The content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

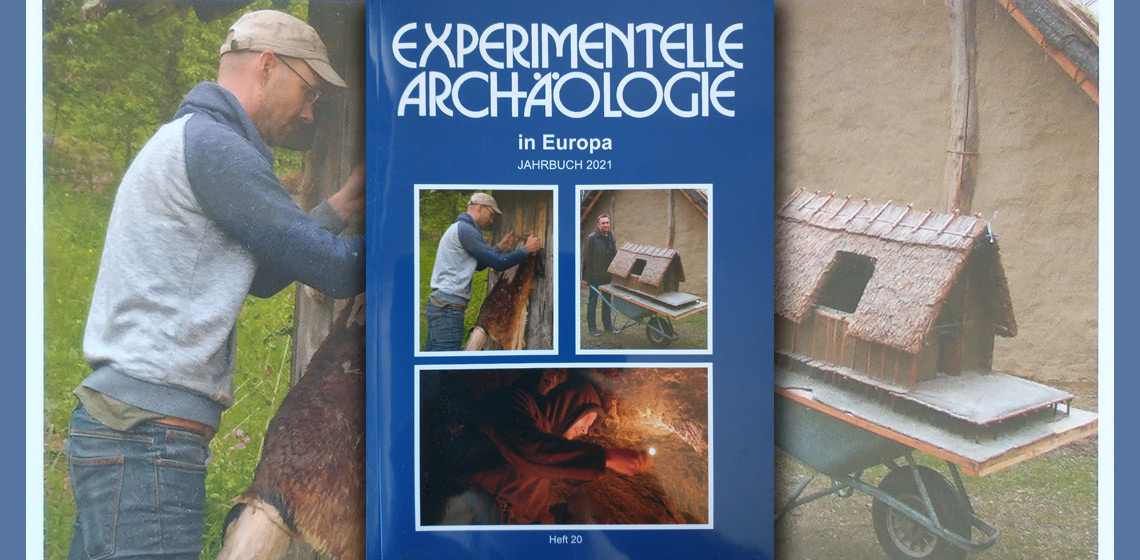

Book Review: Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch 2021

The periodical (Jahrbuch) was published by Gunter Schöbel and the European Association for the advancement of archaeology by experiment e. V. (Europäische Vereinigung zur Förderung der Experimentellen Archäologie) in collaboration with the Pfahlbaummuseum Unterhuldingen.

This volume – like many in the last two years – has been affected by the pandemic and EXAR waived the fee for many of the affected members. As always, the periodical is divided into three parts: Experiment und Versuch (experiment and testing, pp.10-78), Rekonstruierende Archäologie (reconstructive archaeology, pp.80-101) and Vermittlung und Theorie (communication and theory, pp.103-194). Towards the end there is a report on the EXAR-Projekt Den Erzen auf der Spur (pp.196-209) written by Ch. Helmreich, F. Kobbe and M. Sauerwein. The project looks into “identifying the original ores for bloomery furnace slags from an archaeological site in Lower Saxony” (p.196). The last two “articles” are an addendum to a previously published article: Nachtrag zu “Der Transport der Stonehenge Steine” by A. Braune which was originally published in Heft 18, 2019 and a short report by J. Goll and H. Stadler on ceramic balls found at Burg Rotund and Schloss Tirol (Keramikkugeln - Steinbüchsen und Leonardo da Vinci – Die Bombarde aus Runkelstein in Geschichte und archäologischem Experiment, p.213-215.)

The periodical contains a great variety of experiments. An example is the reconstruction of an ancient linen cuirass as part of the Hamburg Linothorax project (M. Zerjadtke, T. Kasperidus, Zur Konstruktionsweise des antiken Leinenpanzers, pp.27-47) of which some results are presented. The experiments demonstrated that not all reconstructions need glue to be effective against weapons. Another experimental archaeological study related to mining lamps from Schwaz-Brixlegg (J. Hass, D. Jaumann, R. Lamprecht, V. Tsiobanidis, D. Turri, Experimentalarchäologische Untersuchungen zur Herstellung und Verwendung von spätmittelalterlichen/frühneuzeitlichen Grubenlampen aus dem Bergbaurevier Schwaz-Brixlegg (Tirol/Österreich), pp.48-66) where the lamps were reconstructed and tested in their original environment, with researchers even wearing reconstructed clothes that miners at that time would have worn.

The section on reconstruction contains three articles, two by the same author, Anne Reichert. In the first one, Experimente mit Birkenrinde. Versuche zum Herstellen von stabilen Gefäßen (p.80-87), she shows how Stone Age birch bark vessels are made. To be able to work with the bark, it needed to be soaked in water to guarantee flexibility. The reconstructions are not, however, of the same size as the archaeological evidence (p.82), and it is not made clear why the reconstruction was made. Her second article, Rekonstruktion einer Sandale mit Lasche (p.88-90) is based on the archaeological find of a sandal from Switzerland. She reconstructed the sandal with lime bast and provides beautiful images of the various steps undertaken. The last article in the reconstruction part is written in English, Experimental reproduction of the so-called “Galassina” Etruscan mirror by S. Pedron and F. Fazzini (p.91-101). The authors guide the reader through their very thorough reconstruction of the mirror. It is based on an archaeological find from the “necropolis of Castelvetro – Modena, Italy” and can be dated to the end of the sixth, middle of the fifth century (p.91). Through their experiment, they could prove that some decoration was added as early as the wax model stage while others were “obtained by cold working” (p.100).

