The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Reviewed Article:

An Experimental Reconstruction of Hair Colours from the Jin and Tang Dynasties (265-907 AD) in China

Hair colours, as a daily cosmetic used in ancient Chinese life, often appear in ancient Chinese medical books, according to types, and can be classified into herbal hair colours and mineral hair colours. Experimental reconstruction of herbal hair colours and mineral hair colours was carried out to explore the influence of factors such as the type and material of hair colours on the colouring effect. Meanwhile, the experiments were recorded and analysed using a stereo microscope. The experimental results show that the ancient hair colours are authentic and it is feasible that mineral hair colours and herbal hair colours are capable of colouring hair. Mineral hair colours have better colour fastness and colouring effects than herbal hair colours.

Introduction

In China, ancient hair colours can be categorised into herbal and mineral hair colours. Since the Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD), the recipes for herbal and mineral hair colours have been clearly documented in ancient books, such as Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang (The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies), compiled in the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420 AD), who recorded ‘ran faxu, bailingheifang’ [a prescription for colouring white hair and beards black] (Ge, p.146), a hair colour using vinegar and beans as raw materials to colour grey hair to turn it black. During the Tang Dynasty, some of the medical recipes from the Jin Dynasty were continued; for example, Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang (Arcane medical essentials from the Imperial Library; See glossary of Chinese terms) contained a large number of Chinese medical recipes from the Tang Dynasty and before. It also goes into more detail about the specifics of the dosage and administration of the recipes, the methods of operation, and other details.

Regarding archaeological discoveries in China, relatively few coloured hair samples and actual hair colours have been found, and proving the exact recipe and production process of hair colours remains challenging. The use of experimental archaeology has the possibility to link historical sources with findings made during archaeological excavations, providing one of the most effective complementary methods to check the accuracy and usefulness of historical sources (Ferrari, et al., 2021), and to understand better the phenomenon of colouring that occurs in the process of description versus the actual effects. In addition, experimental archaeology can fill in the gaps in the descriptions of historical sources and better appreciate the objective feelings of the actual hair colouring process from the perspective of ancient ancestors, as a bridge between the ancient and modern worlds, which can help to discover relics of phenomena that may have been overlooked during the archaeological excavations (Tang, 2023, pp.42-43).

Through the experimental reconstruction of herbal hair colours and mineral hair colours from the Jin and Tang Dynasties based on historical sources, the preparation and use of hair colours are explored in depth, and the composition of the recipes, methods of preparation, and effects of actual use of hair colours are analysed. These provide practical insights into the study of ancient Chinese medical sources and ancient cosmetic products, helping to discover the phenomenon of hair colouring and the cultural relics related to hair colouring that may have neglected in the process of archaeological excavations.

The colouring hair traditions of ancient traditional Chinese medical cosmetology

Ancient Chinese ancestors had the aesthetic concepts of ‘dense hair symbolises health’, ‘black hair symbolises beauty’, ‘long hair symbolises affluence’, and the traditional hairdressing of hair shampoo, hair growth, black hair, moisturising, and colouring (Kong and Zhang, 2017, pp.178-181). Hair colouring, as an important part of the process, was often used by ancient peoples to turn grey hair caused by age and hereditary factors into black in order to express the aesthetic concept of ‘black hair symbolises beauty’.

