The content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License.

Reviewed Article:

Resurrecting a Bog Dress: A Comparative approach to Medieval Textile Construction

In this article we recreated garment 38 from the fourteenth century garments preserved in a graveyard in Herjolfsnes, Greenland to explore the reasons behind the stitching techniques used. Using experimental methodologies, previous knowledge of patterning, and hand stitching techniques, we constructed one half of the garment using modern hand stitching techniques and the other using period techniques. We focused on the stitching, seam finishing, and tablet-woven edges, and evaluated each half on fit, drape, shape, and durability. Performing each step by hand allowed us the opportunity to become intimately acquainted with the medieval processes of construction and gain a better understanding of the experience of construction. Based on our final product, we concluded that the stitching techniques are particularly suited to make a sturdy and attractive garment from a relatively loose-weave fabric, allowing for the easy insertion of gussets and the performance of alterations and repair.

Introduction

Since natural fibres do not survive well in northern European environments, the lack of actual archaeological examples available to study makes the study of medieval textiles difficult. This makes the Herjolfsnes garments, intact garments preserved in a bog near a Norse village in Greenland from the 14th and early 15th centuries, especially important for our understanding of medieval northern European clothing (Roesdahl and Verhaege, 2011, p. 206). In investigating these garments, we were struck by the surprising choice of stitches used in the seams of the garment, specifically those outlined in Lili Fransen et al.'s Medieval Garments Reconstructed (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 28). This is important, as seams are not merely a part of a garment, but rather the central element which determines its fit and function. The seam construction in these garments was not typical of modern sewing methods, and we were interested to see what purpose this type of construction might serve. In order to better understand these choices of stitching technique and seam construction, we recreated a medieval garment based on those detailed in Poul Nørlund's Buried Norsemen at Herjolfsnes, an Archaeological and Historical Study, specifically using period stitching techniques as detailed in Medieval Garments Reconstructed: Norse Clothing Patterns, in order to understand how construction methods of these garments affected fit, shape, drape, appearance, durability, and the process of construction (Nørlund, 1924; Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 28). To better understand the differences between 14th century and modern seam and stitch techniques, we hand stitched one half of the garment as we would today and one half with the 14th century stitch choices.

First step: Patterning

We made our own pattern based on the images of garment 38 (See Figure 1) in Poul Nørlund's Buried Norsemen at Herjolfsnes (1924, p. 136) rather than using the premade patterns in Medieval Garments Reconstructed, as this allowed us to grow more familiar with the shaping of the garment before constructing it and be able to customise it to our model, Becker’s, measurements instead of a “close-enough” size.1 While this style of garment is not particularly fitted, making the garment to measure feels in line with how it may have originally been created, as we presume that the original pieces were also made to fit and not just in generic sizes.

To begin the patterning process, we measured Becker’s shoulder width with her arms raised as this circumference is the widest point of the body and affects the garment's ability to be taken on and off. This measurement came to 92.71 cm (36.5 in) and so we aimed for a final waist measurement of approximately 96.52 cm (38 in) to account for ease, small measurements of extra space added to allow for movement, a better fit. We identified the waist of the pattern pieces as the smallest point, and we electronically overlaid a grid onto the line drawings of Herjolfsnes garment 38 using Canva (See Figure 2). This grid was proportioned so that each square on the grid aligned to 1.25 cm (½ in) on the final pattern. To ensure that the waist curve was as close as we could come to the target measurements, the grid was first positioned along the waist and then expanded to cover the entire garment. This size grid allowed for precision across the differently sized pieces, kept them all in proportion to each other, and allowed them to be transferred to a full-sized pattern.

We then scaled this grid up one pattern piece at a time onto large sheets of paper to make the final pattern (See Figure 3). To test the pattern before continuing, we created a muslin test garment. As the pattern pieces did not include seam allowance, we added 1.25 cm to the edges of the garment and then sewed along the stitch lines that were marked from the edges of the pattern pieces using a machine. There were aspects of the pattern that were concerning to our modern sewing sensibilities, including the lack of closure or darts to allow room at the bust, but the muslin garment showed that the gored design provided plenty of ease and room for movement.

