The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

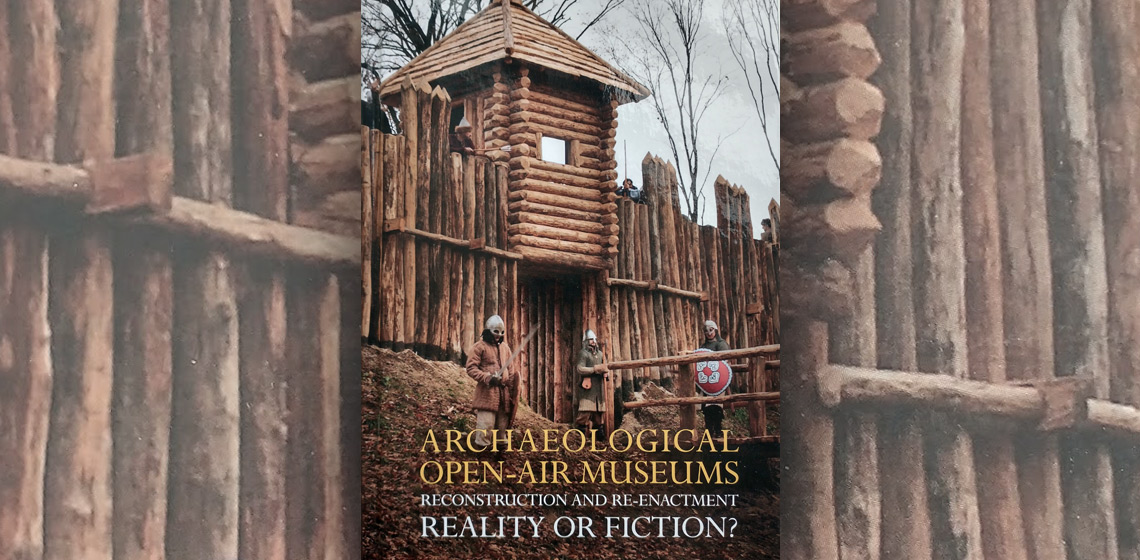

Book Review: Reality or Fiction?

In October 2018, a conference took place in Southern Poland. It was attended mainly by people from Poland and Slovakia, but also included several EXARC members from abroad. The conference was titled “Archaeological Open-Air Museums: Reconstruction and Reenactment – Reality or Fiction?” which is also the title of this book which was published in 2022. The conference was the result of a cooperative project between Poland and Slovakia and took place at the Carpathian Troy Archaeological Open-air Museum near Krosno, Poland. The conference was reviewed in the EXARC Journal here: https://exarc.net/issue-2019-3/mm/conference-review-trzcinica-2018

The book consists of 462 pages; all 13 articles are in English with a summary in Polish. Some papers are purely archaeological and have nothing to do with museums or reconstruction, for example Valde-Nowak’s paper on “The Stone Age at the foot of the Tatra Mountains – Oblawoza Archaeological Park” and Tunia’s which touches on the history, state of preservation, contemporary presentations and form of protection of megalithic tombs from the Neolithic period.

Pelillo and Zanasi gave a presentation on Parco Montale near Modena, Italy. Similarly to a part of the Carpathian Troy Archaeological Open-air Museum, although the museums vary from each other, Parco Montale is also inspired by the Bronze Age. The Italian delegates discuss whether archaeological discourse should be evocative or educational. What if you involve schoolchildren in how archaeologists work so they better understand ancient technological and cultural processes? Pelillo and Zanasi also support the use of ancient technology, which often better describes activities undertaken in open-air museums as opposed to experimental archaeology. The latter phrase is used too often. The article is a good reflection on the developments at Parco Montale over several decades against an international background.

Zyzman & Kunicka-Zyzman give a short account of a reconstructed Bronze Age settlement near Kraków, originally built by an association, but transferred in 2011 into the hands of the Museum of the AGH University of Science and Technology and rebuilt in 2018.

Kotorová-Jenčová then presents an overview over the Archaeological Park Live Archaeology in Hanušovce nad Topľou (Slovakia) as a place of experiment, cognition and fun. This park has been open since 2013 and was built partly with support from the European Union, allowing visitors to experience daily life in the reanimated past, as she puts it. This park’s merits are the activities, for which the objects used are just tools. Kotorová-Jenčová emphasises the need for a vision: it is not enough to produce a park and keep it running, there needs to be ambition. She mentions how archaeological open-air museums deliver a hands-on context to archaeological artefacts, which showcase museums cannot live up to.

