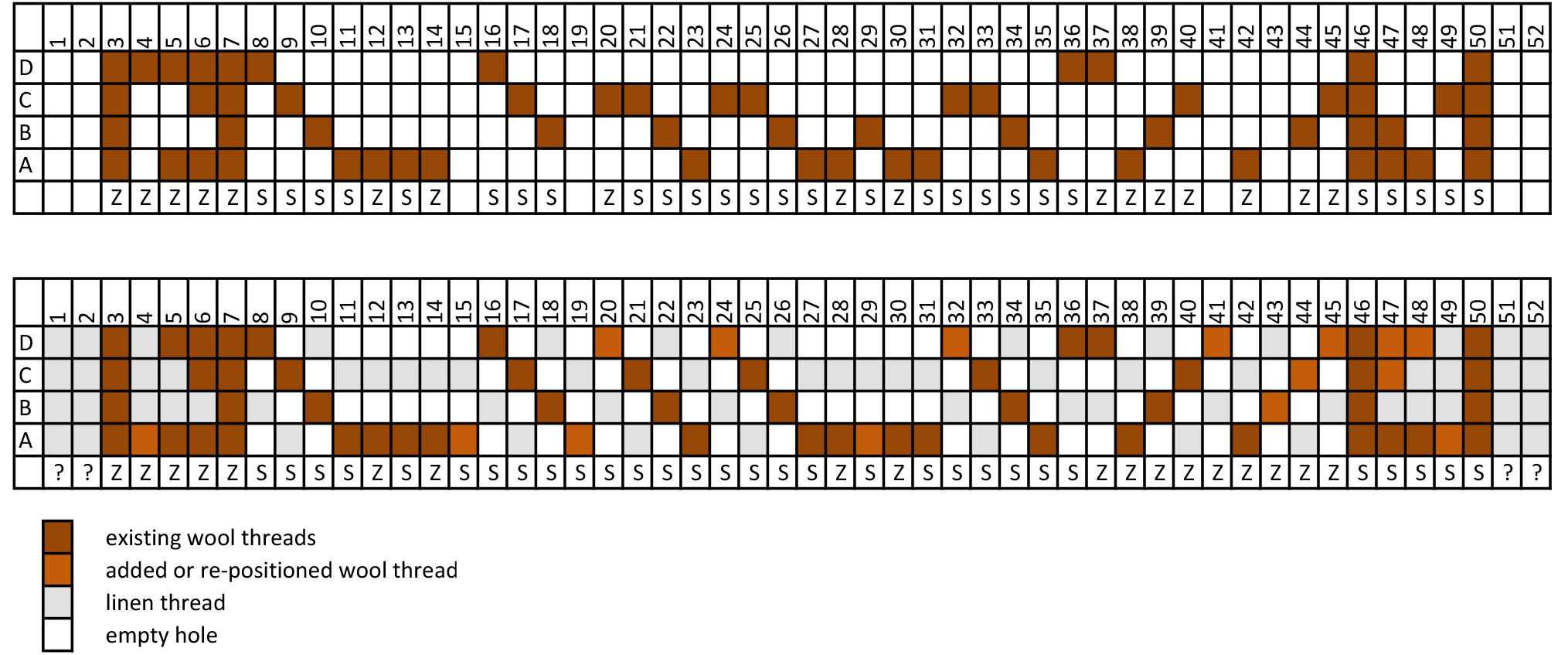

The band was found in the entrance of the tomb threaded with 52 tablets (See Figure 10a). The warp is approximately 4 cm. wide and the woven part is 15 cm long (blue mark in Figure 10b). Today the band is catalogued under number 26E1 together with three other band fragments.

In Figure 10c, crimps on the warp threads are marked in blue as three possible narrow wool lines. At the final part of the band (on the right in Figure 10b) there are hints of crimps but they are not very prominent. It is possible to ascertain that the weaving was stopped in the transition zone between the W-motif and the area where the rectangle with H is located in 13B2. The H in this band has perhaps a wide inner frame made up by single turns3 .

Based on the interpretation of the W motif in Figure 11a, a sketch is made in Figure 11b.