From the Warring States period (475-221 BC) to the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD), Chinese people of the past had already been concerned about the problem of grey hair, and treated it through internal treatment with traditional Chinese medicine. Huang Di Nei Jing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon, (See glossary of Chinese terms)) written during this period, for the first time elucidated the pathogenesis of grey hair from multiple perspectives, arguing that hair growth related to essence, qi, blood, and emotional factors, and also illuminated the relationship between the internal organs and hair (Wu, et al., 2022, p.109). A number of lacquer lians [a utensil used in daily life in ancient China for a variety of purposes, such as a dressing utensil] have been unearthed from the Mawangdui No. 3 Han Tomb (See Figure 1), one of which is a small round lian, that contains a black sauce-like substance, which is the Han Dynasty head oil langao [the oil made from Lycopi herba in ancient China, used to light lamps and as a moisturising oil for hair], which has the function of caring for the hair and is used in conjunction with the fu [a kind of straight brush in ancient China] (See glossary of Chinese terms and Figure 2), unearthed in the same tomb, which makes the hair smooth and manageable (Hunan Provincial Museum and Hunan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, 2004, p.148; Wang, 2015, pp.23-24). In addition, excavation of the Mawangdui Han Tombs has also unearthed a large number of medical silk manuscripts (See Figure 3), in which the Yangshengfang (Prescription of Health Maintenance; See glossary of Chinese terms) recorded a special prescription for ‘heifa’: “heifayiqi, qu ... xing, fucheng, yi yi fuxing ... shi, huo mu jue, sa ... zhi, yi ... guo, ... bayue weiyao” (more intermittent missing text, the specific meaning of the text is unknown) (Wei and Hu, 1992, p.45; Qiu, 2014, p.117), although the medical silk manuscript is affected by the environmental factors of the burial, some of the text and the title of the prescription in the medical silk manuscript has been lost (unrecognisable), but still can be in accordance with the existing text, it can be presumed that in the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC-8 AD) there was a the use of Chinese herbal remedies to achieve the effect of ‘heifa’. Hanshu records “Mang wenzhi yukong. Yu waishi zian, nai ran qi xufa, jin suozheng tianxia shunv duling shishinv wei huanghou, pin huangjin sanwanjin, chema, nubi, zabo, zhenbao yi jubaiji” [Wang Mang was even more terrified when he heard the news. Wanting to show to the outside world that he was in a stable mood, he coloured his hair and beard black, summoned in the beautiful women of the whole country whom he had recruited, and made the daughter of the Shi Family of Duling County his empress, sending a bride price of 30,000 catties of gold, and hundreds of millions of valuables such as carriages, horses, slaves, all kinds of silks and precious jewels] (Ban, 1962, p.4180). Even though the book does not point out the specific materials and steps used for the colouring of the hair, it can still be assumed that this is the first time that Wang Mang had coloured the hair in his family. Although the book does not indicate the specific materials and procedures for colouring hair, it can still be assumed that hair colours already existed in this period for colouring hair and beards.

During the Six Dynasties period (220-589 AD), as traditional Chinese medicine continued to improve and develop, it also enriched the content of Chinese medical cosmetology, with medical practitioners critically inheriting the experience of cosmetic prescriptions from before the Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD). At the same time innovations were made in line with the needs of the people and began to combine treatment with cosmetic health care (Wu, et al., 2022, p.110). As mentioned above, Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang recorded ‘ran faxu, bailingheifang’, which indicated that the recipes required for hair colours include vinegar and black beans, and that hair colours are prepared by decocting the two recipes. It also says that hair colours are characteristically black lacquer in colour, and the effect of the use of hair colours is to produce black lacquer colours, which is a type of herbal hair colour.

Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang, compiled by Wang Tao in the Tang Dynasty, contained medical prescriptions and techniques, medical matters, and medical books of more than seventy medical practitioners from the Qin, Han, and Sui and Tang Dynasties, and is a collection of various prescriptions and medicines before the middle Tang Era (Fang and Zhang, 2004; Hao and Liu, 1998). In particular, Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang included ‘bixiao ran baifa fang’, which recored “jian xili wudou sisheng, shangyiwei, yi cujiangshui sidou zhu, qu que dou, yi hao huizhi jingxi fa, dai gan, yi douzhi retu zhi, yi youbo guo zhi, jing xiu kai zhi, dai gan, ji yi xiongzhi tu kai, huan yi youbo guo, ji hei ru qi, yitu sannian bubian. Miao yan” [choose four litres of fine-grained black beans as medicine, boil them in four dou of vinegar, take four litres of it, strain the black beans, wash the hair with huizhi, wait for the hair to dry, use the prepared hot bean juice to apply to the hair, then wrap it in oil-soaked silk, and then open the oil-soaked silk to let it dry after one night, immediately use xiongzhi to apply it to the hair, and then wrap it in oil-soaked silk again, the colour of the coloured hair is like black lacquer, and it will remain unchanged for three years1 after applying the hair colour. Very effective] (p.888). This recipe supports the use of a vinegar/black bean liquid as a hair dye. The inclusion of the creation and application processes as well as expected results in a book providing the medical cannon of Jin and Tang dynasties implies a continuity of existence across time.