In some ways, what is presented at archaeological open-air museums is always fictitious. However Kotorová-Jenčová argues that these sites are of great use. This article is a very pleasant contribution which does not only look at a case study, but then progresses to wider deliberations and conclusions.

Gancarski & Madej, the hosts of the conference, continue with explanations as to why they constructed their archaeological open-air museum “Carpathian Troy” in Trzcinica, Poland. It has the advantage of being a site museum; the magic of being the genius loci is apparent. The idea of creating this large open-air museum dates to 1998 and followed excavations. The site opened in 2011.

Przychodni is based in central Poland and has a long history of presenting archaeology to the public, and experimental archaeology. He aptly titled his presentation “The show must go on. Subjective reflections on the reconstruction of everyday life of ancient iron smelters in the Świętokrzyskie region, Central Poland.”

He starts by rectifying some parts of the history of metallurgical research in the region which probably started in the interbellum. The first iron smelting festivals took place here in the 1960s, going by the name “Dymarki Świętokrzyskie”. The annual festival was quite something in the context of communist Poland but had only limited archaeological content. Przychodni mentions how the festival has changed a lot over the decades, but that for many people involved over the years there was a “the show must go on” mindset, and a year without the festival was not an option. The image of the past as presented at this festival is very much based on a generic romantic depiction of this region. It is a tourist feast without much depth, and this hasn’t improved over the years.

Both the presentation by Baginska & Woloszyn (Cherven’ Towns in the public space: state and perspectives) and by Hupalo & Voitsehschuk from Ukraine (Ancient Zvenyhorod historical and cultural reserve: research and promotion of the forgotten princely capital) have been added to this book as bonus material. Both articles describe plans for future (open-air) museums.

Byszewska-Łasińska is from the National Heritage Board of Poland and discussed “the image of the past. Standards of reconstruction and presentation of archaeological heritage from the perspective of archaeological heritage management.” She starts with definitions of cultural heritage and its features, which is more of a mine field than one would expect. It is not just about economical and functional potential of (archaeological) sites just to mention something. Expectations differ, discussions are lacking, and this leads to conflicts between parties with different agendas. If we then move onto tourism and phrases like “archaeological reserve” it even gets more complicated. Byszewska-Łasińska refers extensively, and rightly so, to the International Charter for the Protection and Management of Archaeological Heritage, Lausanne 1990, for example with the simple phrase: “Reconstructions serve two important functions: experimental research and interpretation.” If this article makes anything clear, it is how complicated it is to set or follow standards if people do not use similar definitions. There are, however, plenty examples where it works out very well.

Baraniecka-Olszewska then investigates historical re-enactment as an authentic practice which, in her words, is neither reality nor fiction. She observes the re-enactment world as an anthropologist. In her perspective, the division between reality or fiction is blurred as re-enactment is very much about social reality suspended between different worlds. In this sense, the struggle for authenticity in re-enactment is real, even if authenticity itself is relative and not absolute. Imperfections will always remain. The material and mental sphere of the past can be at best approached, but never quite reached. Archaeologists can be pessimist and abandon re-enactment, while many others would state it is better to try to approach the past this way than not approaching it at all. There is always a slight feeling of discomfort involved, leading to new questions. Baraniecka-Olszewska then dives deeper into object authenticity and existential authenticity, based on historical knowledge and imagination.

Two articles conclude these proceedings: Lityńska-Zając & Mueller-Bieniek on archaeobotany as a source of information on old economics and landscape, and Moskal-del Hoyo & Lityńska-Zając: “wood resource use – tracking prehistoric human activity and reconstructing woodland vegetation. Case study of the Carpathian Troy archaeological open-air museum in Trzcinica (South Poland)”. Simply said, “the world cannot be described without the knowledge of the local flora” (Olga Tokarczuk, 2022, Czuły narrator, 197). With this conclusion a solid archaeological base is given to some of the primary work of archaeological open-air museums.

For me, the most valuable articles here are by Kotorová-Jenčová, Byszewska-Łasińska and Baraniecka-Olszewska. The other articles are good background reading for those who would like to better understand the debate in this part of Europe. As this was the second conference of its kind at this museum, we can hopefully look forward to another conference in a couple of years.

Book information

Jan Gancarski, editor, 2022. Archaeological Open-Air Museums: Reconstruction and Reenactment – Reality or Fiction?, Krosno: Muzeum Podkarpackie w Krośnie, ISBN: 978-83-963219-2-3, 462 pp.

Available through the museum only (https://muzeum.krosno.pl/produkt/archaeological-open-air-museums-reconstructions-and-re-enactment-reality-or-fiction/), costs: 112 PLN.

Keywords

Country

- Poland