The two outermost tablets on each side (tablet 1 - 2 and 51 - 52) were found without any threads, like in the drawing in Figure 12. Most likely they once have been threaded with four threads in plant material. The warp was described by Gabriel Gustafsson, the excavation leader in 1904, as gathered and tied in six knots (Nockert, 2006, p. 145):

- The edge tablets with 2x7 tablets are gathered in one knot

- The pattern tablets are collected in five knots, one of which is broken

The warp consists of thin brownish wool yarn in the main pattern section with one thread in the tablet and mainly threaded from right to left (S-threaded), some from left to right (Z-threaded). There are impressions in the warp of possibly a plant material. Nockert considered that it might have been in a different colour than natural colour but she did not explain why. The edge tablets (4, 5 and 6 on the left side, and 47, 48 and 49 on the right side) contain one to three light grey wool threads. There are triangular motifs in wool in the selvedge and traces of triangular motifs of plant material. Edge tablets 3, 7, 46 and 50 are each threaded with four threads in a coarser S-twisted dark brown wool yarn: S-twisted cords on the left side and Z on the right side (See Table 2a).

The weft might have been a plant material going throughout the width. The band is brocaded with double threads in red, dark red and one or two bright, possibly white or yellowish colours - all with less twist than in the warp. The motifs with the brocade threads unbound on the back are described as H and E by Nockert (Nockert, 2006, pp. 146-147)4 . The E motifs are paired at an angle to each other and brocaded in light colour in one half and dark red in the other. The two E’s are analogous to the W in this paper.

Table 2a (Above). Preserved threading based on Gustafson’s drawing. Table: Sylvie Odstrčilová.

Table 2b (Below). Probable threading including missing wool and linen threads after corrected position of some tablets. Table: Sylvie Odstrčilová.

The first of the two diagrams (See Table 2a) show the threading of the tablets attached to the unfinished band according to Gustafson’s drawing. For explanation of the symbols ABCD, see Figure 12b. The symbols ABCD refers to the holes in the tablet: Symbol A is close to the weaver on the upper edge of the tablet, B close to the weaver underneath, C furthest away from the weaver underneath and D furthest away from the weaver on the upper edge.

In Table 2b missing threads are added and adjusted in the position of some tablets according to symmetry and analogy to other parts of the pattern. The SZ threading of the tablets in some places indicates that the technique may have been tilting of tablets (turning the tablet around its vertical or horizontal axes) instead of turning in the opposite direction. A V-shape formed by tablets 32-45 was probably part of the W-motif, and the two alternately threaded groups of tablets 11-15 and 27-31 with threads in the same position probably formed the ‘rectangle frame’.

Three other band fragments under catalogue number 26E1

In addition to the unfinished band, three other band fragments are collected under 26E1, all in bad condition. Figures 13a and 13b show the best-preserved parts.

The centre part of the H is slightly damaged but seems to be built up as shown in Figure 13c: a total of ten brocaded rows in each half, brocade over three and two warp threads in the legs and four and five warp threads in the centre part. The inner frame is interpreted as narrow (double turns): with four warp threads in the space between the legs the frame is most likely made up of one tablet/row in wool and two in plant material in the gap between the legs.

27H

27 H was originally a textile cake of a folded part of the tapestry (See Figure 14a). After separation, it turned out that the same tablet woven band was included in the other part (Hougen 2006, pp. 54-56): Figure 14b as the folded side.

The band is measured to be approximately 4 cm. wide, the same as the unfinished band. In 27H the brocade in the H goes over three warp threads and the legs are built up of at least ten brocaded threads or probably 12. The centre part and legs are different than in 26E1 (green marks in Figure 14d): as the open space between the legs is interpreted with five rows/tablets, the inner frame is most likely built up with double turns.

Summary about the motifs in 15A1, 18C, unfinished band, 26E1 and 27H

All reference bands are poorly preserved and even though they show similarities with the band in question, they also show differences in the design (see the summary points below). It was not possible to find an exact analogy, which can be put in place of the unclear spots in 13B2. Analysing the other bands opened more possibilities for interpretation of some of the pattern elements instead of finding the answers for already existing questions:

- Width of the brocade in the W-motif: The width seems to be mostly three tablets, but in the unfinished band the brocade passes over two tablets in some areas and over three in others. The yarn in the bands is thicker as they all are about one cm wider than 13B2 but with same or only a few more tablets.

- The rectangle frame: In 15A1 and 27H the triple diagonals with depressions in-between look like the narrow diagonals in 13B2. In the unfinished band, the wool diagonals look a bit wider than the grooves in between. Their position matches the long sides of the rectangle in 13B2. The short side of the rectangle is visible only in 27H, and it seems to be only two lines like in 13B2. The corners of the rectangle are ‘cut away’ in 27H: in other words, the corners are formed by more than one row. In the tapestry 18C the frame is triple diagonals on both the short and long sides.

