The content is published under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

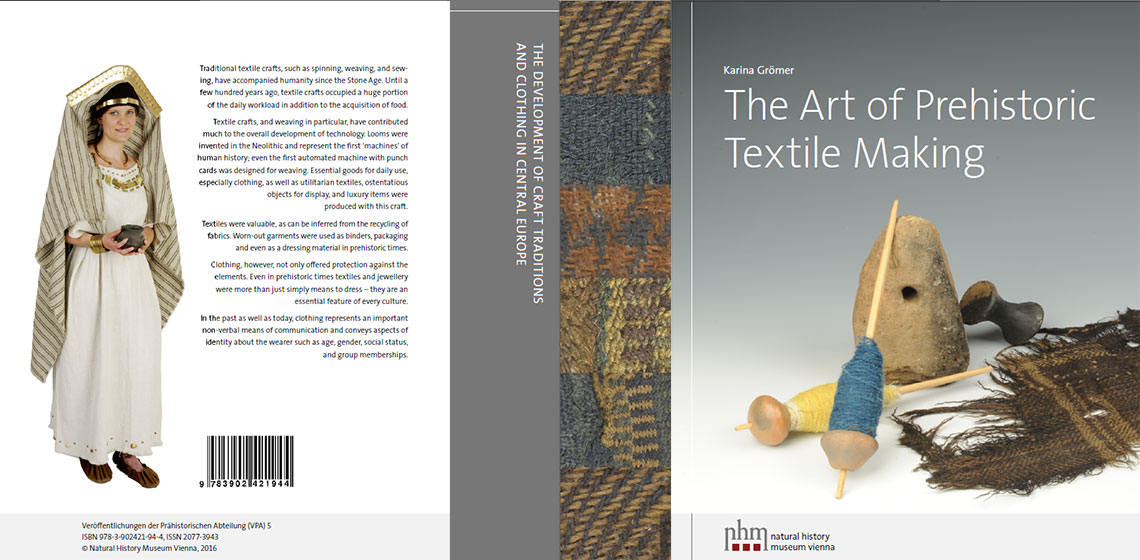

Book Review: The Art of Prehistoric Textile Making: The Development of Craft Traditions and Clothing in Central Europe by Karina Grömer

Textile research has made significant advances in recent years as new technologies and methods are developed, tested, and applied to the analyses of archaeological textiles. The FWF-Project1, a collaborative research effort involving researchers and artists from institutions in Austria, the Netherlands, and Germany, engaged in a four-year effort during 2008-2012, to examine dyeing and fabrication techniques used in the production of prehistoric textiles from Austria and neighboring countries. A number of publications and exhibits resulted from this groundbreaking body of work, including this ambitious book version, the subject of this review, which includes more recent research and additional finds, such as the Iron Age Hammerum Girl textiles.

Historians, costume designers, archaeologists, and anyone interested in handwork, artisanship, and the history of costumes and crafts, are the author’s intended audience for this book. Written from the perspective of a prehistoric archaeologist in an effort to illuminate Central European prehistory, the major concern of the book is to distinguish the process of refinement in textile technologies, beginning with the first early agricultural societies of the Neolithic, continuing with a wave of innovations noted during the Bronze Age, and finally the further refinements observed during the Hallstatt period.

The introduction begins with a survey of technology, along with cultural, social, and economic developments occurring during the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages in Central Europe through the lens of prehistoric research. This is followed by a section on the fundamentals of textile preservation, and finally with a consideration of defining textiles within the context of this project, focusing on woven goods and the processes involved in their production. Where relevant, basic concepts and methods associated with prehistoric archaeology are briefly explained.