Trying on the test garment also allowed us to consider whether to further alter the pattern by lengthening it or to keep it in proportion with the original measurements. Becker is taller (170 cm) than the person on whom the garment was found (140 to 147 cm) and scaling the pattern up proportionally to the waist did not fully account for this height difference (Nørlund, 1924, p. 100). We considered lengthening the garment to be of similar length to what it would have been on the person it was found on, but we decided against it because we valued preserving the original proportions more than making it fall at a similar length on Becker as on its original owner.

Next step: Assembling materials

For our fabric we wanted 100% wool with a loose weave to replicate the medieval fabric. Pure wool acts in a distinct way that synthetic blended fabrics do not, and tightness of weave affects seam finishing techniques and the rate at which the fabric ravels. We used a tweed twill from Kerry Woolen Mills in Ireland, which, while slightly thicker in weave than the four shaft-twill found in most of the Herjolfsnes garments (5-6 warp threads per cm versus 8-10 per cm) it was the best approximation that we could find based on our criteria, short of weaving our own (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 88; Sanchez, 2023).

For the thread we were unable to find a 100% z twist (spun clockwise) wool thread as would have been used, so we used an undyed 100% wool lace-weight yarn instead (Fransen and Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 28). We used beeswax to wax our thread for ease of use and strength, as beeswax has been found with thread marks in it, suggesting that this technique may have been used in the period (Rogers, 1997, p. 1785).

For needles, we found that most extant examples were 50-60 mm long and 2-4 mm wide, generally either iron or copper, and not as smooth as a modern needle (Rogers, 1997, p.1785). We measured existing needles and found that antique canvas needles best mirrored the size, shape, and angular properties of medieval needles.2 Size is most important here as the size of the needle affects the size of the stitch, thread, and how big of a "hole" is made in the fabric each time the needle passes through. We used the same wool thread and pins on both sides to reduce the number of variables between the two sides, but we did change the needles. On the modern side we used a similarly sized needle, but it was smooth and round instead of angular. This allowed us to see differences created by the stitches while not using a needle we would never typically reach for on the modern side.

For the hem and sleeve cuff of the medieval side we used a tablet-weaving finishing technique (Fransen and Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 36).3 We created our own weaving tablets out of playing cards cut into roughly 5 cm squares with holes in each corner, in a manner consistent with the archaeological evidence (Collingwood, 2015, p. 26).4 We placed the holes equidistant from each other and the sides of the card, and used a hole punch to make the holes evenly sized and smooth around the edges. We worried that the thread we used elsewhere in construction would be too thin and snap too easily for tablet weaving, so we plied threads together into a 4ply yarn using a drop spindle.

Around the neckline we used a rolled hem with stab stitching, as this is detailed in both Medieval Garments Reconstructed and Nørlund's record (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.30; Nørlund, 1924, p.103). We initially intended to press the seams with a smooth stone as this is a period pressing technique; however, this was unnecessary as the medieval seams laid nicely on their own (Rogers, 1997, p.1779).

Cutting Out

In the construction of modern garments, one typically folds the fabric in half with the nice sides of the fabric facing each other and cuts out the pattern pieces once through both layers so that the two sides of the garment are mirror images of each other. With the "right" sides of the fabric folded into each other the maker is then able to trace the shape of the garment onto the "wrong" side of the fabric using chalk (See Figure 4). Before we did this, however, we smoothed the fabric with our hands to remove air bubbles and wrinkles (in modern methodology this step would have been accomplished with a steam iron). We then lay our pattern pieces on the fabric, making sure to place the pieces so that the grain, the line parallel to the warp threads of the fabric, and any nap, raised texture of the fabric that can visually alter the appearance, were all matching so as to avoid inadvertent stretch or mismatch, and making sure there would be no seams where both pieces of joined fabric were cut on the bias, the diagonal line of the fabric at a 45 degree angle to the warp and weft (Fransen and Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.39). We then marked the outlines of our pattern pieces using chalk and then also marked a 1.25 cm border around the pieces to allow seam allowance, except for the bottom edge where we left a 2.54 cm (1 in) hem allowance. While we do not have proof that the medieval dress was originally marked with chalk or that it used precisely a 1.25 cm seam allowance, the types of seams they used (and that we use now) require seam allowance and 1.25 cm is standard. Marking the pattern pieces on the fabric also allowed the pattern to be checked visually (such as ensuring similar lengths) which is important, especially given how valuable fabric was. Although we cannot be sure about the use of chalk on this specific garment or even in a domestic garment creation setting, there is evidence that chalk was used by tailors in the 14th century in the process of garment making (Scott, 2007, p.114).

