The content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License.

Reviewed Article:

Black Ash - a Forgotten Domestication Trait in Garden Orach (Atriplex hortensis L.)

Garden Orach (Atriplex hortensis L.) is a vegetable plant of minor importance but with a wide distribution throughout the Old World and beyond. Previous research revealed its diverse medicinal and magical importance in prehistory. Here, Orach’s special ability to retain sodium even in non-saline ground is introduced. The outstandingly high concentrations of sodium in dry plant matter and plant ash suggest its use as a salt substitute, manifested in an early domestication trait. Special attention is paid to the variability of this trait in cultivars from different geographic regions and within the genus Atriplex. Besides analytical data, several practical experiments to obtain and use Orach salt were carried out. Plant ash was applied to preserve cheese and ferment food with promising results. Refined salt was extracted from the ash using simple rural methods.

Background

Salt - sodium chloride (NaCl)- if available, is consumed by herbivore mammals as well as humans in amounts way above its physiological necessity (Henney et al., 2010). Craving salt is driven by its specific taste as well as its ability to improve the taste of many other foodstuffs (Mc Caughy and Scott, 1998; Breslin and Beauchamp, 1995). The physiological and evolutionary mechanisms of this specific hunger are at least partially understood. Even though salt does not leave traces in archaeological excavations, it is believed to have been valued even by Paleolithic man. And salt, besides the sensual effects, is able to prepare and store food. Furthermore, it controls osmoregulation and neuronal communication and is considered effective in preventing malnutrition in low-protein diets (Henney, et al,. 2010, Venable, et al., 2020).

Sodium is the sixth most abundant element in earth's crust but with an uneven distribution (Kronzucker, et al., 2013). The abundance of sea salt contrasts to the lack of salt in most terrestrial environments. There, precipitation immediately dissolves salt into lower ground layers. Only inland salt marshes and underground mining may provide access to salt for inland communities. Thus, the migration of early man along the seashores coincides with availability of salt, which had to be compensated by those inhabiting inland territory. Even in Greek and early Roman times several European barbarian people without the knowledge of mined salt and sea salt were described in literature as living north and east of the Alps (Hehn, 1919, p. 18). The coastal advantage vanished with the rise of large-scale salt mining and extensive trade beginning as early as for the European Bronze Age (Saile, 2012; Stöllner, 2007).

In addition to the brine of seawater or inland salt marshes, there is a long tradition of PAS use in several parts of the world. Ash from purposeful combustion is considered a salt substitute of highly varying quality and taste, depending mainly on plant species. A wide sodium-potassium ratio with low concentrations of sodium is characteristic for the plant kingdom, whereas this ratio in animals and humans is significantly narrowed (Lueger, 1904, p. 306). Modern health care and physiology argue for a low-sodium diet to reduce negative effects of excessive intake. The physiological effects of excessive consumption are of greater interest in current research than basic strategies to secure the minimum intake of sodium in absence of crystaline salt. However, a deficiency scenario must have challenged many prehistoric communities (Phanice, 2016; Kronzucker et al., 2013, Henney et al., 2010).

Not all salts containing sodium taste salty in the way sodium chloride does. Potassium might substitute sodium in taste and preserving ability at least to some extent (Breslin and Beauchamp, 1995; Mc Caughy and Scott, 1998). The highest alkaline concentrations were found in plants growing on saline ground (Calone et al., 2021). But the need of PAS practice certainly grew with the distance to such habitats. Today, only regions cut off from salt trade or those with persisting spiritual and ritual connections still maintain PAS practice (Okoli, 2023). Recent documentation covers tropical regions such as Papua New Guinea, most of sub-Saharan Africa, the Amazon basin and the Paraguayan Chaco. PAS practice is considered a fundamental human knowledge by most of the involved indigenous communities themselves and is found embedded in elaborate spiritual and ritual concepts (Cozzo, 2024; AISD, 2024; Echeverri and Enokakuiodo, 2013; Schmeda-Hirschmann, 1994). It is associated with initiation ceremonies, with ritual gifts or in preparing specific indigenous food (Okoli, 2023, Gopalakrishnan, 2015; Cozzo, 2024; Echeverri and Enokakiuodo, 2013). Papua New Guinea's PAS technology is ethnobotanically well-documented and makes use of ashes from over 30 species (Ryutaro et al,. 1987). A plant ash consumption without refining procedures is documented for parts of Africa and for Papua New Guinea, emphasizing ashes of dark or black colour (Gopalakrishnan, 2015).

In the Paraguayan Chaco, the indigenous word for ash is congruent with the name of the plant used in PAS tradition (Schmeda-Hirschmann ,1994). The common ground of ethnobotanical and cultural data on PAS practice from different parts of the world gives rise to the idea of an ancient technology with a formerly widespread distribution.

Only scarce records of plant ash use are available from European history. The ash of several halophytes (saltworts) from the Mediterranean and Atlantic shores, known as barilla, was extensively traded and used in glass making and soap production from medieval times onwards (Ortuño et al. 2021). Most of these coastal saltworts such as Kali turgidum (Dumort.) Gutermann, Salsola soda (L.) Fr., Salicornia europaea L., Atriplex halimus L. and others are found within the families Chenopodiaceae or Amaranthaceae. Dietary use of PAS from any of those plants is not recorded in European history. Sometimes wooden ash was used as a conserving medium, such as in 18th century French Morbier Cheese (Syndicat Interprofessionel Morbier, 2025). But these sporadic cases were not intended to substitute ordinary salt.

