The content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

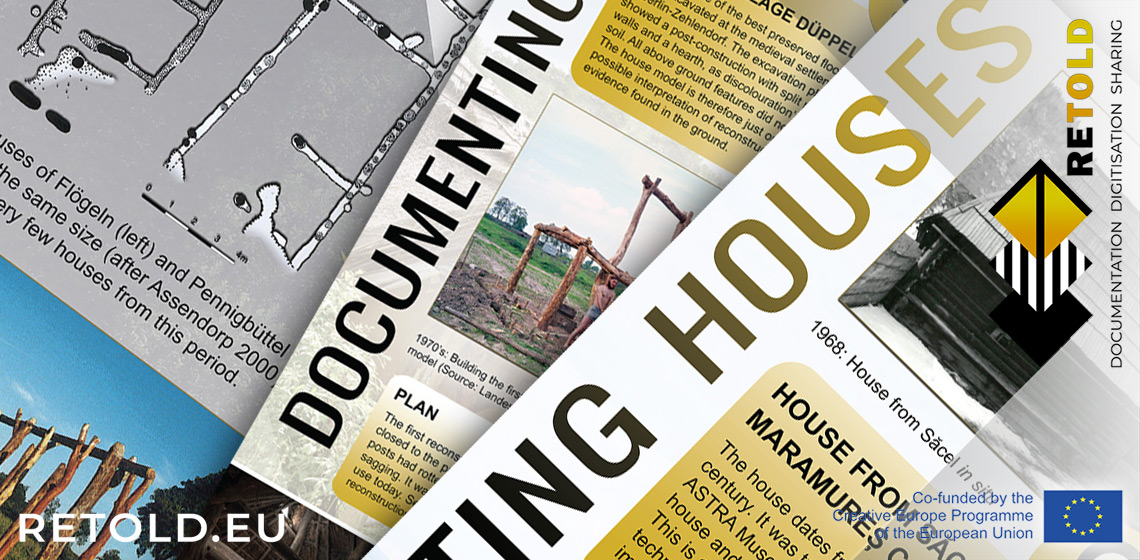

RETOLD: Documenting Houses, Sharing the Story with the Visitors

Open-air museums host much cultural heritage data. You can find them in archival records, photos, video, and the minds of people. These data are at risk of being lost. This is where RETOLD comes in, a European Project (Creative Europe Program) with six partners working together on a solution.

Exhibition

There are different way of storing and sharing data. One is developing a platform where museums can store the information in an ordered way. Another way is to show what we are doing to the public and stakeholders. We decided to create an exhibition made of banners with samples from three museums. Each partner can show houses and later crafts, and explain how they are documented in their museum. In this way, we also share all the work behind the scenes with the visitors, including what we find is important to preserve for the future generations.

While in 2022 we made banners that dealt with general principals, in 2023 it was time to start working on the main aspect of the project, which is Documenting Houses. Each partner selected one house either built based on an excavation (archaeological open-air museums) or an original building translocated from a different location to preserve it (historical open-air museum / skansen). The banners were prepared in English, but can be in any language at request.

Following five simple questions, we made the storyboard for each house:

- What is the house based on, where does it comes from and what is it?

- reconstruction / rebuilding

- (possible) plan of the house

- final product and its use

- some special details

Depending on what house is selected and its provenance, the order can change, but all those five elements are well represented. For each part of the story we designed icons which can also be used later in the online version for the same subjects.

The Choice

It was interesting to see which house each museum selected, and why. Was it because they had enough information about it available, or was that house significant to the museum? In two cases, we show the history from the 1960s through 70s, 90s and present times, while one house was only excavated in the late 80s, and so shows the reconstruction from the 90s and its rebuilding by the end of 2019.

See Figure 1: “House 14 was chosen as a pilot study on new workflows for standardised documentation as part of the EU project RETOLD, as the excavation results showed it to have the clearest features of all house plans. The split plank walls are clearly visible, as are the main posts as well as the fireplace. The first reconstructive house model was built in 1974/5, it had to be re-built in 1999, as the roof construction had started to sag. The main posts were re-used from the original construction, although the rotten material was cut off so the re-used posts were shorter. The construction is yet again in need of being re-built. Preparing the taking down of the house, as well as the new construction of a house model, is another reason, why this house was chosen as a pilot for digital documentation.”

Julia Heeb, Museumsdorf Düppel - Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin (DE)

See Figure 2: “The “House of Pennigbüttel” is one of the best excavated and documented houses of the middle Neolithic Era in Northern Germany. Another reason was the unusual ground plan with three basic posts which allow reconstructing the roof with a heavy grass roof.”