In addition to herbal hair colours, mineral hair colours also appear in medical texts from the Jin and Tang Dynasties (265-907 AD), such as the ranfafang recorded in Fan Dongyang Fang (See glossary of Chinese terms), compiled by Fan Wang in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, “hufen yifen, baihui yifen, yi jizibai he, xianyi ganshuijiang xi ling jing hou, tuzhi, ji jiyi youbo guozhi yixiu, yi zaodou xique. Heiruan Heiruan bujue, shenmiao” [one fen of hufen , one fen of lime, mix it with egg whites, prepare a sample, first wash the hair with rice water, then apply hair colour, then wrap the hair with oil-soaked silk and keep it overnight, then wash it with zaodou again. Hair colouring is very effective as it leaves the hair dark, soft and black] (p.338). Similarly, this formula was also recorded by Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang and summarised in ‘bian baifa ranfafang wushou’, which is the same as that recorded by Fan Dongyang Fang (See glossary of Chinese terms) in ‘ranfawang’, so it is possible to speculate that there was recognition of this hair colouring formula by the ancients during the Jin and Tang Dynasties.

From the historical sources and archaeological discoveries, some inspiration to examine how ancient people coloured their hair and how they did it during the Jin and Tang Dynasties in China may be obtained. From the perspective of experimental archaeology, the feasibility of the process of hair colour preparation and the actual effect of hair colouring will be analysed through the simulation of the preparation and use of herbal and mineral hair colours. The role that it played in ancient traditional Chinese medical cosmetology will be explored, so that possible phenomena of hair colouring in the archaeological discoveries may be further examined.

Experimental materials

The experimental materials are classified into hair colouring object materials, hair colour materials, and other materials required in the hair colouring process. Hair colouring object materials include youth grey hair samples and elderly grey hair samples. All hair samples are natural and collected from consenting humans. Hair colour materials include black beans, vinegar, hufen, lime, and egg whites, which usually appear in daily life or as medicines. Other materials needed in the hair colouring process include products used in the colouring process, like shampoos that need to be prepared in advance, such as huizhi and zaodou (a combination of materials that will be listed later), as well as conditioning products used after the colouring process, such as animal fat paste and oil-soaked silks. In addition, there are beakers used as containers during experiments and the XTL-165-XTWZ2T, a stereo microscope used for microscopic observation.

Experimental methods

The experiment is divided into three parts: experiment preparation, then experiments 1 and 2. Each experiment is not isolated and has a certain degree of progressivity and relevance. The core of experimental preparation is to prepare for the various materials required in the traditional Chinese medicine hair colours required for Experiment 1 and Experiment 2. This including includes the preparation of grey hair samples, some Chinese medicinal materials, and other materials required for the preparation of the hair colouring process, such as shampoo.

Experiment 1 is based on the bixiao ran baifa fang included in Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang of the Tang Dynasty. The materials include black beans, vinegar, water, and huizhi. It primarily reconstructs an herbal hair colour and the flow of recipe selection, hair colour preparation, hair colour use, and observation of the colouring effect. These serve as a reference value for the study of the ancient natural herbal hair colour preparation and application.

Experiment 2 is the reconstruction of mineral hair colour based on the hair colour included in Fang Dong Yang Fang and Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang, which consists of hufen, lime, egg white, ganshuijiang, zaodou. The reconstruction process is the same as that of herbal hair colours, which provides a reference value for studying the preparation and application of ancient mineral hair colours.

In the experimental process, observation of hair before colouring, shampoo-soaked hair, and hair 30 minutes, one hour, three hours, and 18 hours after colouring was carried out at 21x magnification using a stereo microscope XTL-165-XTWZ2T to record the colour changes and the colour fastness in the process from pre-colouring to post-colouring.

In addition, due to the conversion of ancient Chinese dosage unit and modern dosage unit of the hair colours used in the experiment, one sheng was converted to 200 ml, one liang (See glossary of Chinese terms) to 13.8 g, one dou to 2,000 ml, and one fen (See glossary of Chinese terms) to 3.45 g (Qiu and Yang, 2001; Yang, Fu and Zhang, 2012).