- The H: It seems that the H was brocaded over three warp threads in all comparative bands with an H visible. The inner frame in 26E1 and 27H seems to be over one tablet/row using double turns. The design in the ends of the legs and the centre part of the H in 26E1 seems to be different from the other bands. The centre part in 27H looks more like 13B2, with five brocade stitches.

- The dots: Dots are visible only in 27 H and the tapestry 18C. It seems, however, that they touch the frame of the rectangle with only a narrow groove (missing plant material). The width of the frame around the dot cannot be determined from the photo of 27H, but because the inner frame is most likely made up of one row/tablet the frame around the dots is probably the same. If dots had been visible in 26E1 they should also most likely be one tablet/row.

Experiments and results

As mentioned earlier the intention of the experiments is to develop a design that can meet the assumption of what is the most likely rectangle motif for 13B2: a design based on corners made up of a maximum of three rows. In addition to the restrictions that the corners of the rectangle adjacent to the selvedge consist of one to a maximum of three rows, it must also fit in with a set of criteria based on the analysis of the material in the previous section. Patterns with two rows in the corner made the motifs inside the frame asymmetrical and did not fit with the requirements.

In the final experiments, handspun wool (spun on a drop spindle as the wheel did not exist in the Viking Age) from Wild Norse Sheep is used. The warp yarn is natural dark grey in approximately 28/2 in a hard twist. Yarn for the brocade is in the same wool quality, approximately 20/2, but in loose twist and plant dyed in dark red, red, orange, light brown and yellow. Two-ply linen in 35/2 is used in the warp and 30/1 in the weft.

Rectangles with one and three rows in the outer corners

The rectangle design that ends in a sharp point in the outer corners (one row) allows for perfect symmetry and a harmonious aesthetic where all lines that surround the motifs outside and inside are made with narrow lines in wool. This is a probable understanding as two of the best preserved H’s (26E1 and 27H) have previously been interpreted with an inner narrow frame in wool made with double turns. It is only the inside grooves surrounding the dot and the ‘gap’ into the H that are made up of two linen lines.

The brocaded H is built up of ten stitches in each half and with five stitches in the center. The ends of the legs in the H (See Figure 15a and 15b) are in this design with brocade over only one warp thread and can perhaps be considered as an aesthetic flaw. The way the legs end gives a slightly blunt expression in contrast to how they are rounded in a nicer way in both 26E1 and 27H.

The rectangle with three rows/picks in the outer corner has a harmonious aesthetic design. The dots at both ends of the rectangle are closer to the short sides with a narrower frame. The inner frame in the H is wider with single turns and the ends of the legs are with double turns.

All the criteria are met in these two test versions, except that the outer corners with one row (See Figure 16a and 16b) does not look like the original band. On the other hand, the corner with three rows looks the same as in the original (See Figure 16c and Figure 16d). During the weaving, it was discovered that by changing the direction of turn in the right place, the corner would be more pointed as in the original in Figure 17a - and in the test in the upper right corner in Figure 16b.

The rectangle designed with outer corners that lead out in three rows can be described as a strong similarity to the original. As I earlier described ‘tilting the tablets’ (in the unfinished band in Table 3a) it is possible that the weaver used this technique instead of changing the direction of turning the tablets as I prefer.

How to weave 13B2

In my patterns I use the term positions for the ABCD-holes in the tablet: then position A means that the relevant thread / colour should be at the top and closest to the weaver (see Figure 12b).

I use the S and Z symbols in the threading diagram for threading direction (see Figure 17d):

- S-threaded tablets are threaded from right to left. When turning the tablets forward, the stitches in the band will be tilted to the left and marked as: \

- Z-threaded tablets are threaded from left to the right. When turning the tablets forward, the stitches in the band will be tilted to the right and marked as: /

Threading: In this pattern, all the tablets in the pattern part are threaded Z.

Turning: Turning symbols are:

- For a quarter turn: \ or /

- For a half turn: \\ or //

- Some places the tablet must stand still (not marked)

Empty holes: I do not mark empty holes in my patterns as threads in the A and D positions are floating. I only mark the setting of tablets in Row 0 with an O meaning empty hole – to make the start correct.