The second chapter, Craft techniques: from fiber to fabric, covers the full range of processes and techniques involved in the manufacture of prehistoric textiles from available plant fibers (flax, hemp, stinging nettle, tree bast) and animal fibers (sheep wool, goat and horse hair, wild game hair). The section concerning textile dyeing, which considers colouring agents and the processes of dyeing, is based on extensive research done with the Hallstatt mine textiles, and includes an informative overview of the scientific methods used in investigations of textile dyes (liquid chromatography and microscopy), as well as other recent developments in technologies used to analyze textile dyes. Archaeological evidence for the use of organic colourants -- plants, insects, shellfish -- is discussed, and demonstrated in an experimental setup with organic dyes and textile materials. Beyond the actual processing of fibers and production of cloth textiles, this section continues with a consideration of patterns and weaving decoration/ornamentation, finishing of wool and linen fabrics, and sewing and tailoring. While not intended for instruction as to the actual processes featured here, this section offers a solid demonstration of methods and technologies used in the preparation of fibers, processing wool, sample artefacts associated with prehistoric fiber preparation, spinning processes and technologies, weaving techniques and technologies, dyeing of textiles, and fabrication of clothing.

Beyond the methods and technologies of textile production, there is the context within which the ‘fabric’ of prehistoric social and economic systems develops. Here the author calls for a need to move away from a primitivist perspective when considering prehistoric textile craft products. The author states that one needs to consider levels of textile production, from those developing within the context of household production in the simplest form, to various stages of specialization and technological advancements, ultimately developing into systems of mass production. Household production of textiles never lost importance during prehistory. However, from household production developed household industries, eventually specialist production (with specialist skills and technology) and further workshop production, and ultimately large-scale industry for trade.

Graves and cemeteries, with burial garments and grave goods, adds another layer to the story presented through prehistoric textiles. In addition to burial garments and accessories, textile craft tools are often found as part of the assemblage of grave goods, revealing insights as to consumers, producers, division of labor, and sites of production. Addressing “craft sociology” (the craftspeople behind the textiles and places of production), further consideration is given to levels of textile production, the sociology of production, organization of labor, and places of production.

As part of a public outreach programme on ‘Iron Age Textiles’ at the Natural History Museum in Vienna, participants were asked their thoughts on the role textiles might have played in the life of prehistoric people. Clothing is the obvious first response. Beyond clothing, artefacts recovered from a variety of contexts reveal a broad array of technical and utilitarian textile items, such as wall hangings, cushions, household items, furnishings, sacks and bags for storage and transport, recycled materials used for binding, bandages, packing material, caulking, and elements used in the production of scabbards and belt linings.

Recovery of complete garments outside of the context of graves and cemeteries are rare. Assemblages of textiles and associated accessories and jewelry from burials or sacrificial deposits may not reflect everyday uses. Other sources of information, such as pictorial sources (including carvings and figurines) and written sources are helpful for interpretation of archaeological textile finds in terms of the history of costumes and clothing. While not intended as a comprehensive identification key, the section on Clothing in Central European Prehistory offers an excellent resource for reconstructions and curators, extending well beyond the intended focus of woven textiles to include shoes, headwear, jewelry, and including a discussion of clothing function (influence on the body, protection, identity, and social status).

In conclusion, textiles and textile production were, and are, essential throughout human history and prehistory, and is intimately associated with every level of society. This book provides an expansive view of the potential for textiles in the interpretation of past lifeways as well as for recovering preindustrial technologies used in the production of textiles. The shear volume of content included in this book begs for the publication of a series of more specialized and focused volumes for serious researchers and curators. The author more than delivers for the intended nonacademic audience, and provides the serious researcher with an enticing platform from which to launch further inquires in this fascinating field.

Book information:

GRÖMER, K., 2016, The Art of Prehistoric Textile Making: The Development of Craft Traditions and Clothing in Central Europe, with contributions of Regina Hofmann-de Keijzer (Dyeing) and Helga Rösel-Mautendorfer (Sewing and Tailoring), Veröffentlichungen der Prähistorischen Abteilung (VPA) 5, Vienna: Natural History Museum Vienna, ISBN 978-3-902421-94-4

Note: This review is of the digital PDF version available for no fee downloadable here.

Country

- Austria

- Czech Republic

- Germany

- Hungary

- Poland

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Switzerland

Bibliography

HOFMANN-DE KEIJZER, R. et al Coloured Hallstatt textiles: 3500 year-old Textile and Dyeing Techniques and their Contemporary Application, in NESAT XI ; The North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles XI ; 10-13 May 2011. Rahden/Westf: Leidorf, 2013. Johanna Banck-Burgress and Carla Nübold, editors. pp. 125-129.