Garden Orach is a domesticate with documented cultivation from Western China, India and Nepal throughout all of Eurasia and parts of North Africa (powo, 2024), but in most regions people gave up its cultivation and use. Whether in contemporary Ladakh (North India), in Greece of the classical period or in 16th century Central Europe the leaves of the plant were excessively used in cooking and as salad (See Figure 1). The red varieties preceded the green ones (Zwiebel, 2024). Several such leafy vegetables served for the same purpose as Sorrel (Rumex spec.), Goosefoot (Chenopodium spec.) or Mallows (Malva verticillata L.) and were often combined in dishes. Only the introduction of Spinach (Spinacea oleracea L.) into early medieval Europe caused a shift from these various greens towards the one new plant. A medical use of Garden Orach is documented in the Greek and Roman classical period to promote digestion, regulate metabolism and ease disorders of the female reproductive system. But these applications are equally valid for a plant of similar name (Atriplex sylvestris, wild Orach) which was recently identified as wild beet (Beta vulgaris var. maritima (L.) Thell.). In both cases, metaphysical and medical aspects are neatly entwined, suggesting important traditions of earlier times (Zwiebel, 2024).

Material and methods

Between 2022 and 2023, four cultivars of Garden Orach (A. hortensis) as well as two other wild, non-halophytic Atriplex species were cultivated in my garden in Upper Lusatia / Germany. The phenological and ecological data investigated were published in a previous work (Zwiebel, 2024). As a result, the two species commonly suggested to be wild ancestors of Garden Orach, Atriplex sagittata Borkh. and Atriplex aucheri Moq. were questioned in this role. They were shown to be feral forms of the domesticate, differing mainly in invasiveness.

The A. hortensis cultivars investigated represent different geographic regions. A fully red, yet common European cultivar and golden-red form were taken from the same garden, where they have been grown for more than 20 years.

The repeated sensation of the leaves' saltiness inspired the experimental setup. A purple-greenish form was obtained from a gardener's seed collection in Southern Georgia / Caucasus, and a light green form from an Albanian gardener's collection South of Tirana (See Figures 2, 3)1. Additionally, an assemblage of twelve non-Atriplex species of ruderal or horticultural distribution was grown in the garden for comparative reasons. They covered a taxonomical range as wide as nine families. Their seeds were obtained from local stands.