Preparation of experiment

Due to the presence of huizhi, a material that was used as a shampoo in the process of the hair colour for the function of cleaning the hair before colouring in Experiment 1, it needs to be prepared in advance in the preparation of the experiment. Firstly, the plants were burnt and left to cool and stand. The burnt plants were placed in a mortar and ground using the pestle to obtain a black coloured plant ash powder form (see Figure 4) Subsequently, 10 ml of the plant ash was taken and mixed with 80 ml of water to form a light brown coloured liquid (See Figure 5).

Similarly, zaodou was required for the hair colours in Experiment 2, as a shampoo to be used in the hair colouring process. The recipe for zaodou is referenced in the Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang recorded ‘beiji bidou xiang zaodou fang’ and consists of 100 ml of beans (See Figure 6), 27.6 g of Typhonii Rhizoma (See Figure 7), 27.6 g of Chuanxiong Rhizoma (See Figure 8), 27.6 g Radix Paeonlae Alba (See Figure 9), 27.6 g Rhizoma Atractylodis Macroephalae (See Figure 10), 27.6 g Snakegourd Fruit (See Figure 11), 27.6 g Pokeberry Root (See Figure 12), 27.6 g Peeled Peach Seed (See Figure 13), and 27.6 g Chinese Waxgourd Seed (See Figure 14), were subsequently poured into a beaker and mixed and stirred to form zaodou (See Figure 15).

Experiment 1

We used 40 ml of black beans (See Figure 16) and 400 ml of vinegar with strength of nine percent (See Figure 17) and decocted them in the 10:1 ratio of the original recipe. After 40 minutes of decoction, we strained the black beans and extracted 135 ml of the solution to be used as a hair colour (See Figure 18). Subsequently, the two types of grey hair samples were washed using the prepared huizhi. After the hair dried, the prepared hair colour was applied to the prematurely grey hair samples of a youth and then the grey hair samples of an older person, using the prepared hair colours. Then the youthful grey hair samples and elderly coloured grey hair samples were wrapped separately using the oil-soaked silk (See Figure 19, Figure 20). After 8 hours, the youth grey hair sample and the aged grey hair sample were unwrapped for observation of the colouring, and animal fat paste was applied on to them (See Figure 21). The youth coloured hair sample and the aged coloured hair sample were wrapped again using oil-soaked silk, and the oil-soaked silk was unwrapped after 30 minutes for observation.

In the experimental process, using a stereo microscope at 21x magnification to examine the samples, (i) the youthful grey hair samples (See Figure 22) and elderly grey hair samples (See Figure 23) before hair colouring, and (ii) the youth hair samples (See Figure 24) and elderly hair samples (See Figure 25) after washing with the huizhi, and (iii) the youth samples after hair colouring with herbal hair colour, were examined at 30 minutes (See Figure 26 and Figure 27), one hour (See Figure 28 and Figure 29), three hours (See Figure 30 and Figure 31), and 18 hours (See Figure 32 and Figure 33). The microscopic observations were performed to analyse the colour of the samples from before to after hair colouring to detect any trends in colour change (See Table 1).

| Sample Type | Hair Colours Type | Colour observation of Grey Hair Samples | Observation of Huizhi Soaking | Post-staining Observation | |||

| 30 minutes | One hour | Three hours | 18 houres | ||||

| Youth gery sample | Herbal hair colour | Grey in colour | Light yellow in colour | Light brown in colour | Light brown in colourwith localised brown segments | Brown in colour | Brown in colour with fading, local presence of light brown segments |

| Youth gery sample | Mineral hair colour | Grey in colour | Light yellow in colour | Brown in colour with localised presence of dark brown | Brown in colourwith localised dark brown segments | Dark brown in colour | Dark brown in colour |

| Elderly gery sample | Herbal hair colour | Grey in colour | Light yellow in colour | Light brown in colour | Less overall colour change | Light brown in colour with fading, attached to brown spots | Colour fading obvious, light brown in colour overall |

| Elderly gery sample | Mineral hair colour | Grey in colour | Light yellow in colour | The colour appears to be a mixture of brown and dark brown, with the brown being more predominant. | Brown in colour, local presence of dark brown | Brown in colour | Dark brown in colour, local presence of colour fading |

Table 1. Observation of the colouring process of hair colours with an herbal hair colour and a mineral hair colour using the stereo microscope at 21x magnification.