As we cut out the pieces, we also marked them with the number we had chosen for each pattern piece on the wrong sides of both the medieval and the modern pieces. This denotes both which pattern piece is which, as they are all similarly shaped, and the wrong and right sides, as the fabric is not notably different on either side. While some fabrics have a difference in colour or weaving pattern on the back due to their production, this twill-woven fabric does not.

Singling

Our next step was to sew the singling on the edges of the fabric pieces for the medieval side of the dress. Singling is a technique wherein one sews a "wavy" line of stitches along the edge of a piece of fabric to attempt to secure the individual threads together to keep the fabric from unravelling over time (See Figure 5). This technique was found specifically on the hem of Herjolfsnes garment 38; however, we used it as stabilization for all internal seams in the dress as suggested in Medieval Garments Reconstructed (Fransen and Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.29-30). While we cannot conclusively determine what (if any) seam finishings were used on the internal edges, due to the loose weave of this fabric, some sort of seam finish technique is vital to it not unravelling during construction and wear (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.32). The singling also served to stabilize the edges that were cut on the bias (cross grain of the fabric), as these edges tend to stretch and warp out of shape.

We made a sample of the singling to test its effectiveness. We cut out a rectangle of fabric and singled one of the long sides, left the opposite long side untouched, and then used a serger to finish one of the short sides as a comparison. The rectangle was 10.16 cm (4 in) wide with a line down the centre so that we could measure the amount that the fabric frayed (See Figure 6). We then put this sample into a modern washer on a regular cycle (cold water / no soap) to rough it up. This is not representative of how the seams of the garment would necessarily fray, as the seams of the garment would have been protected by overcasting and underlayers, and been hand washed, but this allowed us to quickly cause the edges of the fabric to fray. Both the singled and untouched sides frayed, but the singled side frayed less and held together noticeably better (See Figure 7). The furthest edges of the fabric on both sides remained approximately 5 cm (2 in) from the centre line, but the untouched side frayed out about 1 cm before there was any integrity to the fabric and the singled side frayed out about 0.6 cm at most. The machine overlocked edge did not fray out at all. This indicates that the singling, as expected, does a good job of preserving the fabric and preventing it from fraying as there was less fraying and it was a cleaner, more manageable fray.

We found sewing the singling onto the garment to be an intuitive and simple process. We eyeballed the seam allowance instead of measuring precisely, as it is more efficient and just as practical since the singling gets incorporated flat into the fabric. We stitched from the wrong side, that is with the wrong side up, as that is the side with larger and more visible stitches. This effectively secured the individual threads to each other and made it difficult for the fabric to fray out in large quantities. In some ways this was like pre-emptive darning as we sewed the weave of the fabric together so that it held to itself.

Period Seams

The period seams were sewn according to those described in Medieval Garments Reconstructed. This first involved lapping the fabric: the seam allowance of the top layer was folded to the wrong side of the fabric and this fold was then aligned with the edge of the seam allowance on the bottom layer. This resulted in the two layers overlapping with the seam allowances together. They were then sewn along the underside of the lapped portion from the outside so that the stitch went through both layers of fabric but was not visible from the outside of the garment (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 28). This is not a standard modern technique and took some getting used to. It is like how the seams on the inseam of modern jeans are sewn, however jeans are sewn with visible top stitching while the medieval seams are not visible from the outside. The medieval seam is also barely visible on the inside as the stitches are so small that they disappear in the weave, like a running stitch, but less visible. This technique makes it so that both seam allowances are already together and to one side which makes it easy to overcast without pressing (See Figure 8). The overcast seams were not bulky and tended to drape nicely (See Figure 9).

Modern Seams

For the modern seams we used a backstitch, a standard modern technique for hand-sewn long seams that involves stitching back halfway through the previous stitch to “knot” the thread together to make a sturdier seam. Originally, we planned to use a running backstitch, where there are several running stitches, taken with a backstitch interspersed every couple inches. The weave on the fabric was thick enough that the running back stitch gaped. The use of wool thread did not affect this technique beyond it occasionally snapping - the thread is a relatively loose twist, and it snapped more often than typical modern thread, even when waxed. Once we backstitched the seam, we folded the seam allowance down and used a whipstitch, a stitch that involves stitching around the edge of the fold/raw edge of the fabric to hold it flat and to secure the fabric to finish the edges. The end result was bulkier than the medieval seam and did not lay flat nicely without ironing (See Figure 10).