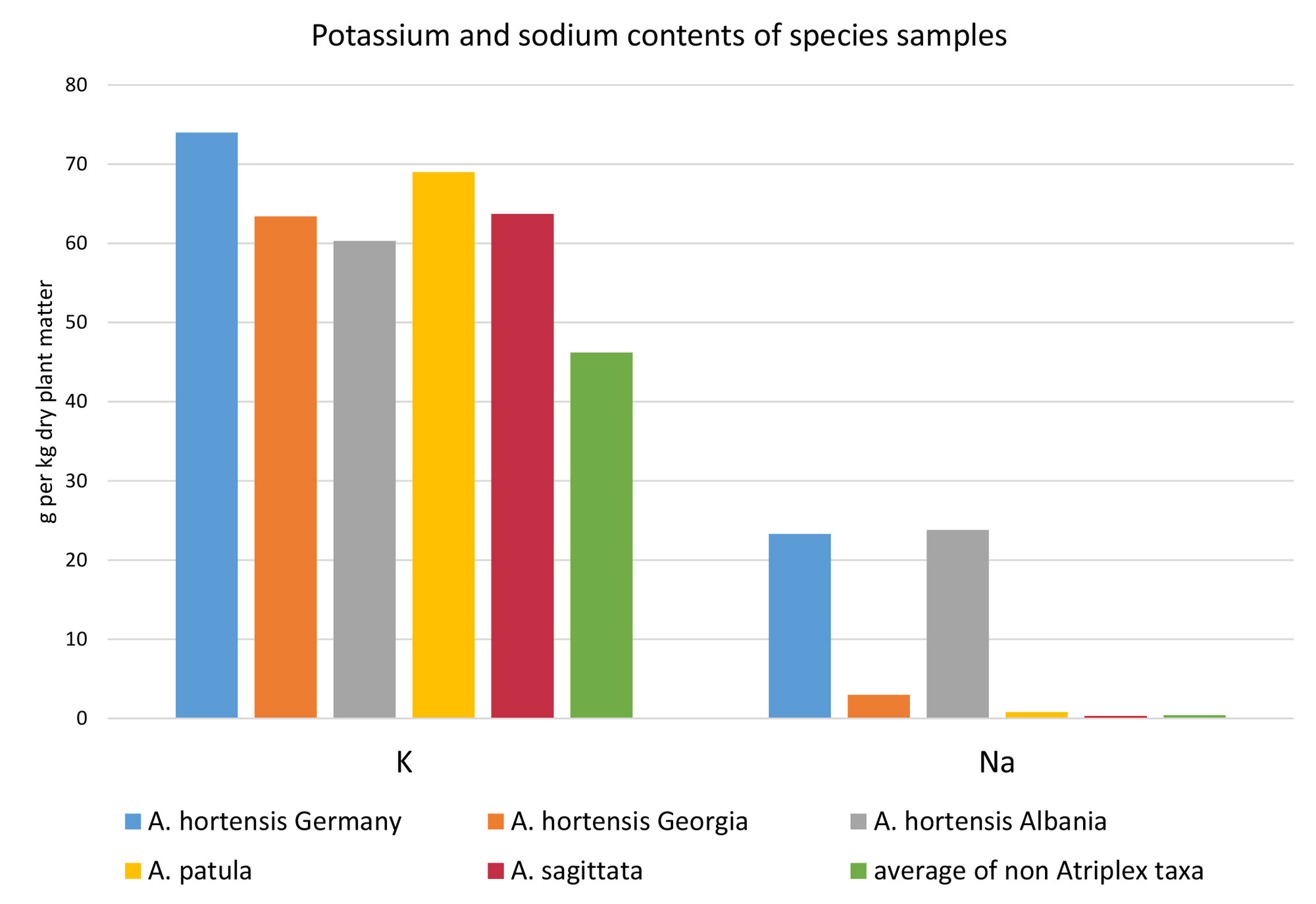

A mixed sample of eight individuals per species at the time of expected maximum growth was prepared for nutrient analytics as shown in Table 1. The concentrations of sodium and potassium in different Atriplex species was compared to data of the non-Atriplex species.

The analytics were carried out by LKS Laboratory using accredited methods.2

In a practical approach, 15 kg of full-grown Atriplex hortensis (green and red form) as well as 5,5 kg of Atriplex patula L., were dried and burnt, saving their ash completely. This was done in a steel pan over an open fire, which is no procedure expected for prehistory. But it provided the possibility to heat the samples till they were thoroughly fired. A small portion of Garden Orach ash was ground and reheated to about 700°C to achieve maximum oxidation.

The sodium and potassium content of Garden Orach´s ashes were analysed by using the standardised methods cited above.

In a first culinary setup, ashes of the two Atriplex species as well as wooden ash of European Spruce (Picea abies (L.) H.Karst.) were separately applied to fresh loaves of goat cheese, each measuring 400g, which was matured at 10 to 14 °C for seven months, not using any conventional salt.

A second way to substitute salt was tested in lactic acid food preserves. Two four-liter glass jars were filled with different fresh foodstuffs, Orach ash, and inoculated with whey. Both jars were covered and fermented at ca. 15 °C for three weeks, afterwards stored at 10 to 12°C over five months. No additives were used. The first jar contained sprouted grain (wheat), red beets, crab apples (Malus sieversii M. Roem.) and chili peppers and was covered with a suspension of water and 60 g of Garden Orach ash. The second jar contained cornel fruits (Cornus mas L.), rowanberries (Sorbus aucuparia L.), and leaves of perennial pepperweed (Lepidium latifolium L.) with a suspension of 200 g Garden Orach ash3. The consistency, smell and taste of the preserves were investigated at the end of storage time.

Additionally, Garden Orach ash was soaked in water and drained followed by evaporating the water from the brine. The resulting salt was analysed, tasted, and used with food.

Results

Rich garden ground and common cultivation methods, which did not involve chemical fertilizers or pesticides, offer optimum growing conditions for all domesticates and weeds investigated. Most species grew taller and more vigorous than documented in literature (powo 2024). The various analysed species naturally offer a wide range of specific nutrient contents (See Table 1).

| Species | K | Ca | P | Na | Mg |

| Atriplex | |||||

| Atriplex hortensis Germany | 74 | 9.2 | 5,9 | 23.3 | 10.1 |

| Atriplex hortensis Germany repeated | 21.9 | ||||

| Atriplex hort. Georgia | 63.4 | 9.2 | 3.1 | 3 | 7.2 |

| Atriplex hort. Albania | 60.3 | 8.4 | 5.5 | 23.8 | 7.3 |

| Atriplex patula | 69 | 16.7 | 5.5 | 0.8 | 7.6 |

| Atriplex sagittata | 63,7 | 8.2 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 6.9 |

| Atriplex hortensis ash (Germ.,Alb.) | 215 | 38.1 | 19.7 | 55.7 | 29.6 |

| non Atriplex taxa | |||||

| average of non Atriplex taxa | 46.2 | 18.5 | 3.9 | 0.42 | 3.8 |

| Allium sativum | 29.6 | 27.7 | 1.6 | 0.18 | 3.7 |

| Tussilago farfara | 46.4 | 32.9 | 2.5 | < 0.2 | 5.8 |

| Petasites albus | 57.4 | 25 | 3.7 | < 0.2 | 4.9 |

| Chenopodium album | 55.1 | 15.4 | 4.6 | 0.08 | 5.3 |

| Echinochloa crus galli | 47.6 | 4.2 | 5.5 | 0.4 | 5 |

| Heracleum sphondylium | 55.4 | 14.2 | 5.2 | 0.18 | 2 |

| Hyoscyamus niger | 43.2 | 10.5 | 3.9 | 0.11 | 5.4 |

| Lepidium latifolium | 29.7 | 17.6 | 3.8 | 0.12 | 3.7 |

| Papaver somniferum | 48.3 | 23.5 | 4.8 | 0.12 | 3 |

| Urtica dioica | 28 | 27.1 | 4.8 | 0.04 | 2.9 |

| Sonchus asper | 54.8 | 11.8 | 3 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| Sonchus oleraceus | 59.7 | 12.2 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| error of measurement % | 7 | 13 | 7.5 | 14 | 9 |

Table 1. Nutrient concentration g/kg dry plant matter of species in horticultural comparison.