Experiment 2

First of all, the egg was broken and the egg white separated from the yolk, and used to mix 3.45g of hufen (See Figure 34) and 3.45g of lime (See Figure 35) to form a creamy mineral hair colour (See Figure 36). Both hair samples were soaked and washed using ganshuijiang (See Figure 37) mixed with rice and water. The prepared mineral hair colour was applied to the washed samples until they were completely covered (See Figure 38). The youthful, coloured samples (See Figure 39) and the elderly coloured samples (See Figure 40) were immediately wrapped in oil-soaked silk. After resting for 8 hours, the coloured samples were soaked and washed using the zaodou liquid prepared during the preparation of the experiment (See Figure 41). After which the coloured samples were placed in a shady, light-protected environment to await further observation.

Using a stereo microscope at 21x magnification, microscopic observations were carried out on the grey hair samples before hair colouring (See Figure 22 and Figure 23), both samples after washing with ganshuijiang (See Figure 42 and Figure 43), and both samples after colouring with mineral hair colour for 30 minutes (See Figure 44 and Figure 45), one hour (See Figure 46 and Figure 47), three hours (See Figure 48 and Figure 49), and 18 hours (See Figure 50 and Figure 51). The trends of the colour change of the youthful samples and elderly samples from pre-colouring to post-colouring were analysed and compared with that of the colouring effect of the mineral hair colour (See Table 1).

Results & Discussion

In terms of the feasibility of the recipe, the results of Experiment 1 showed that the use of a herbal hair colour formulated with vinegar and black beans was able to colour youthful grey hair samples and elderly grey hair samples to a darker colour. This as the result of decocting vinegar and black beans and the black pigment in the black beans was dissolved, extracted, and applied to the hair samples to achieve colouring results. The results of Experiment 2 showed that mineral hair dyes using limestone and hufen were equally capable of colouring young grey hair samples and old grey hair samples darker. This was the result from the interaction of lime with the hair to produce sulphide, which then interacts with hufen to produce black lead sulphide which achieved the colouring effect (Yang and Feng, 1998).

As for the colouring effect, the experimental results showed that the colouring effect of the mineral hair colours was better than that of the herbal hair colours (See Table 1), with good colour fastness, stable colouring effect, and inconspicuous colour fading. While the herbal hair colours showed obvious colour fading and poor colour fastness but were still able to colour at 18 hours after colouring. For example, at 18 hours of colouring, the youth samples with mineral hair colours appeared dark brown, while the youth samples with herbal hair colours appeared brown with localised light brown hair segments. At 18 hours of colouring, the elderly samples with mineral hair colours had a dark brown colour with the presence of brown in the layout of the hair, while the elderly samples with herbal hair colours had a light brown colour.

When using the same type of hair colour, the colouring effect varies according to the age group of the coloured samples, and in the case of herbal hair colours, the colouring effect of youth samples is better than that of elderly samples. In combination with microscopic observation, at one hour of colouring the youth samples appeared light brown with the local presence of dark brown colour segments. Whereas the elderly samples appeared light brown at one hour of colouring. At three hours of colouring, the youth samples appeared brown, while the elderly coloured samples were light brown, faded, and had brown spots attached. At 18 hours of colouring, the youth samples appeared brown, while the elderly samples appeared light brown at 18 hours of colouring. In the same way, the mineral hair colours also showed similar results, for example, at 18 hours after colouring, the youth samples were dark brown in colour, while the elderly samples showed uneven colouring, with most of them being dark brown and a few were partially brown.

Thus, it can be seen that the ancient Chinese hair colours are authentic and trustworthy, and people from different age groups can colour their hair according to the recipes. Combined with the fact that hair related cosmetics have been found in a number of tombs, as mentioned earlier, it may be possible, on this basis, to reflect on the possibility that substances stored in cosmetic boxes or other utensils found during archaeological excavations had the potential to be used as hair colours or had the function of colouring the hair. For example, lead powder excavated in the course of archaeological work belongs to the same category as that used in mineral hair colours, and perhaps, in addition to being used in daily make-up of the past despite its toxicity, it can also be used as part of the hair colours, mixed with other recipes and used in conjunction with other tools for colouring hair. Meanwhile, the spiritual world reflected by hair colours is also worthy of attention. Different groups of users may have turned their hair grey for genetic reasons, ageing, or other factors. Out of the aesthetic concept of ‘black hair symbolises beauty’, they used hair colours to change the colour of their hair from white to black, which illustrates the ancient people’s quest for beauty and youth, and made use of herbals and minerals that appeared in their lives to colour their hair.