The first article of the periodical looks at the hazelnut as a potential tanning agent in the Mesolithic period (M. Klerk, Ein mesolithisches Superfood als potentieller Gerbstoff? Experimente zum Herstellen von Leder mit dem Fett der Haselnuss, p.10-26). The hypothesis is that the ‘superfood’ hazelnut could also be used for leatherworking. However, there has been no archaeological evidence to support that theory (p.14). Plenty of remains of hazelnut have been found on archaeological excavations, which led to the idea in the first place, however, it would appear to be a modern point of view to use plant-based fats instead of animal fats for tanning work. The author looks for sources in ethnology that use plant-based fats for tanning, but does not seem to consider the difference in time. The experiments with the hazelnut fats are logical and the results prove that it was possible to use the fat of the hazelnut for this purpose, but only when other fats were added in the process, does it show the same results as tanning with animal fat.

One thing that was striking was the “gendering” of words which is currently very “in” in German. Apart from it being not correct grammatically (and the periodical itself mentions on p.217 that authors should follow the guidelines of the “Reform der deutschen Rechtschreibung” from 1998), it is also not done consistently throughout. The preface uses “AutorInnen” whereas many authors opted for the “Autor*innen.” The so-called gender star (Gendersternchen in German) or asterisk is placed between the stem and the feminine suffix of the word to refer to all genders and non-binary people. This way of trying to include people of any gender interrupts the reading of the texts and feels forced and “woke” instead of inclusive. It is heavily debated in Germany and does not agree with the rules of German orthography. A similar impression was left by the article by M. Siegmann Stoffe, gelb -Safran (pp.68-78) in which the language used distracted from the interesting content of the article about saffron as a dyeing agent for textiles. The style did not resemble general academic writing, e. g. “Und nein, Gestank und Bäh waren den Leuten nicht egal “(p.73, translated into English: “and no, people cared about the smell and eww”) and the grammatical choice of not using the article made reading the text difficult, e. g. “allerdings war Verfasserin beim Lesen […] verblüfft” (author was surprised) (p.69). This requires a definite article “allerdings war die Verfassering beim Lesen […] verblüfft.”

The last part, Vermittlung und Theorie (communication and theory) contains five articles in total. P. Walter looks at Neolithic stone gouges in his article Neolithische Steingeräte mit Hohlschliffklinge (p.103-118). What started as archive work for the Pfahlbaumuseum Unteruhldingen turned into a search for similar objects all around the world with the suggestion of an experiment to reconstruct the gouges to show their various usages. W. F. A. Lobisser introduces a house model, reconstructed based on a model from a prehistoric find from Hornstaad (Bodensee) with a didactic function in his article Archäologische Vorbilder für Architekturmodelle in Hinblick auf die Entwicklung eines neuen idealisierten didaktischen Hausmodells zur Pfahlbaukultur nach einem prähistorischen Befund von Hornstaad am Bodensee, (p.119-142). With a short introduction to the history of architecture models, the criteria they need to follow to gain the title “reconstruction” and how archaeological evidence helps, Lobisser explains the choices for “his” didactic model. Based on an archaeological find, the didactic model is more flexible in how it is put together by those using it. It offers the possibility of more than one interpretation. The fact that Lobisser is aware of this, as he describes it in detail, makes this an interesting object to work with. M. Baumhauer looks at the Iron Age ‘Doppelpyramidenbarren’ and its meaning, basing his article “Doppelpyramidenbarren” – eine eisenzeitliche Barrenform und ihre Bedeutung (p.168-181) on the master’s thesis of Ch. Nock (p.168). He looks at the research history, the find spots, the find context as well as how they were found. The last article of this group, Rekonstruierende Archäologie und Vermittlung im EU-Projekt PalaeoDiversiStyria am Universalmuseum Joanneum in Graz (p.182-194) describes the EU Project PalaeoDiversiStyria which is a a project between Austrian and Slovenian partners. “The main aim of the project […] was to support the understanding of cultural heritage and agricultural, gastronomic and craft traditions of the border region between Styria and northeastern Slovenia” (p.182). One of the results of the project was the creation of the brand “Heriterra” (heritage and terra, p.183): this brand supports quality food and craft products which use archaeological and historic role models for their products.

My personal favorite was the article by G. Schöbel, Nachbildungen archäologischer Funde als Lehrmittel für Museen, Universitäten und den Schulunterricht in Deutschland in der Weimarer Zeit (1918-1933), p.143-167. The history of teaching aids and teaching collections have not been on my mind previously, even though I had the “luxury” to work with teaching collections during my time at university and work experience. Schöbel manages to paint a beautiful picture of the history of teaching aids and teaching collections. Especially the story and history of teaching material publisher F. Rausch is presented vividly (p.156-162). Interestingly, many of the materials created by Rausch that were once meant to be teaching aids due to the lack of original archaeological artefacts, have now become valuable museum pieces themselves. The article is a lovely discourse in favour of physical teaching material in schools and museums.

All in all, the periodical provides a broad overview of experimental archaeology and offers a nice overview of various subjects within the field. It presents studies and experiments that were carried out with a passion for archaeology and history at the same time.

Book information:

Schöbel, Gunter (ed.), 2021. Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch 2021, Heft 20, Unteruhldingen: Gunter Schöbel & Europäische Vereinigung zur Förderung der Experimentellen Archäologie e.V. European Association for the advancement of archaeology by experiment, ISBN: 978-3-944255 – 19-4.

Keywords

Country

- Germany