The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

RETOLD: CIDOC CRM and the Documentation of Buildings and Crafts

Cultural heritage documentation is the process of systematically recording and preserving information about historical artifacts, monuments, traditions, and other intangible cultural expressions. One of the primary aims of the RETOLD project was to create a prototype for immersive digital storytelling that communicates cultural information to diverse audiences, museum professionals and museum workers in an understandable and engaging way. We aimed to co-design with the museum partners a piece of technology that would address the most pressing aspects of digital storytelling relevant to open-air museums.

Introduction

During the first phase of the RETOLD project, we found that one of the biggest challenges in open-air museums is collecting data digitally in a structured manner, which would allow the data to remain available for retrieval and future use in digital storytelling projects. This task was much more urgent and important to museums than creating immersive experiences for example a digital experience like virtual or augmented reality.

For the RETOLD project, this meant that we needed to help museums: 1. Preserve the tangible and intangible knowledge within their organisations. 2. Organise this digital material in a way that could facilitate future storytelling and enable museums to proceed with digitalisation.

To achieve these objectives, the museum partners explored and received training in the building blocks of immersive storytelling - audiovisual media and 3D capture. The RETOLD consortium designed a digital data collection interface that would help partners to interactively test the collection process and the categories within the necessary data collection forms.

NUWA as the creative technology partner conducted user research, consulted on development of web applications, helped align the data structures of the prototypes within the requirements of the museums, and trained museum staff in creating the building blocks for immersive content, such as 3D models and photogrammetry and digitising archive material and video documentation.

Open-air Museum Data Meets Software: Aligning Cultural Heritage Data with Linked Data Models

For the data collection prototype, the goal was to establish a basic web application framework that could demonstrate the feasibility of the concept. NUWA and developers at UAB first concentrated on gathering user requirements to design early architecture, user interface, and initial feature sets, ensuring alignment towards ease of use for museum staff and volunteers.

UAB implemented a lightweight, back-end architecture within raw PHP, allowing early testing of interactions between the backend with the front-end modules. In tandem, the first UX/UI framework was designed, catering to users with varying levels of digital proficiency in museums and other cultural institutions.

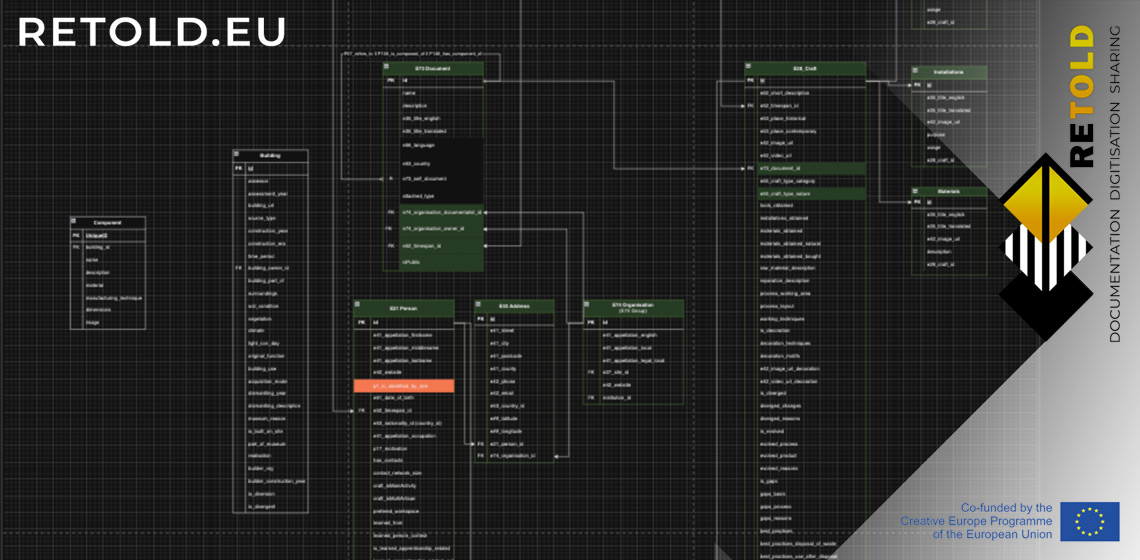

As we moved to TRL5 (Technology Readiness Level 5), the Proof of Concept stage, the emphasis shifted to work towards a more expansive set of features and the implementation of the 460 discovered data points in a data model that followed CIDOC’s Conceptual Reference Model for the back-end. This phase was much more intense in terms of both semantic analysis, relational system logic and performance.