The dominant cation found in all species was potassium. Its values in all Atriplex taxa ranged significantly above the average value of the twelve non-Atriplex taxa and still slightly above the maximum value out of these taxa, given by milk thistle (Sonchus oleraceus L.). This was not surprising, as several Atriplex species are known as halophytes and their ash, which is rich in potassium, was sometimes used as washing or baking powder (Atriplex halimus L., North Africa, Atriplex canescens (Pursh) Nutt., South West of US). It is interesting to note that Atriplex hortensis of this investigation is neither considered specialised nor halophytic. This indicates a specific potassium metabolism in Atriplex. The magnesia and calcium contents for all Atriplex taxa were close to the average value of the twelve non-Atriplex taxa. Sodium concentrations were by far the most variable of all measured nutrients, ranging from 0,04 g/kg dry plant matter in stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.) to 23,8 g/kg dry matter in Garden Orach from Albania. There was a distinct gap between the Garden Orach cultivars and all other samples (See Graph 1).

Graph 1. Potassium and sodium contents of species samples.

Non domesticated Atriplex sagittata Borkh. and Atriplex patula L. showed sodium concentrations close to the twelve non-Atriplex taxa.

The outstanding sodium content for Garden Orach from Germany and Albania was ten to forty times higher than in all other investigated taxa. The first test of red Artiplex hortensis was repeated due to its high sodium content, which was first believed to be an error in analytics. Later the Albanian Atriplex hortensis cultivar supported the unexpected results. Garden Orach from Caucasus was found slightly above the milk thistles value (Sonchus asper (L.) Hill) but still far below European Garden Orachs.

Ethnologically documented PAS use starts with the combustion of plant material. So did my experiments. The weight of 15 kg Garden Orach fresh plant matter yielded 0.58 kg ash. It was very unexpected to find the ash totally black, coarse and dense, other than the light gray ash of Atriplex patula or wood. A smaller portion of Garden Orach ash was ground and reheated in a steel pan to red glow (ca. 700°C). But even this procedure did not burn the carbon fully and left a melted clump of black colour (See Figure 4). The taste of garden Orach ash was remarkably salty, as indicated by the analytics. The K/ Na ratio in ash was widened in comparison with plant dry matter. On the other side, the K/ Ca and K/ Mg ratios were narrowed in the same samples. This might indicate a minor volatilisation of sodium in the heating process even though the maximum measurement uncertainty allows alternative interpretation.

The next step involved fresh goat cheese (each 400g), manufactured without any salt, of which one was placed in 150g Garden Orach, black ash; a second one in 180 g Atriplex patula ash; and a third one in 180g wooden ash. They were matured over seven months in separate jars. The samples were not touched throughout the time of storage (See Figures 5, 6). In cutting the cheese they showed colours of different shades of amber. There was no sign of rot or fungi found on any of the cheeses, either on the surface nor in the interior. The wooden ash sample was soft as Camembert and showed few holes. The Atriplex patula cheese resembled the consistency of young hard cheese but showed major holes. The Atriplex hortensis cheese was hard as matured hard cheese and showed little holes in the central part of medium colour. The outer part of beige colour had a distinctive dark horizon defining the central part. Twelve people aged between 25 -72 tasted the cheese samples4. The vast majority favored the garden Orach ash loaf, describing it as being mild and typical savory with a slight bitterness. Especially the people with a passion for matured hard cheese gave good notes for smell and taste.

The Atriplex patula cheese caused the sensation of increased tingling bitterness on the tongue but still was classified as edible by four people, especially when eaten in small amounts on bread. One person described the taste as over-salted without bitter side effects.

The bitterness of wooden ash cheese was still increased, which made the final product not palatable to the test persons.

Fermentation bubbles within the cheese were present to different extents. It was similar for wooden ash and Atriplex hortensis cheese and obviously increased in Atriplex patula cheese. The reason for this remains unclear because all three cheeses were manufactured from one cheese curd shared the same resting time.

The excellent conservation and maturing of all cheeses are believed to be the result of combined alkaline concentration and antimicrobial carbon-rich compounds in the ash. Thus, several plant ashes may substitute common salt in cheese with only the exception of taste.

The final control of fermented food from the jar containing wheat, crab apples, red beets, and chili peppers revealed a preserve of rather unpleasant smell, indicating other microbes besides the lactic acid bacteria. Insoluble black compounds floated on top and separated the surface mould well from the preserve. The ingredients were of proper consistency, only some red beets grew feeble and soft. The liquid was tinted dark red by betanins, whereas the black ash did not affect colour. Wheat, chili peppers, and crab apples were preserved in consistency, form and colour. Three people, including myself, tried a few crab apples, wheat, and beet slices without negative effects. The crab apples were highly astringent and bitter as raw fruit, but the specific malo-lactic fermentation lowers the tannin and malic acid content in the process to a palatable degree. Because of the smell, the test must be considered as partially failed.