Insertion of Gussets

Both the front and the back of the garment have gussets at their centre. A gusset is a piece of fabric (often triangular) sewn into a seam to give a garment more volume and was common in medieval European garments. Gussets give volume to an otherwise rectangular garment, which is advantageous for fabric-saving purposes, and allow one to cut a garment out of relatively standard geometric shapes. Gussets are often a tricky part of the sewing process as they require adding three-dimensional volume to two-dimensional fabric. To insert gussets in our garment, we cut a slit up the front and back of the fabric to the length of our gussets. An advantage of working with a loose-weave twill is that the individual threads are very easy to follow when cutting. This gave us a straight line directly in the centre of the front and the back. Originally, we had planned to do one half of each gusset in each seam technique, but we discovered that this does not work due to the difference in the seams and decided that we would have a more accurate representation of the process and finished product of each gusset if each was done with only one technique. Accordingly, we used a back stitch to attach the back gusset (See Figure 11) and a period stitch for the front gusset (See Figure 12).

To our surprise we found that the period stitch made the insertion of the gusset much easier. The ability to work from the outside made it easier to ease the fabric together, especially around the point of the gusset. The finished product laid flat and did not pull or bunch the fabric like the backstitch did. A modern equivalent of this may have been to topstitch the gusset, which would make gusset insertion easier as it allows you to work from the outside. However, top stitching along the top point while keeping the top fabric folded so that you do not have any exposed raw edges can be difficult because the fabric tends to slip where the seam allowance is smaller. The medieval technique helps this issue as it allows you to work on the fold, making sure that you keep it folded over and the raw edge enclosed. Given the prevalence of gussets in pre-modern clothing it makes sense that sewing techniques may have been geared towards their insertion. The finished front gusset looked much smoother than the back stitched gusset. While the back stitched gusset could probably be remedied with some pressing, since medieval people did not use steam irons for pressing, but only slick stones, it makes sense that they would have used a technique that minimized the need for pressing.

Comparison of stitching techniques

In general, the medieval stitching technique was simple to pick up, made the gussets much easier, and allowed the garment to drape better without ironing when compared to the modern stitching technique. The time and thread usage of all the stitches that we used can be seen in Table 1. There is some variation in these numbers as we are hand stitching and are not as consistent as a machine, but they are a solid representation of how much material is used on average for each stitch.

| Stitch | Time for 1 foot of stitching (minutes) | Thread usage for 30 cm of stitching (cm) |

| Singling | 4.75 | 36.2 |

| Modern Backstitch | 4.5 | 60 |

| Medieval Stitch | 4.5 | 42 |

| Overcasting | 5 | 62.2 |

| Modern Catch Stitch (Hem) | 2.75 | 50.8 |

| Tablet Weaving (Hem) | 60 | over 450 |

Table 1. The time and thread usage of all the stitches that were used.

Though there is not a direct relationship between the amount of thread used and the strength of the resulting stitch, the backstitch is tighter. This can be best demonstrated through pulling the two pieces of joined fabric away from each other while looking at the seam where they are joined (See Figures 13-14). This exposes the stitches, and looser stitches will show more when the same tension is applied. The modern stitches do appear to be tighter, but such strong stitches may not be needed for those seams which do not bear the weight of the fabric when worn or are not in areas where significant force or tension is applied.

The drape of the dress with the seams can be seen in Figures 8-11. Neither the period or the modern side have been ironed, and the modern stitches are visibly stiffer and do not allow the fabric to drape as gently as the medieval stitches. They also pull more, causing ripples in the fabric, due to increased tension on the fabric from the tightness of the stitches. This can best be seen at the gusset centre back.

Modern Hem

The modern hem was done by turning the bottom edge up 1.25 cm and then turning that up 1.25 cm again so that there are no exposed raw fabric edges at the bottom of the garment. This was then secured with a catch stitch (See Figure 15). This technique secures the raw edge of the fabric inside of a rolled hem by sewing back and forth between the hem and the dress, "catching" an individual thread of the dress to make a very small stitch that is not visible when the dress is worn. The rolled-over fabric resulted in a highly bulky hem, especially as it was not ironed in place, but it is a quick method that does not use a huge amount of thread.