The design of the back-end was extended as far as possible to accommodate real-time data processing, more complex queries, and increased changes in the cultural heritage dataset. The most critical part of this phase was ensuring that RETOLD’s data model adhered to the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) (ISO 21127). Being a standard for integrating, managing, and sharing cultural heritage information, CIDOC was selected at the beginning of the project as the essential framework for ensuring semantic consistency and interoperability across diverse datasets.

We dedicated significant time to researching, analysing and designing a backend that could align with this model and the continuous changes in the data collection forms which were still iterated on.

The data architecture that would, in the end, become the enabling solution for seamless integration of diverse cultural heritage assets, was meant to foster accurate digital storytelling and preserve the context of every recorded craft and/or building.

The execution of this complex task involved conducting twice-weekly developer meetings to discuss product development, continuous iterations of the original data model to align with a semantic model in SQL, and maintaining close alignment with the requirement specifications through regular work sessions with UX experts, coordinators, and sectoral professionals. This fast paced methodology focussed on the urgent integration of user interface updates and maintenance of the integrity of the requested development roadmap.

From a technological perspective, the use of a semantic model such as the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) (ISO 21127) is essential for supporting digital storytelling in cultural heritage.

Storytelling within this domain often involves intricate relationships between people, objects, events, and places —data that needs to be organised in a way that both preserves these relationships but also makes them easily navigable by users and computers. Semantic modelling enables this by offering a structured way to capture, transform and represent data, facilitating interoperability between organisations and diverse systems and datasets.

CIDOC’s Conceptual Reference Model, as a reference for advanced linked data or semantic model, provides a standardised framework for linking cultural heritage data, ensuring that museums, archives, and other institutions can share and integrate information seamlessly and make their records findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable by researchers, audiences and enthusiasts across the globe.

Process and Challenges

The 460 data points identified through the design of documentation forms were initially separated into the categories of crafts and buildings. In a second stage those were then segmented in a large spreadsheet in relevant subsegments i.e. temporal, geographic, material-based and other attributes part of the v7.2.0 of CIDOC’s Conceptual Reference Model Entities. This approach and the extracted taxonomy facilitated the collaborative work to unearth the linked data relationships between each and every segment, sub-segment and individual datapoint, so as to ensure a modellable standard completing the primary aim and so that cultural and architectural contexts were consistently maintained in the foundations of a storytelling model.

The primary challenges of the process revolved around maintaining a cohesive vision while coordinating with diverse stakeholders who had varying levels of expertise in technology. Managing communication and expectations across multiple teams proved complex, given the advanced new technological context of Web3 Linked Data.

We aimed to overcome these challenges by implementing a more structured communication strategy, recurrent meetings and reporting closely aligned with agile methodologies and the scrum development cycles, ad RASCI responsibility matrix that included regular alignment calls and feedback loops. These were meant to help stakeholders understand both the project vision and the underlying technologies. In cases where technological expertise was lacking, we adapted their roles through collaborative adjustments to ensure continued progress.

For consortia embarking on a complex cross-disciplinary project such as RETOLD, the following collaborative principles are highly recommended:

- Early stakeholder capacity assessments to define roles appropriately and facilitate mutual understanding.

- Articulate and communicate a clear, realistic and cohesive vision to ensure focus and avoid scope creep.

- Implement consortium centric standardised decision-making processes to align cultural heritage stakeholders, designers and developers.

