The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

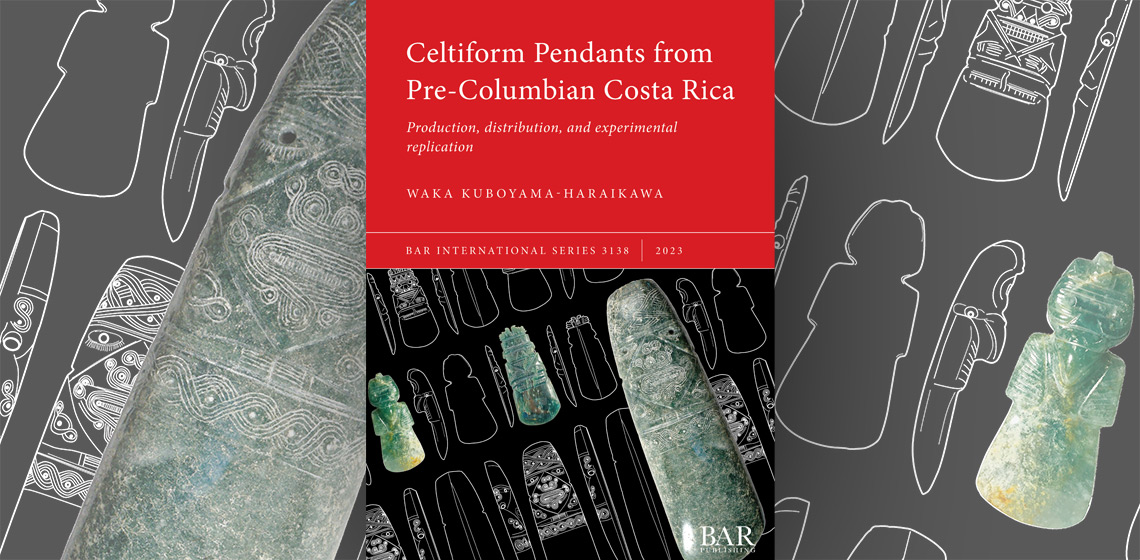

Book Review: Celtiform Pendants of Pre-Columbian Costa Rica: Production, distribution, and experimental replication by Waka Kuboyama-Haraikawa

In her book, Celtiform Pendants of Pre-Columbian Costa Rica: Production, distribution, and experimental replication, Waka Kuboyama-Haraikawa seeks to highlight lapidary technologies in Costa Rica by examining the social application and production of celtiform pendants. Haraikawa is a PhD research fellow for the Center for Northeast Asian Studies at Tokyo University. Ms. Haraikawa’s research includes studies on pre-Columbian lapidary manufacturing with a focus on jade artifacts. Her work encompasses the chain of production, technologies, material analysis, utility, and distribution of jade pendants specifically within Costa Rica. Haraikawa has published several papers that examine technological applications in lapidary contexts throughout pre-Columbian Costa Rica.

In her observation of the Formative to Terminal periods (2000 BC to 1503 AD), Haraikawa considers significant evolution in manufacturing by assessing stable societal formation through evidence of perishable buildings, ceramic complexes, and local agricultural production. She postulates that the geographical landscape surrounding Costa Rica led to increased mobility of raw materials and technological and social influences. This study makes a connection between an increase in jade artifacts and lapidary practices and the establishment of elite-controlled societies within Costa Rica, Mesoamerica, and parts of Mexico. It may also be observed that an increase in lapidary production accompanied an increase in agriculture, specifically maize. The design and selection of certain motifs, the hardness of the raw material, and the application of technology suggest that celtiform pendants were items of prestige.

Through assessing the utility of celtiform pendants in Costa Rica, Haraikawa hopes to present a better understanding of pre-Columbian societal behaviors as it relates to objects of prestige. Since jade artifacts were more prevalent between 500 BC and 900 AD, special consideration was given to technological approaches and distribution patterns within Costa Rica and the surrounding regions during this period.

Though it is clear that societies evolved into more stable productive centers with the movement of goods, skills, and technologies, it is not entirely clear how materials were garnered and ideas shared. It is also unclear what exactly gave rise to the elites or at least how they exercised control over those materials that would then be manufactured into such prestigious objects as celtiform pendants.

It has been observed that many pendants have been uncovered in Mesoamerica in ritual contexts, while some have been recovered from archaeological sites in Mexico and Costa Rica, the majority of which were funerary contexts. Larger volumes of pendants were recovered from the Greater Nicoya and Caribbean regions. Many of these burials contained items other than jade pendants which would lead to an assumption of status.

Haraikawa did make mention of possible sites for the acquisition of raw materials in areas surrounding Guatemala. Her recorded distribution of jade pendants makes this quite plausible since pendants were found both north and south of the area. The exchange of ideas and material technology is not especially clear but may be indicated by the choice of pendant motif and the centrality of raw jade materials. The operational sequence of the pendants seems to expand not only over extended periods of time but also over great distances and can be seen in some of the incomplete and re-purposed pendants. Haraikawa suggests that some of the unfinished work may be connected with elitists who finished the work themselves or at least determined how the work was to be finished. This reader fails to see the elite connection at any point of acquisition, manufacture, or distribution.

Haraikawa’s experimentation did highlight the tedious and time-consuming process of celtiform pendant formation. Her traceological analyses were consistent with her approach to pendant formation with the tools and materials used during the experimentation. There seemed to be quite a bit of influence from the Olmec people and some from the Mayan tribes. However, Costa Rican influence did not seem to be as prevalent in the formation of celtiform pendants.

Haraikawa has done a great job of examining some possible techniques and similar shared artistic ideas within the regions between Mesoamerica and Costa Rica. These ideas are highlighted in the morphology of the pendants found at the recorded archeological sites and those housed in the Jade and National Museums of Costa Rica. The significance of jade artifacts and celtiform pendants is obvious as related by their contexts in religious and funerary settings. Fluid movement of ideas, trends, and materials may be observed in cultures throughout Mesoamerica and Costa Rica as evidenced by agriculture, housing, and manufacturing centers. It is clear that celtiform pendants were items of prestige if for no other reason than the time it takes to produce even one pendant. However, it is still rather difficult to make the connection between these prestigious items and human behavior during the pre-Columbian era, specifically during the time when jade lapidaries seem to have flourished.

Haraikawa’s book, Celtiform Pendants from Pre-Columbian Costa Rica: Production, distribution, and experimental replication was an enjoyable and informative read for a biblical field archaeologist who has no connection with Central or Latin America. Like any good archaeologist, Haraikawa knows her specialty, how it can be improved, and where study should go from here. This publication is a work well written.

Book information:

Waka Kuboyama-Haraikawa. 2023. Celtiform Pendants from Pre-Columbian Costa Rica. Production, distribution, and experimental replication. BAR Publishing, BAR number: S3138

ISBN: 9781407314969 Paperback: 168 pages

Keywords

Country

- Costa Rica