The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

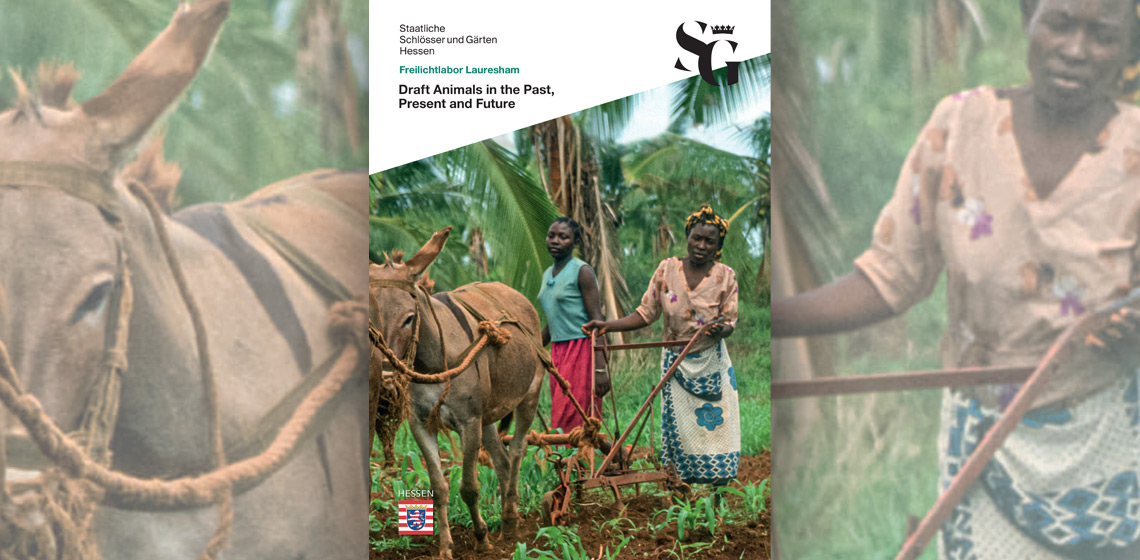

Book Review: Draft Animals in the Past, Present and Future by Claus Kropp and Lena Zoll (eds)

The domestication and subsequent training of strong animals to pull vehicles was a game changer for humans. Just like the first person who jumped onto a horse and hung on as they veered giddily towards a new horizon, driving and draft meant that humans got places faster – goods could be stored in a vehicle for longer journeys, trade goods became more than what a human could carry on their backs, and land could be ploughed faster and further. Horses, donkeys and oxen have literally hauled humanity into economically successful societies. Nor is the draft animal a creature of the past: developing nations employ animals in the same way as earlier societies (Davis 2021). For those of us interested in human and animal relationships of the past this text, which is the proceedings of a digital world conference in 2021, is a welcome addition to the small corpus of work on the practicalities of domestic working animals.

Starkey and Mudambari (9 to 29) make a vital and often overlooked point – that draft animals are linked intrinsically to cultural identities. Think of iconic images of 19th century British Shire horse teams, decked in brasses, pulling the plough; trains of pack camels laden with spices and silks, trudging across the sands of the Silk Road, or doe-eyed and huge-horned oxen pulling carts, depicted on Egyptian tomb friezes. This use of draft animals as heritage motifs is also highlighted in Witold Wołoszyński and Julia Hanulewicz’s delightful chapter (113-123) on the use of draft animals in the National Museum of Agriculture and Agri-Food Industry in Szreniawa, Poland. Their enjoyment of displaying traditional agricultural practices is positively infectious, and I admit that it is something I have now placed on my bucket list.

Looking at past societies and human relationships with their draft animals allows Bob Powell (71-79) to bridge issues of heritage with practical horse care, with his fascinating discussion on the Scottish Farm Horseman’s Society during the age of horsepower. We see confraternities of farming folks dedicated to equine care creating a club with its own often-mischievous rites and initiations which is, arguably, a valuable lesson for archaeologists to remember that ritual is not necessarily a sombre thing invoking high magics – it is often a means to express belonging to a profession, activity or region.

The theme of draft animals and equipment as tangible heritage continues with Claus Kropp’s personal reflections on the use of oxen in Living History Museums (123-137), Barbara Sosič’s exploration of how draft animals are presented in historical narratives (113-123) and Andrew B Conroy’s (137-153) examination of traditional teams of oxen being used at fairs and rural events in the United States. People love to see animals and humans combine to re-enact history, making such displays ready crowd pleasers, which have the bonus of educating on animal husbandry, ancient methods of farming, associated maintenance crafts and agricultural practices. An important point made by Klopp is that ancient harness fittings were not always kind to the animal, so the equipage can be made to look authentic but compliant to modern animal welfare standards, to not cause distress to the animal – simulations rather than exact replicas.

More abstract ideas of connectivity between animal and human are examined by Peter Moser (129-137), although there is considerable naivete in his idea that “work itself was always done in cooperation between human beings and animals” (page 130). The animals involved had no choice in the matter. We know that draft animals were all too often used as machines rather than sentient beings from the Industrial Revolution onwards, leading to Victorian charities addressing animal welfare systematically, for the first time (Bates 2018) however the ancient world also has considerable evidence of both neglect and wilful cruelty (Bartosiewicz and Gál 2018). It does, however, prime the reader for subsequent chapters which deal with the use of draft animals, to highlight the triple themes of welfare, heritage and using traditional knowledge to make a sustainable future.

Rosenstock (45-63) ably discusses the creation of the revolute joint in prehistory, which allowed chariots and vehicles to be made – there are echoes of this in Marcel Scheidweiler’s (87-95) narrative of making home-made breastplates for donkeys in Burkino Faso, to ensure both efficient driving and the welfare of the animals. In its own way, it is a modern example of revolutionising how people interact with and employ animals. Paul Schmidt (165-177) looks at a different kind of modern revolution – using horsepower in small scale modern farming as an environmentally friendly option, something which is again discussed by Rodriguez (211-217) and Thomas (191-197). This awareness of past peoples getting some things very right, then updating their methods of draft to address the concerns of the 21st century is echoed in H. S. Sanhueza Leal et al’s (165-177) contribution, using high-tech methods on small scale tilling in Columbia. Sustainability via learning from the farmers of the past is again the theme of Antonio Perrone’s paper (185-191), advocating draft animal power to be (re)considered as an efficient tool to stimulate development.

There is much here for the experimental archaeologist interested in ancient economies and animal husbandry, but there are equal benefits for those interested in animal welfare in developing countries, and for environmentalists looking for more sustainable ways to farm. Heritage, of course, is the bond between these themes. The text is open access, and has enough interesting papers to appeal across a wide audience in various disciplines.

Book information:

Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Hessen, Kropp, Claus and Zoll, Lena (Eds.): Draft Animals in the Past, Present and Future, Heidelberg: Propylaeum, 2022. https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.1120

Keywords

Bibliography

Bartosiewicz, L and Gal, E. 2018. Care or Neglect? Evidence of Animal Disease in Archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Publications

Bates, A.W.H., 2018. A Spark Divine? Animal Souls and Animal Welfare in Nineteenth Century Britain’ in Linzey A and C (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Animal Ethics London: Routledge, 361-370.

Davis, T. 2021. ‘Harnessing Horse Power: Then and Now’ in Maguire, R and Ropa, A (eds) The Liminal Horse. Budapest: Trivent. 177-196