Rüdiger Kelm, Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen (DE)

See Figure 3: “The House from Săcel, Maramureș County was chosen because it is one of the first transferred houses to our museum. It is a house that represents the knowledge of some of the best wood artisans from Romania. It is well documented from the late sixties of the last century.”

George Tomegea, Complexul National Muzeal ASTRA (RO)

The Images

As usual when talking about the technology from before digital times, the images were scanned at some point, and not always at highest resolution and were often very pixelated. One may ask why they chose to do so; was that due to the lack of proper equipment or lack of knowledge about digital images and the resolution? One issue, which is popping up more often lately, is the choice between scanning an old photo, or taking a photo of it. The answer is to always scan if you can.

There are many tricks about how to scan old images, and the internet can tell you all about them. For example to avoid pixilation, you can turn an image 45 degrees, and only turn it back later in a photo editor – advice from the late 1990s. There are also many tools available to correct scanned images.

Resolution is a larger problem. Most people do not understand resolution, and the consequences of low or high resolution. Why not pick the highest resolution when scanning? Why not set your camera to the highest resolution possible when taking a photo? You can always downsize an image, but making it higher resolution is impossible.

Most of the current cameras are 24 megapixels (even on your phone). When we take a photo with a 24-megapixel camera, these can be about 6000 x 4000 pix. If you apply a resolution of 100 dpi, you will get a 150 cm wide image (for a poster / banner 100 dpi is a minimum, as you observe it from a distance). If you use 300 dpi (high quality print), you will have an image of 50 cm by 30 cm. The best option is to save in RAW format, but for that, you need somebody who is good with editing software and has enough storage space. Otherwise, Tiff will do very well, and JPG is fine.

When we take those images or make the scans we need to think about the future, technology is changing fast, and what is OK now, in 10 years will be old school. So think about your successors when taking a decision now about how you digitize the images you have. Keeping all your archive on the server, making them digital, saves much space in your physical storage. If you do have a chance to digitize your old photos and drawing, please do.

One extra word of advice: label and tag your images properly, with date, name and keywords, so you can easily sort them. There are also different ways to store your images, but that is a subject for another article.

The Drawings / Plans

Designers like to have drawings and plans as vectors, and not pixels. This requires another way of drawing and storage. This is not always possible, but it gives you an opportunity to make them as large as you want without losing on quality. Saving as PDF also enables you to keep sharp lines, and text linked to it. It requires that you use proper settings when saving as PDF, but that will also give you more options in the future. In addition, the files take little storage space. What is nice about those drawings and plans is that when saved correctly, you also have the ability to easily remove the background, and just have a line drawing.

The Text

When designing the banners, the choice of words explaining the images is important. Authors often do not keep their target group in mind when writing text. What helps is making a storyboard as we did with the banners. This pushes you to make a decision about what story you tell and how. Who is going to read this story? How long will they look at the banners? The banners are just a teaser; the rest is told inside the museum or through other publications or the website. Therefore, it is important to try to make it interesting, but succinct. People may want to know why you rebuilt the house after 20 years. Moreover, you might want to givea different explanation to the public than for your colleagues from other museums, but it’s important to be honest.

Keep in mind that the visitors believe things they see to be true; it is the responsibility of the museums to share the most likely version of events and to make it clear that what you display is just one of the options. Think from the user perspective, and following the five questions asked before, give the best possible answer, an answer which is understandable for both a schoolkid of 12 and a senior of 75.

For original houses, story is very important as well. Why is this house so special that you saved and translocated it from its original location into the museum? How often does it need repairs, what story can you tell about it? Do you still use it in its original function?

In both cases the public wants to be involved. Can they actually step into that house, and try things out? What other information will they find there? Manage their expectations.

Conclusions

This was the first time we did this kind of “exercise”. I believe the results are very good, partly thanks to the fact that all people involved were senior in their jobs and experience. Combining different backgrounds and expectations is always interesting, and when working within a frame of a European Project, it is the most challenging but also most rewarding part of the job. Showing what we have in common in different areas of Europe makes it possible to make our stories last longer and keep our heritage alive.

The banners are at the ASTRA Museum in Sibiu, Romania, the Steinzeitpark Dithmarschen and Museumsdorf Düppel, both in Germany. If any other museum is interested in this concept and would like to show or document their houses as well, please contact EXARC.

Keywords

Country

- Germany

- Romania

- Spain

- the Netherlands