The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

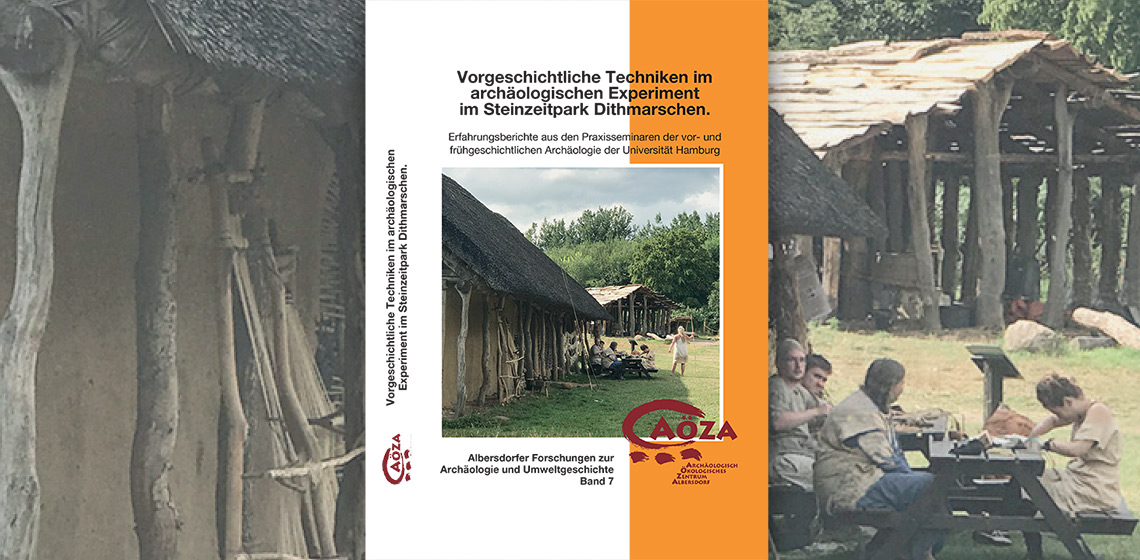

Book Review: Vorgeschichtliche Techniken im Archäologischen Experiment im Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen by Rüdiger Kelm and Birte Meller (ed.)

The Archaeological Institute of Hamburg University has been offering courses to students in the field of “Experimental Archaeology and Museum Pedagogy”, for over 15 years. These courses take place annually at the Archaeological/Oekological Center Albersdorf (AÖZA).

The AÖZA is an open air museum just outside Hamburg, providing all the space and resources necessary for students taking their first steps in the world of prehistoric techniques. Over the years both institutions developed a fruitful collaboration, which lead to numerous recorded experiments, of which 20 were selected by a students´ editorial board and have been published in the present book.

Since the rediscovery of experimental work in German archaeological research at the end of the 1980s, countless attempts of recreating ancient crafts were made. It took some time until this method of exploring the past was certified by a thorough method critique, thus establishing standards as they apply for scientific experiments. It is remarkable and very much appreciated that all experimenters at the AÖZA were well aware of these standards and started their projects by posing a clearly defined question. This is surely to be attributed to the self-conception and experience of the initiators of these courses, Tosca Friedrich and Birte Meller, whose intention it was from the beginning to elicit the dust-dry German archaeology from the ivory tower it caged itself after the Second World War. So the experiments described here are well beyond the step of “just trying”, even if the results were not sensational and did not change the world. However, in most papers the following statements are often seen (and experienced in similar courses I personally delivered to students) “During my work I gathered a lot of knowledge and am conscious now how time consuming producing even simplest things with my own hands is, if I use prehistoric techniques”. This experience alone is worth every trial in making nets, shoes and ceramics, no matter how scientifically these projects are documented, because it enables the experimenter not only to talk about but to talk of something. This ability is a good base not only for scientific work such as interpreting an archaeological find or record but also for educational work in a museum. Moreover, it empowers future archaeologists to question their view of things and encourages them to maintain the connection between hand and spirit, manu et mente.

Therefore, it is not essential that in advance of making a fishing net it is recommended to ask a fisherman (he would have informed the experimenter to use a stencil made from wood or bone in order to braid regular meshes), nor that it would make a great difference if one used bone for carving Ice Age art objects instead of mammoth ivory, because the two materials have quite different properties as for their workability and hardness. The main thing is the physical experience and the insight that Experimental Archaeology gives – whether a technique does work in a certain way or not. I am sure that if some of the authors conduct further experiments in the future, they will have at hand the tools of the trade necessary for good scientific practice.

Reading the book was an entertaining pleasure, very often reminding me about my first experiments I made decades ago with all the trials and errors described here. I hope that Hamburg University and Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen will be retain the opportunity to continue this project for many years.

Book information:

Vorgeschichtliche Techniken im archäologischen Experiment im Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen

Erfahrungsberichte aus den Praxisseminaren der vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie der Universität Hamburg Albersdorfer Forschungen zur Archäologie und Umweltgeschichte, Bd. 7 Hrsg. by Rüdiger Kelm und Birte Meller. Archäologisch-Ökologisches Zentrum Albersdorf (AÖZA). Husum Verlag

Pages: 181, Price: € 17,95

ISBN 978-3-96717-070-2

Country

- Germany