The jar with cornel and rowanberry showed many similarities to the first one. The insoluble black compounds floated on top and inhibited surface mould, nevertheless the black colour did not affect the foodstuffs. Consistency and colour were found close to the fresh plant parts with some bleaching. Smell and taste were described as typical for fermented vegetables without negative sensations. The bitter and malic acid taste in fresh cornel and rowanberry again was lowered to a palatable degree in fermentation. The good result of the second test was primarily ascribed to the increased amount of Garden Orach black ash. The concentration of both alkali (sodium and potassium) in this four-liter setup was estimated as being within the recommended concentration in conventional salt fermentation (one to five percent).

Rinsing black ash with little water, draining off the brine and evaporating the water left a crystalline, nearly white and transparent salt, which was used in cooking, on hard-boiled eggs and tomatoes with little difference to pure NaCl (See Figure 7).

Discussion

High alkaline concentrations in Atriplex are commonly interpreted as a storing mechanism of surplus K or Na from saline ground in special tissues to avoid salt stress in other parts of the plant (Calone et al., 2021). Contrarily, the garden experiments indicate a high metabolic extra effort to absorb these alkaline amounts in a non-saline environment. Therefore, the increased sodium and potassium concentrations in Garden Orach from Europe are likely to be genetically fixed. If so, it has to be considered a domestication trait even though the related exploitation is absent from current Old World practice. Whether the lower sodium concentrations in the cultivar from Southern Georgia represent a distinct difference between European and Asian cultivars cannot be judged by a single domestic descent. Nevertheless, the recent identification of A. sagittata as a feral form of A. hortensis caused by the selection of green cultivars in Europe of the historical time argues for the loss of this trait in a process of feralisation (Zwiebel 2024). If more Asian autochthonous Garden Orach cultivars can be detected showing reduced sodium concentrations, the hypothesis of several independent domestications in Eurasia may be suggested as well as repeated feralisation- domestication processes.

Analytical data on nutrients of major crops worldwide are abundantly available in agricultural research papers. I was not able to find any sodium concentration as high as in European Garden Orach (See Table 1).

The most striking result of the cheese experiments lies in the simplicity of the maturing process. Manufacturing hard cheese normally demands precise daily maintenance. The curd has to be turned and swept with salty water allowing the intervals to widen slowly. The Atriplex hortensis cheese displays a tasty product like modern hard cheese, but of remarkably reduced effort and maintenance. This method has not been recorded before but once accepted it might indicate the early origin of French Morbier cheese, which is interlaved with ash until present day. It also offers an easy way to transfer even small amounts of milk into storable cheese.

Saltiness of black ash from Garden Orach corresponds to ethnobotanical data from Papua New Guinea where ashes of black colour were readily consumed as a salt substitute (see background). A similar distinction was made by Aristoteles (ca. 300 BP) and Pliny (ca. 50 BP) (Hehn, 1919, p. 18). Both authors described a 'barbarian' technology of combusting brine-soaked plant material and using the coal-like black residue instead of salt.

The concentration of 5,7 % sodium in Garden Orach ash surpasses most documented PAS species. Ash of Maytenus vitis-idaea Griseb., an important PAS shrub from South America contains 2.27% sodium, whereas ashes of African indigenous PAS species are found even below 2% sodium (Schmeda Hirschman, 1994; Phanice, 2016). Only Melaleuca spec. and Acacia mangium wild trees in the PAS tradition of Papua New Guinea were documented containing more than 10% sodium (Ryutaro et al., 1987).

But many of such sodium rich PAS plants show decreased potassium values. In Garden Orach both alkalines are prominently concentrated. Potassium substitutes sodium to some extent in taste and food preservation (see background), especially in the context of lactic acid fermentation. This makes the ash even more valuable as salt substitute.

The technique of lactic acid fermentation is considered an ancient tradition of great importance and wide distribution (Montet et al. 2014) . Furthermore fermentation, similar to salt itself, improves preservation, digestibility, and taste of many vegetal foodstuffs. But lactic acid fermentation produces storable food only with considerable amounts of salt added, which also helps to prevent other microbial invasion. The presence of abundant plant food as well as some sort of salt are crucial factors in food preservation for many indigenous communities (Sibbesson, 2019). If the salt comes from a PAS source such as garden Orach, it is dominantly present as carbonate and converted into sodium and potassium lactate during the fermentation process. These lactates have proven to be antimicrobial5. Interestingly, the taste of potassium lactate is described being mild and neutral, whereas its carbonate has a bitter taste (Hoffmann, 2024). That means lactic acid fermentation improves not only the foodstuffs taste, but also the taste of PAS itself.

Unfortunately, the PAS tradition of Papua New Guinea is not linked to this region's important tradition of earth pit fermentation of taro, sago, and others (Greenhill et al., 2009; Gubag et al., 1996).

Prehistoric archaeology has documented numerous earth pits filled with dark humous material layered with various seeds and foodstuffs all through Europe. These pits, which are dominantly interpreted as waste disposals, were suggested as fermentation pits by Hahn (1935) and Zwiebel (2022). Besides humification it might have been black PAS, that contributed to the dark colour of the pitfill. Whether only Atriplex hortensis might serve for this purpose is left to future research.