Row 0: Setting of the tablets:

- A for A-position and D for D-position

- O for empty holes

Conclusion

The experiments with drawing and weaving motifs and techniques of poorly preserved parts of 13B2 have resulted in a probable interpretation of how the rectangle section can be reconstructed. Based on detailed descriptions and analysis of the material, criteria were developed as a framework for experiments. Old photographs of four similar bands have helped to gain a greater understanding of weaving techniques and design of motifs, as those photographs were taken 100 years ago when the fragments where in much better condition than today. There is painstaking work behind the development of criteria as a framework for experiments which ended up with two relevant constructions for testing. Comparing the poorly preserved parts in 13B2 with corresponding parts in the other four bands, the result can be said to be a probable reconstruction with an authentic aesthetic expression as in the original. The total of six colours chosen on the wool yarn in the reconstruction can only be said to be possible, but there may also have been fewer colours as it may look like in some of the other bands used for comparative studies.

In my very first interpretation of 13B2 (Skogsaas, 2020) a weaving technique is used where all the motifs are woven with two turns of the tablets. In this new interpretation, both techniques are used: 1) one turning of the tablets in the W motif and the two small motifs above and below and 2) two turns in the rectangle itself, but one turning in the inner parts of the H and the dots. This has given the weaver room to use the same motifs in bands with more or fewer tablets: making narrower or wider bands. Ending up with techniques like in this band: sections with one turn and sections with two turns, is rather unusual to find in historical bands in general.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Sylvie Odstrčilová for discovering something I had overlooked and for fruitful discussions about motifs and techniques in 13B2. Then I am grateful to Shelagh Lewins for her proofreading of the script.

- 1The original band is photographed in two parts. The whole tapestry fragment can be seen in Figure 2.

- 2A reconstruction of this decorative textile is made by Marie Wallenberg and an article is forthcomming.

- 3An article on a further interpretation of the unfinished band is being prepared by Sylvie Odstrčilová.

- 4As we cannot see any unambiguous H motifs in the unfinished band, neither in old photos nor during new photography in 2021, it is possible that Nockert refers to the other bands under catalogue number 26E1.

Keywords

Country

- Norway

Bibliography

Collingwood, P., 2015. The Techniques of Tablet Weaving. Northampton: Echo Point Books & Media.

Holmqvist, V., 2010. The Use of Craft Skills in Historical Textile Research: Some Examples Drawn from a Study of Medieval Tablet Weaving, in: H. Hopkins, ed. Ancient Textiles, Modern Science. Re-creating Techniques through Experiment. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 49 - 63.

Hougen, B., 2006. Billedvev, in A.E. Christensen and M. Nockert, eds. 2006. Osebergfunnet. Bind IV Tekstilene. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, UiO, pp. 15-140.

Ingstad, A. S., 2006. Brukstekstilene, in A.E. Christensen and M. Nockert, eds. Osebergfunnet. Bind IV Tekstilene. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, UiO, pp. 186 - 276.

Nockert, M., 2006. Brikvev och brikband, in: A.E. Christensen and M. Nockert ed., 2006. Osebergfunnet. Bind IV Tekstilene. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, UiO, pp. 141 – 160.

Lammers-Keijsers, Y. M. J., 2005. Scientific experiments: a possibility? Presenting a general cyclical script for experiments in archaeology EuroREA 2/2005, pp. 18-25.

Raeder Knudsen, L. and Grömer, K., 2011. Discovery of a new tablet weaving technique from the Iron Age Archaeological Textiles Review 54, pp. 92-97.

Raeder Knudsen, L., 2014a. Teknologihistorisk analyse af brikkevevning fra ældre jernalder. Doktorgradsavhandling, København: Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademis Skoler for Arkitektur, Design og Konservering.

Raeder Knudsen, L., 2014b. Tacit Knowledge and the Interpretation of Archaeological Tablet-Woven Textiles, in: S. Bergerbrant and S.H. Fossøy eds.,2014. A Stitch in Time: Essays in Honour of Lise Bender Jørgensen. Gothenburg: Gothenburg University, pp. 91-110.

Rosenquist, A. M., 2006. Analyser av Osebergtekstilene, in: A.E Christensen and M. Nockert ed., 2006. Osebergfunnet. Bind IV Tekstilene. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, UiO, pp. 170 – 184.

Skogsaas, B., 2019a. Rekonstruksjon av Oseberg 34D. Mastergradsavhandling. Universitetet i Sørøst-Norge: Fakultet for humaniora, idretts- og utdanningsvitenskap, Institutt for Tradisjonskunst.

Skogsaas, B., 2019b. Oseberg 34D. Reconstruction and weaving step by step, Oslo: Kolofon Forlag A/S.

Skogsaas, B., 2020. Oseberg. 9 Tablet woven bands, Oslo: Kolofon Forlag A/S.

Det store norske leksikon. Available at: < runer – Store norske leksikon (snl.no) > [Accessed 8 June 2022].