Conclusion

As far as Chinese hair colours from the Jin and Tang Dynasties are concerned, due to the fact that few archaeological discoveries of Chinese hair colours have been made, only historical sources can be relied upon to speculate on the preparation and colouring process at that time. Experimental archaeology builds a bridge between ancient cultural relics and the life of modern society, and by designing and carrying out experiments with herbal hair colours and experiments and mineral hair colours after analysing a systematic understanding of ancient hair colours, it helps to discover phenomena of archaeological discoveries that may have been overlooked.

The reconstruction process involved a lot of experimental factors, such as the type of hair colours and the materials used to colour the object, to observe and discuss the authenticity and feasibility of ancient hair colours. Experimentally prepared herbal hair colours and mineral hair colours can colour grey hair samples from youth and elderly people. In terms of hair colours, mineral hair colours give superior results to those of herbal hair colours. In addition, different age groups of grey hair samples also have an impact on the colouring effect, with youth samples having a better colouring effect than elderly samples when using the same type of hair colour.

The hair colours involved in the experiments are only a small fraction of the herbal hair colours and mineral hair colours used in the Jin and Tang Dynasties. More experiments need to be carried out to fully recreate the full range of ancient hair colours. The experimental reconstruction of ancient hair colours focuses on reproducing the preparation and application of ancient herbal hair colours and mineral hair colours as much as possible through historical sources, in the hope that it will serve as a precursor to the remains of hair colours, which were often overlooked during previous archaeological excavations.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Baoding University Research Cultivation Fund, Project No: 2022D04.

- 1Three years in Chinese context means a long duration, not a specific period of time!