Importantly, this type of hem increases the fabric needed as it requires an extra inch of fabric on the bottom of every piece. This means that when the bottom edge of the garment wears out, the most effective method of repair is to remove the stitches from the hem, cut off the fabric above the damage, and turn up the hem again. This would then shorten the garment by the amount turned up in the hem, in this case 2.54 cm. Which means that once the inevitable wear and tear happens to the bottom edge, the repair process would significantly shorten the garment.5

Tablet Weaving

Enclosing the raw edges in tablet weaving was the technique which took the most time to learn.6 Though we had done a few practice samples previously to make sure we had an idea of what we were doing, it took a while to get the hang of managing it on a full garment. Once we had made the cards (See Figure 16), we needed to set up our "mini loom". Based on extant images, as well as Peter Collingwood's ethnographic research, the warp is tied off on either end, either to a sturdy object or a person (Collingwood, 2015, p. 26). The Virgin Mary is often depicted engaging in wool work in the medieval period, and a French book of hours from the fifteenth century shows her manipulating the cards as she tablet-weaves thread which she has suspended between two poles (See Figure 17). This image helped us get a sense of how to set up our "mini loom." For our purposes, we tied one end off to a set of shelves, and the other end to a chair that could be moved backwards to create tension on the warp. Fransen et al. describes the warp as three-strand, which we took to mean three individual cards (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p. 32). In each card we passed about twice the length of the hem through each of two diagonal holes. We then repeated this process on two more cards. In total this left us with six warp threads, which is consistent with the six-thread twist that is described on a variety of the garments that were found with the dress we are recreating (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.36). From here we slip knotted all the threads together on either side of the warp and passed a braided length of yarn through these knots which was then secured to the shelves and chair (See Figure 18). This left us with our warp.

For the weft, we started with a length of thread with one end through a needle. We first did several passes of just weaving into the warp of the tablet weaving by passing the weft through the warp, spinning the cards 180 degrees, then passing the weft back through the warp. We did this to create some tablet woven cord before we introduced the garment to secure it in the finishing process. We also removed the extra 2.54 cm added to the hem when it was cut out as that fabric was for the modern hem and was superfluous for this hemming technique. We found the tablet weaving to be difficult, especially beginning the process. One of the first issues that we ran into was the fabric unravelling as we attempted to do the tablet weaving. Singling around the bottom edge of the medieval side of the garment helped with this issue. However, we were still struggling to begin the tablet weaving on the fabric, so we added reinforcement threads as depicted in Medieval Garments Reconstructed (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.32). These threads were sandwiched between the weft threads on the backside of the fabric and the hem itself to keep the weft from ripping through the fabric, however they were not woven in like the warp (See Figure 19). Once we got the weaving started, the process became easier over time, though juggling the reinforcement threads, the warp, the weft, and the cards took getting used to. Using the needle to weave through the warp and into the fabric meant that there was a large quantity of thread to pull through on each pass, especially at the start. This process was the most time-consuming of any steps but was also the step in which we had the least prior experience. Lining the weaving up so that the bottom edge of the fabric was encased within the weaving was challenging, and in some cases the warp threads of the fabric were still visible below the weaving (See Figure 20). While this would not affect the longevity of the fabric as it was secured just above the thread, it did affect the appearance, and so we worked to minimize it. This method left the tail ends of the warp of the tablet weaving at the beginning and end of the sections loose. We chose to secure and finish these edges by tucking the tails underneath the seam allowance of the seams joining these edges.

Sleeves

The sleeves were challenging, as they are shaped differently than any sleeves we had previously worked with. In a modern pattern, or more recent historical ones, the sleeve is typically either gently gathered at the top to create shaping that mirrors the shoulder itself and allows for movement or will have a gusset that goes at the underarm seam to create room in the bottom part of the armscye. However, our pattern had a gusset that appeared to have been made to go on the sleeve and not the body of the garment and was positioned at the back of the arm. Medieval Garments Reconstructed is unclear about how to place the sleeve and how precisely it worked, so we pinned a mock-up of the sleeve on the body of the garment as best as we could to figure out where the gusset went.