The dark colour gives an exciting opportunity to interpret a yet mysterious Greek plant name: Theophrastos (1916, p. 97) mentioned Garden Orach several times in his "Inquiry on plants" ca. 300 BC. According to Renaissance and modern scholars the identification of this plant bears no doubt. The premium name given by Theophrastos is Atraphaxys (ἀτράφαξυ). Among later Greek and Roman writers this name was transferred to Andraphaxos and similar lemmata of unclear etymology. In search for a meaning, I encountered the term Teutlophaxys (τευτλοφαχη), a word of related structure from the Materia Medica (Dioscorides, 2000, p. 267) which was interpreted by Löw (1926, p. 349ff.) as a mixed dish of teutlon (red chard) and phakos (lentil). But Dawkins (1936) stated, that the old Greek meaning of phakos was simply a collective term for plants used by humans, similar to -worth, as in Wormworth (Artemisia vulgaris L.) and others. This linguistic background allows an interpretation of Andraphaxos as a compositum of antrax (coal) and phakos (plant). This would relate to the coal black ash of Garden Orach sufficiently. Whether this use of the plant in 300 BC was still practiced or only remained in a name without meaning cannot be currently clarified. There is good evidence, that Garden Orach had great importance in ancient ritual, religion and medicine, before it was disregarded in Greek and Roman times and eventually forgotten (Zwiebel, 2024).

Coltsfoot

The only plant from temperate regions, related to PAS use is poorly documented. Coltsfoot leaves are repeatedly mentioned as a salt substitute used by Native North American communities. Coltsfoot is the common name for several plants of which introduced and invasive European Tussilago farfara (L.) and indigenous Petasites frigidus (L.) Fr. are the most common ones. Both species are closely related within the Asteraceae family and share morphological similarities, such as flowers appearing separately weeks before the leaves.

The first mention as a Native American PAS is Hall (1976). Since then, it is often copied and newly stated in outdoor manuals, nature guides, cookbooks, and papers on indigenous culture (Adamant, 2018; Coffey, 1993; Fertig, 2024, Strauch, 2024; AISD 2024). In literature positive sensual tests for one or both plants, often insufficiently separated, are reported side by side with inconclusive descriptions6 (Hall, 1976; Coffey, 1993; Fertig, 2024; Wikihowto, 2024). A more sceptical group, including myself, links the taste to wooden ash, salty but dominated by a bitter note (Adamant, 2018; Strauch, 2024). This and the absence of alkaline analytics in the literature available made me include Coltsfoots in the Garden Orach investigations.

Petasites frigidus is not present in Europe so instead I analysed leaves of its close relative Petasites albus (L.) Gaertn.

Plants of Tussilago farfara and Petasites albus were sampled from wild stands close to my garden. The sodium values in the leaves of both plants were found below 0,2 g/kg dry matter, which is far below the average value of all non-Atriplex plants (See Table 1). Tussilago farfara flowers, appearing separately early in spring, yielded sodium concentrations similar to the leaves. These analytic results of the European samples given do not support a special qualification of either plant for PAS use.

The most frequently mentioned method for Coltsfoot salt preparation starts with picking the leaves. In a semi-dry state they are rolled and fixed until fully dry. Then they are lit and burnt slowly between fingers or in a shallow bowl. Foliage of both Coltsfoots are not easy to dry due to the white coating underneath. The single-leaf technology accompanied by a slow drying process leads to an immense effort for seasoning. This method is not appropriate in daily use, but it points to the origin of a possible misinterpretation. European Coltsfoot is known for curing asthma and severe cough, as well as toothache by its smoke. This was common in Roman times (Plinius, 1906) and still in 19th and 20th century herbals, when cigars of Tussilago farfara were commonly provided by drugstores (Osiander, 1817; Künzle, 1945). Similar properties and applications were attested to leaves of Datura stramonium L. and European Petasites hybridus (L.) G.Gaert., Mey & Scherb. Due to their antispasmodic and narcotic virtue, they were not only consumed as medicine but whenever tobacco was not available. Therefore the method reported for Native American Coltsfoot salt imitates the use of Tussilago farfara in European herbal medicine, a tradition currently lost.

Therefore Coltsfoot should not easily be considered a PAS but likely got there due to the outlined medicinal confusion. A reevaluation of historical data, oral tradition and analytics is left to further investigations.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank R. Bussmann (Ilia State University, Tbilisi), J. Büchner (Senckenberg Museum für Naturkunde, Görlitz) and Neil Peterson (Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada) for contributing to this paper’s structure and details, as well as all friends and family members involved with testing leaves, ash, fermented food, and cheese, and the seedbank of IPK Gatersleben/Germany for providing cultivar seeds and LKS laboratories Lichtenwalde/Germany for analytics.

Abbreviation

PAS = salt in and from plant ash

- 1

Both women donated the seeds to the seedbank of Leibniz-Institut für Pflanzengenetik und Kulturpflanzenforschung (IPK) OT Gatersleben Corrensstraße 3 06466 Seeland / Germany, where I purchased them in 2022. More detailed information on seed sampling is available using the identification numbers (Southern Georgia: 10.25642/IPK/GBIS/84691, Atri 21 , Albania 10.25642/IPK/GBIS/59539

- 2

LKS Futtermittellabor, August-Bebel-Str. 6, 09577 Niederwiesa OT Lichtenwalde/ Germany using the standardized method VDLUFA III, 3.1, 1976 for dry matter content and DIN EN ISO 11885:2009-09 an inductively coupled plasma optical atomic emission spectrometry for Ca, K, Mg, Na concentrations. The measurement uncertainty was calculated between 7% (potassium) and 14 % (sodium). This did not affect the interpretability of results.