Keywords

Country

- China

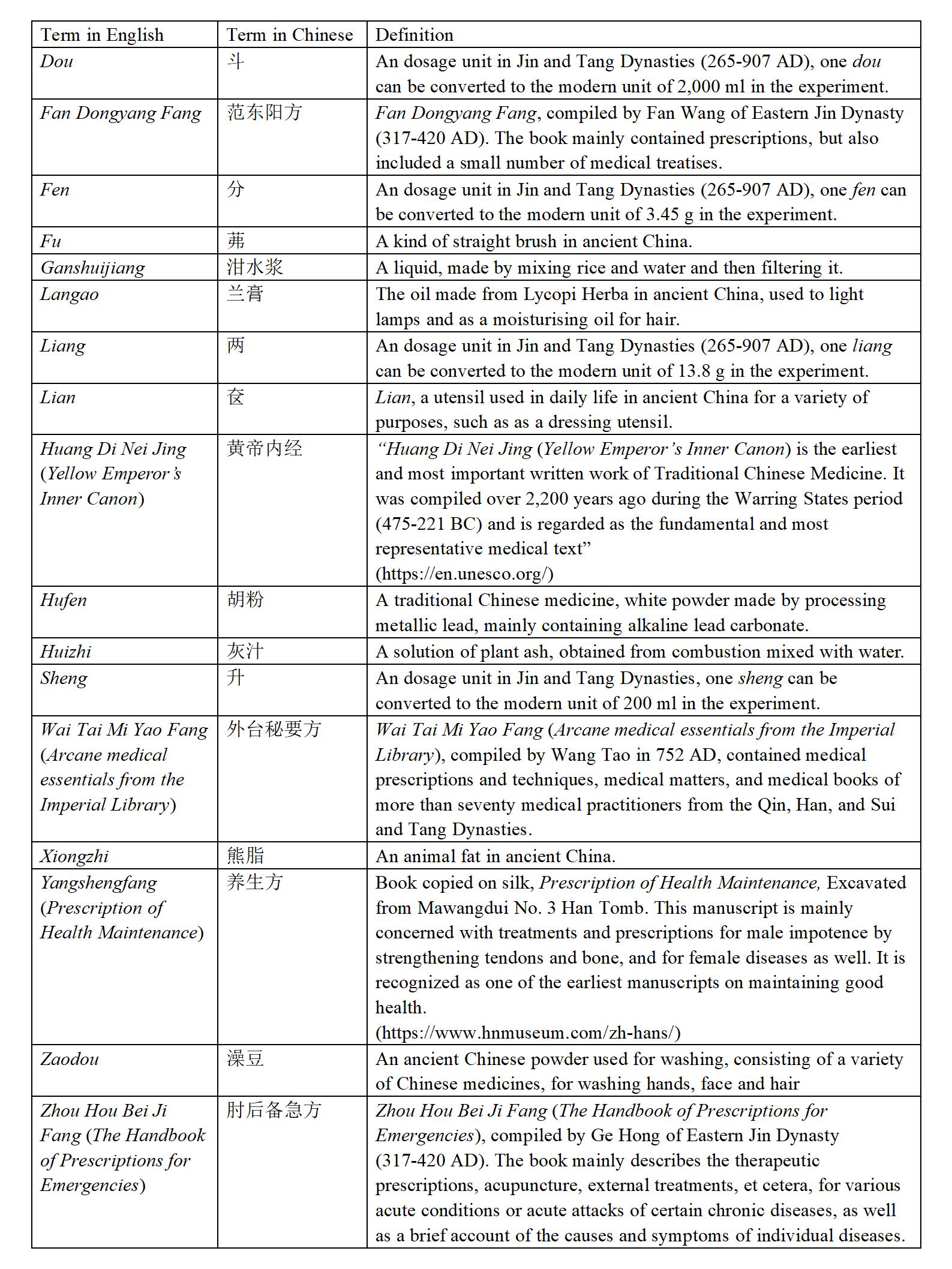

Glossary

Bibliography

Ban, G., 1962. Han Shu. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.

Fan, W. Fan Dongyang Fang. Fan, X., ed. 2019. Beijing: Publishing House of Ancient Chinese Medical Books.

Fang, Y.L. and Zhang, D.B., 2004. Wai Tai Mi Yao Fang dui zhongyi fangjixue de gongxian. Modern Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2, pp.51-55.

Ferrari, E., Mercier, F., Foy, E. and Téreygeol, F., 2021. New insights on the interpretation of alum-based fake silver recipes from 3rd century CE by an experimental archaeology approach in the laboratory. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 36(April 2021), article number: 102742.

Ge, H. Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang. Shen, S., ed. 2016. Beijing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine Co., Ltd.

Hao, H.B. and Liu, S.M., 1998. Further Discussion on Medical Significance of Wai-tai-mi-yao. Chinese Journal of Medical History, 28, pp.246-248.

Kong, F.D. and Zhang, H., 2017. Chinese traditional hairdressing and its cultural connotation. Journal of Clothing Research, 2(2), pp.178-182.

Qiu, G.M., Qiu, L. and Yang, P., 2001. Measurement Volume Science and Civilizations in China. Beijing: Science Press.

Qiu, X.G., 2014. Changsha Mawangdui Hanmu Jianbo Jicheng. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.

Tang, B.C., 2023. Discrimination and analysis of the difference between experimental archaeology and laboratory archaeology. Journal of Baoding University, 36(1), pp.40-43.

Hunan Provincial Museum and Hunan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, 2004. Tombs 2 and 3 of the Han Dynasty at Mawangdui, Changsha, Volume 1. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press.

Wang, T. Wai Tai Mi Yao. Reprint 1955. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House.

Wang, F.Y., 2015. Handai Huazhuang Yongju Shixi. Master’s dissertation. Northwest University (Xi'an, Shaanxi, China).

Wei, Q.P. and Hu, X.H., 1992. Mawangdui Hanmu Yishu Jiaoshi. Chengdu: Chengdu Chubanshe.

Wu, S., Huang, X.L., Ye, X.L. and Ye, X.M., 2022. Origin and development of external treatment of gray hair with traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, 46(1), pp.109-112.

Yang, B.Y. and Feng, Y.H., 1998. Shihui shiliao chutan. Geology of Chemical Minerals, 20(1), pp.55-60.

Yang, L., Fu, Y.L. and Zhang, L., 2012. Research on Asarum herb dosage of herbal decoction in Waitai Miyao. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, 27(4), pp.969-972.