When we made this initial mock-up of the sleeve, we found that it was too big for the armscye. This could have come from the drawings that we scaled up not being perfectly in proportion to each other or an error in the pattern transfer. We had to take out about 3.8 cm (1 ½ in) so we took 0.64 cm (¼ in) off of the top portion of each side of the gusset and 1.9 cm (¾ in) off of each side of the sleeve and 1.25 (½ in) cm out through a slit cut straight through the sleeve from the cap to cuff, the edges of which are then overlapped in a tapered fashion to remove 1.25 cm at the cap of the sleeve and none from the cuff. This followed standard modern practice for altering patterns and allowed us to maintain the shape of the sleeve and the curves and angles that were reflected from the initial pattern while removing the necessary volume.

Trying on the mock-up showed that this sleeve placement resulted in the extra volume of the sleeve being where movement occurs and needs accounting for, namely with the shoulder blade. This also resulted in movement not being limited by large armscyes as it is in many modern garments where the whole garment must move with the arm. The shoulder seam was placed further back than many modern garments, which typically have it fall at the top of the shoulder, but the “standard” placement of shoulder seams has moved throughout history. This seam placement does mean that the cap, or top of the sleeve, was not lined up with the shoulder seam, as that made the sleeve and fabric pull. Instead, the top of the shoulder on the sleeve and the top of the shoulder of the garment were aligned. This resulted in the low point of the curve of the sleeve sitting further forward on the armscye than initially expected. Positioning the gusset at the underarm would only push this low point further towards the front of the garment and so it did not seem to be an indication that we placed the gusset too far back.

As we worked on the sleeve, we consulted Mary Ann Kelling, Lecturer in Costume Design and Construction at Carleton College. She suggested that we think of the sleeve gusset less as a gusset in a modern sense, and more as an extension of the sleeve to give the wearer more space. She agreed with our placement of the sleeve based on the shape and placement of the sleeve cap, and posited that the fabric from which the sleeve was cut was relatively narrow, and therefore a wider sleeve was not possible without this kind of "sleeve extender" (Kelling, 2024). This idea is supported by the sleeve being the widest pattern piece of this garment and of the other garments depicted in Buried Norsemen at Herjolfsnes, and thus potentially indicates the width of the loom or uncut fabric (Nørlund, 1924).

We also contacted the Danish National Museum to see if we could access pictures from additional angles to better understand the sleeve design (Laursen, 2024). Based on their photos, the gusset seems to have been somewhat lower in the armscye than we had originally thought, but still not directly under the arm as it would be in a modern garment (National Museum of Denmark, 2024). While the possibility exists that the sleeve fell off in shipping and was reattached in the 1920s in a contemporary style, as this is noted to have happened to some garments (Nørlund, 1924, p. 39), images of other garments from the same site do show that the gusset tended to be in the lower back of the armscye.

We constructed each sleeve with the same style of techniques as the corresponding side of the garment. For the medieval sleeve this involved singling around the edges of the sleeve piece, stitching the gusset to one side of the sleeve, overcasting that seam, and then top stitching next to the seam using a running stitch (See Figure 21). This last technique was used in the original garment, and we suspect that it was to reinforce the seam as this area gets high amounts of stress due to arm movement (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.32). We formed the other seam by attaching the unattached side of the gusset to the corresponding side of the sleeve and then continuing this seam to the cuff so that it attached the two opposite sides of the sleeves together. Before doing this last seam, we tablet weaved the hem of the cuff as it is far easier to do this while the fabric is still flat as opposed to in its final shape of a tube.

We constructed the modern side similarly, but by using the modern backstitch instead. This means, like with the back gusset, that we were working from the back of the seam. We found this gusset to be easier to insert than the back gusset since this gusset ended with a seam instead of a slit in the fabric. This means there was seam allowance that could be manipulated at the smallest point of the gusset instead of it tapering into nothing. The steps were the same as the medieval seams only without the topstitching around the gusset. We then hemmed the cuff in the same manner as the bottom of the garment (turning up 1.25 cm and then 1.25 cm again to conceal all raw edges) before we did the final seam of the sleeve. To ensure all raw edges were concealed on the final cuff the hemming was left unfinished immediately on either side of the seam so that it could be finished after the seam was completed. We left the seam allowance unhemmed until the seam was completed and then finished the hem so that no raw edges remained at the bottom edge of the sleeve. This hem was just as bulky as the bottom of the garment, and perhaps more bothersome because it lies directly next to one’s hand.