- 3

A savory fermented dish of cornel fruits is known as Polish olives or Balcan olives.

- 4

The sample set comprised six female and six male participants.

- 5

They are legal food additives without maximum limitation, sodium lactate being E325, potassium lactate E326.

- 6

Seasoning without being salty or ash only to be added in minor amounts.

Bibliography

Adamant, A., 2018. Extracting Salt From Plants for Survival Available at < https://practicalselfreliance.com/coltsfoot-salt/ > [Accessed 02 March 2024].

AISD (American Indian Society of Delaware), 2024. Culinary ashes. Available at< https://udaisd.proboards.com/thread/620/culinary-ashes > [Accessed 11 March 2024].

Bogaard, A., 2004. Neolithic Farming in Central Europe: An archaeological study of crop husbandry practices. London: Routledge.

Breslin P. A. S. and Beauchamp G. K., 1995. Suppression of bitterness by sodium: Variation among bitter taste stimuli, Chemical Senses 20(6), pp. 609-623.

Calone R., Cellini A., Manfrini L., Lambertini C., Gioacchini, P., Simoni A. and Barbanti L., 2021. The C4 Atriplex halimus vs. the C3 Atriplex hortensis: Similarities and Differences in the Salinity Stress Response, Agronomy 11(10), p. 1967. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11101967.

Coffey, T., 1993. The History and Folklore of North American Wild Flowers. New York: Facts on File.

Cozzo, G., 2024. Seasoning and the Sacred: Historical Use of Salt and Ashes among the Cherokee. Society of Ethnobiology. Available at: < https://ethnobiology.org/seasoning-and-sacred... > [Accessed at 12 February 2024].

Dawkins, R. M., 1936. The Semantics of Greek Names for Plants. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 56/1, pp.1-11.

Dioscorides, 2000. De Materia Medica - Being an Herbal with many other medicinal materials. Edited by T.A. Osbaldeston and R.P.A, Wood. Johannesburg : IBIDIS.

Echeverri, J. A. and Enokakuiodo, R. J., 2013. Ash salts and bodily affects: Witoto environmental knowledge as sexual education, Environmental Research Letters 8(1): p.13. Available at: < https://www.researchgate.net/publication/.../a> > [Accessed 21 March 2025]

Fertig, W., 2024. Plant of the Week: Petasites frigidus /var. . US Forest Service Available at < https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/... > [Accessed 02 March 2024].

Gopalakrishnan, J., 2015. Physico-chemical analysis of traditional vegetal salts obtained from provinces of Papua New Guinea, Journal of Coastal Life Medicine 3(6): pp. 476-485. DOI:10.12980/JCLM.3.2015JCLM-2014-0120.

Greenhill, A. R., Shipton, W. A., Blaney, B. J., Brock, I. J., Kunz, A. and Warner, J.M., 2009. Spontaneous fermentation of traditional sago starch in Papua New Guinea, International Journal of Food Microbiology 26(2), pp. 136 - 141. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.10.004.

Gubag, R., Omoloso, D.A. and Owens, J.D., 1996. Sapal: a traditional fermented taro [Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott] corm and coconut cream mixture from Papua New Guinea, International Journal of Food Microbiology 28(3), pp. 361-367.

Haberlandt, M., 1913.Die Kochkunst der Primitivvölker. Jahresschrift des Vereins zur Verbreitung naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse. Wien: Verlag der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Österreich.

Hahn, E., 1919. Von der Hacke zum Pflug (2.ed.). Leipzig: Quelle und Meyer.

Hahn, I., 1935. Die Auswahl der zur Dauernahrung genutzten Pflanzen. Sitzungsberichte d. Gesellschaft d. Naturforschenden Freunde zu Berlin 1934(1935), pp. 258 - 281.

Hall, A., 1976. The Wild Food Trailguide - New And Expanded Edition. New York: Holt Rinehart Winston.

Hall - Wattens Tourismus, 2024. Die Entdeckung des Salzberges im Halltal bei Absam. Hall Wattens Austria. Der Salzbergbau. Available at: < https://www.hall-wattens.at/de/salzbergbau-zu-hall.html > [Accessed 22 January 2024].

Hehn, V., 1919. Das Salz - eine kulturhistorische Studie. Leipzig: Insel Verlag.

Henney, J. E., Taylor, C. L. and Boon, C. S., 2010. Taste and Flavor Roles of Sodium in Foods: A Unique Challenge to Reducing Sodium Intake. In: J.E. Henney, C.L. Taylor and C.S. Boon, eds. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press, pp. 67-90.

Hoffmann, L., ed., 2024. Kaliumlaktat, Natriumlaktat, ETC GmbH - Chemikalienhandel weltweit. Available at: < https://www.etc-nem.de/Chemikalien-1/... > [Accessed 06 June 2024].

Kronzucker, H. J., Coskun, D., Schulze, L. M., Wong, J. R. and Britto, D. T., 2013. Sodium as nutrient and toxicant, Plant Soil 369, pp.1-23. Available at < https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/... >. [Accessed 21 March 2025]

Künzle, J., 1945. Das grosse Kräuterheilbuch. Freiburg im Breisgau: Otto Walter Verlag.