Prioritising Usability over Interoperability

In February 2024 the team discussed the priorities of developing the data collection system, in particular the importance of interoperability. Given the time constraints of the project timeline, it was not possible to meet both the UX requirements and the objectives of creating a CIDOC-conforming data structure at the same time. As a team, we saw that if the data collection tool was not easy to use, museums would not adopt it, and there would be no data to work with at all. CIDOC-CRM compliance was an ambitious requirement, and a tool based on a simpler model, such as EDM, could be a better way for Open-air museums to get started with digital data collection.

The main priority for the project remained: Enabling Open-air museums to capture the multimodal data and forms of knowledge present in their organisations in a way that would make it accessible and shareable. Since the data collection forms for buildings and crafts were still in progress, aligning the data to a particular model was not practical at this time. However, the alignment exercise yielded valuable insights in how complex and substantial the connections were between the data that Open-air museums in particular would want to collect. In particular activities such as craft skills and experiments were not only location-bound, or defined by time periods, they might also be ongoing into the future, with multiple changing actors and entities involved, making the linked data structure potentially infinitely more complex than in a collection-based museum. In turn, the subsequent integration between the data structure and a user-friendly interface proved extremely challenging.

As project evaluator Lukas Staeding mentions in his report, “In the case of RETOLD, challenges lie particularly in the connection between material cultural assets (buildings) with intangible cultural assets(craft techniques). It is precisely the ephemeral character of immaterial knowledge that requires this special care in documentation. Unfortunately, international standards were developed primarily with a focus on physical objects such as art and cultural objects, which makes orientation difficult.”

Impact on Project Outputs

Due to the inherent difficulties in data management in a sector so rich with intangible heritage, we took encouragement from the interim reports and experts’ guidance to make the strategic decision to simplify the application back-end to a traditional data storage utilising Drupal as a basic Content Management System (CMS). This way we could make sure that museums were still able to capture data and store the audiovisual and 3D media they had been creating during the project. Since our main priority was data capture and digitisation, this compromise allowed us to learn about the intricacies of linked data models and their relationship to Open-air museums, while still meeting the primary project goals.

We also found that it would be efficient to use the current project partners’ experience in managing their data as a base for further exploration on linked data models relevant to Open-air museums after the conclusion of RETOLD, rather than releasing the digital tool to the public. As more users would collect data in a roughly structured manner, it would be more difficult later to organise this data within a specific data structure.

Finally, our preparatory work on relational data and linked data model analysis will form the basis of further study into the integration of time-based data in open-air museums within an ISO 21127 certified or CIDOC-compliant model.

Despite the apparent set-backs in our discovery of linked data models, Dr Staeding’s evaluation points out “[...] already fills a gap within the museum documentation landscape by not focusing on physical objects (paintings, vases, etc.), but is dedicated to the immaterial knowledge of crafts. Here the project not only provides impulses for the conception of such a recording practice, but also provides partners with a practical application.”

Through committing to the exploration of both creative technologies and rigorous data collection approaches, we aim to build on these initial impulses and support Open-air museums in their quest to digitally capture and share tangible and intangible heritage to their audiences.

Keywords

Bibliography

Meijers, E., and Isaac, A., 2019. Aggregation of Linked Data in the Cultural Heritage Domain: A Case Study in the Europeana Network. Information, 10(8), p.252. MDPI

Simou, N., Chortaras, A., Stamou, G., and Kollias, S., 2018. Enriching and Publishing Cultural Heritage as Linked Open Data. SpringerLink: Springer.

Kabassi, K., 2021. Special Issue: Linked Data for Cultural Heritage. Information, MDPI.

Gonçalves, A. O., and Miran, M. S., 2021. Digital Archives as Linked Open Data: A Cultural Heritage Perspective. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 36(Supplement 2), ii155-ii168. OUP

Europeana Data Model Primer. (2019). Europeana Professional. Europeana

Bizer, C., Heath, T., & Berners-Lee, T., 2019. Linked Data: The Story So Far. Semantic Services, Interoperability and Web Applications.

Europeana Foundation. 2020. The Europeana Data Model: A Foundation for Cultural Heritage Aggregation. Europeana Professional.

Clarke, M., & Harley, P,. 2021. Semantic Enrichment in Cultural Heritage: Using Linked Data to Improve User Experience. Science Editor.