The medieval sleeve was incredibly difficult to pin, and we ended up pinning it on a mannequin. There is ease in the sleeve as it goes into the armscye, and this is simpler to manage when pinning right sides together as we do on the modern sleeve. Once it was pinned, the sleeve was straightforward to stitch and work the ease in on, just as with the modern construction methods. The sleeve is the one place where the Medieval method seems to be a hindrance, but that could be due to our inexperience with this method of stitching.

On the modern side we then used a backstitch from the inside to attach the sleeve to the body of the garment with a 1.25 cm seam allowance. We then overcast towards the sleeve so that it went with the direction of movement when the garment was put on. This is a relatively common modern technique. The cuffs of the sleeves on the original dress might have been slashed open at the seams of the sleeves, perhaps to help with greater ease of movement (Nørlund, 1924, p.100), and images from the National Museum of Denmark (2024) leave unclear if they were sewn up after excavation. We chose to sew them closed, but they could easily be opened, and the seam allowances could be finished either with tablet weaving or in the same manner as the neckline and could also be fastened together, as many modern dress sleeves still are.

Pockets

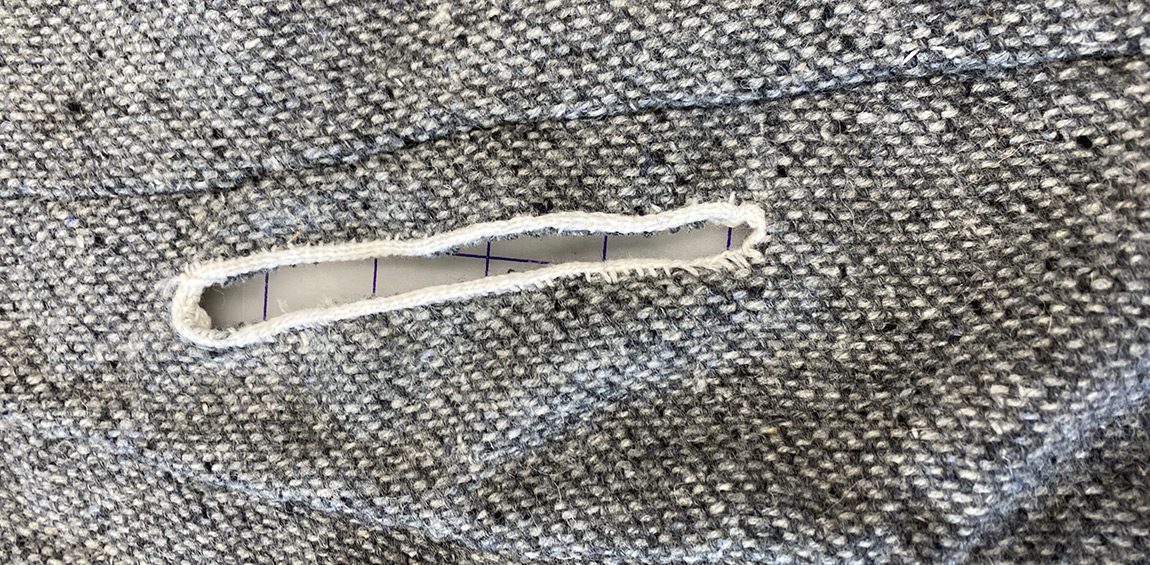

The pockets on this garment are different from modern pockets as they did not involve attaching either bags to the openings, such as on the front of modern jeans, or adding fabric to the outside to make “patch pockets,” such as on the back of modern jeans. Instead, the “pockets” on this garment are protected and reinforced slits in the fabric that give access to small bags worn underneath and tied around the waist.

For the pocket on the modern side, we cut the slit in the fabric as marked on the pattern. We then turned both sides back to the inside of the garment about 0.64 cm. We tapered this down to nothing on either end of the pocket slit to avoid awkward pulling and having to cut into the fabric more than necessary. The turned back fabric was then stitched down using the same overcast stitch that was used to finish the seams. Since this left the ends of the pocket slits as raw edges, we used a buttonhole stitch to cover and protect that part of the fabric (See Figure 22).