Löw, I., 1926. Die Flora der Juden. Vol.1,5. A. Kohut Foundation. Wien: Löwitt.

Lueger, O., 1904. Lexikon der gesamten Technik und ihrer Hilfswissenschaften, Bd. 1 Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-anstalt.

McCaughey, S. A. and Scott, T. R., 1998. The Taste of Sodium, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 22(5), pp. 663-676. Available at: < https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-04688-006 >

Montet, D., Ray, R. and Zakhia-Rozis, N., 2014. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Vegetables and Fruits. doi 10.13140/2.1.2374.1127.

Okoli, I.C., 2023. Traditional vegetal salts as substitutes for common salt. Tropical research reference platform. Available at < https://researchtropica.com/traditional-vegetal.../ > [Accessed 02 March 2024].

Opio, C. and Bergeso, T. L., 2016. Elemental composition and potential health impacts of Phaseolus vulgaris L. ash and its filtrate used for cooking in Northern Uganda, African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 16(4), pp. 11351-11365. DOI:10.18697/ajfand.76.16170.

Ortuño, J. A., Verde, A., Fajardo, J., Rivera, D., Obón, C. and Alcaraz, F., 2021. Halophytes in Arts and Crafts: Ethnobotany of Glassmaking. In: M.N. Grigore, ed. Handbook of Halophytes. Springer, Cham, pp. 1-10 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57635-6_106.

Osiander, J. F., 1817. Nachrichten von Wien über Gegenstände der Medicin, Chirurgie und Geburtshilfe. Tübingen: Bey Christian Friedrich Osiander.

Phanice, W. T., 2016. Analysis of micronutrients and heavy metals of indigenous reedsalts and soils from selected areas in Western Kenya. PhD thesis. Egerton University Kenya. Available at: < http://ir-library.egerton.ac.ke/... > [Accessed 20 May 2024].

Plinius, 1906. Naturalis Historia, vol. 2. Edited by K.F.T. Mayhoff. Leipzig: Teubner.

Powo, 2024. Atriplex hortensis. Available at: < https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/... > [Accessed 21 March 2025]

Ryutaro, O., Suzuki, T. and Morita, M., 1987. Sodium-Rich Tree Ash as a Native Salt Source in Lowland Papua, Economic Botany, 41( 1), pp. 55-59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02859348.

Saile, T., 2012. Salt in the Neolithic of Central Europe: production and distribution. In V. Nikolov and K. Bacvarov, eds. Salz und Gold: die Rolle des Salzes im prähistorischen Europa / Salt and Gold: The Role of Salt in Prehistoric Europe. Provadia & Veliko Tarnovo, pp. 225-238.

Schmeda-Hirschmann, G., 1994. Tree Ash as an Ayoreo Salt Source in the Paraguayan Chaco, Economic Botany, 48(2), pp. 159-162. Available at < https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02908207 >

Shurpin, Y., 2024. Why the Bread & Egg in Ash Before 9 Av?. Chabad library article. Available at < https://www.chabad.org/library/... > [Accessed 12 March 2024].

Sibbesson, E., 2019. Reclaiming the Rotten: Understanding Food Fermentation in the Neolithic and Beyond, Environmental Archaeology, Journal of Human Palaeoecology 27, pp. 111-122. DOI: 10.1080/14614103.2018.1563374.

Stöllner, T., 2007. Siedlungsdynamik und Salzgewinnung im östlichen Oberbayern und in Westösterreich während der Eisenzeit. In: J. Prammer, R. Sandner and C. Tappert, eds. Siedlungsdynamik und Gesellschaft. Beiträge des internationalen Kolloquiums Straubing 2006. Jahrbuch des Historischen Verein Straubing. Sonderband 3. Straubing, pp. 313-362.

Strauch, B., 2024. Herbs to know: Coltsfoot, Motherearthliving. Available at: < https://www.motherearthliving.com/gardening/... > [Accessed 22 February 2024].

Syndicat Interprofessionel Morbier, 2025. The history of Morbier cheese. Available at: < https://www.fromage-morbier.com/... > [Accessed 25 February 2025].

Theophrastos, 1916. Inquiry into Plants and minor works on odours and weather signs, vol. 2. Edited by A. Hort. London: W. Heinemann.

Venable, E. M., Machanda, Z., Hagberg, L., Lucore, J., Otali, E., Rothman, J. M., Uwimbabazi, M. and Wrangham, R., 2020. Wood and meat as complementary sources of sodium for Kanyawara chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), American Journal of Physiological Anthropology. 172(1). doi: 10.1002/ajpa.24029.

wikihow.com, 2024. Extract salt from plants. Available at: < https://www.wikihow.com/Extract-Salt-from-Plants > [Accessed 02 March 2024].

Zwiebel, L., 2022. Pit preserve from Ida- On the problem of charred seeds from prehistoric pits, EXARC journal 2022/3. https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10651.

Zwiebel, L., 2024. Die geringgeschätzte Gartenmelde (Atriplex hortensis L.) - Geschichte, Farben, Bedeutung, Mitteilungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft der Oberlausitz 32, pp. 101-128.