This method resulted in a bulky pocket that gaps open because we removed about 1.25 cm of fabric from the garment. Ironing it may have improved its aesthetic shortcomings. We are unsure about the longevity of this method of finishing the pocket because the fabric is only turned back once and secured with a hand overcast (See Figure 23), and this part of the garment would get significant wear from moving your hand and objects in and out of the pocket. Thus, the edges of the fabric could still fray especially with heavy use.7

We cut open the medieval pocket in the same manner but then used tablet weaving to finish the edges (See Figure 24). This, as with the hems of the garment and the sleeve, reduced bulk and did not gape, but was more time intensive. We found it difficult to try to turn a corner while tablet weaving continuously so we tablet weaved each side of the pocket individually. We then stitched the ends of the tablet, weaving down inside the pocket on either end to secure and finish those edges and the corners (See Figure 25).

The medieval method of finishing the pockets removed the issue of creating or enlarging a hole in the garment, made the finishing work on the pocket more aesthetically pleasing and consistent than the modern method, and left all the raw cut edges of the fabric protected. Overall, the medieval method seems simpler, as it uses only one technique that is used elsewhere on the garment, while the modern method required multiple stitches and techniques.

Neckline

We worked the entire neckline according to the example from Medieval Garments Reconstructed (Fransen, Nørgaard and Østergård, 2011, p.30). We did not sew a modern neckline over half of it because it would have involved doubling the fabric over twice and stitching it down, and this fabric was too thick for this technique. Instead, we folded the entire neckline down 1.25 cm and sewed two seams of stab stitching through all the layers around the neckline then overcast the raw edge to the inside of the neckline (See Figure 25). This made for a very flat neckline. While it might have been prone to ravelling due to the raw edge being only enclosed by overcasting, it looked quite nice from the outside.

Conclusions

The medieval stitches made sense to make a sturdy and attractive garment with the kind of fabric available at the time in which they were made. The medieval seaming technique made for seams that laid flat and were not bulky, while the modern backstitch made for bulky, heavy seams that made the fabric bulge, especially on the side gores (See Figure 26). The modern seam may be improved by ironing, but we did not want to introduce a steam iron as they were not available in the medieval period. The medieval stitch worked quite well on a thicker weave fabric as it was easy to isolate individual threads to stitch through on the top and the bottom, making for a stitch that was not visible from the outside and barely visible from the inside. This seam was potentially developed for a thicker weave fabric and fell out of fashion as fabrics became more finely woven since it would be harder to isolate threads in a finer fabric. The modern backstitch, on the other hand, was very visible on the inside and created a bulkier seam on the outside. While we initially thought that the medieval stitch was not as sturdy, once the inside seams were overcast down to one side, it felt very sturdy as there was no longer the same amount of tension being put on the seam.

The medieval stitch also made the gussets much easier to set in as it allowed us to work from the outside and manipulate the fabric around the point of the gusset quite smoothly (See Figure 27). Gussets are notoriously tricky when worked from the inside. The medieval technique makes sense as gussets were a very common way of adding volume to otherwise primarily rectangular medieval garments, such as a tunic. This not only allowed for added movement and appeal of appearance but was also a fabric-conserving measure as it allowed one to use geometric pieces with straight edges which generally use, and waste, less fabric. Many, if not all, of the garments found at Herjolfsnes have at least one gusset in them, and gussets continued well into the early modern period as a standard way to add volume into basic garments. Aside from fabric conservation, the medieval stitch also used less thread when compared to the backstitch. This makes sense intuitively; the stitch runs forward rather than doubling back on itself. However, it provides another reason why this stitch may have been popular given the sheer amount of effort, time, and materials used to make sewing threads.

One place that did not conserve thread, however, was the tablet weaving step. It required eight threads that were double the length of whatever area we were trying to tablet weave and then another length of thread for the weft. Additionally, there was a bit of waste as there needed to be excess on either side of the garment to tie off. However, the tablet weaving provided a very pretty edge, did not add extra bulk, and would have been easy to replace if it wore out as you could just trim it off and add a new line of tablet weaving around the exposed edge. On an aesthetic level, it also provided space for decoration and possibly the addition of colour or design in the garment. The tablet weaving was, additionally, the most time consuming of the steps. However, this could be because this was the part of the project with which we had the least experience. With thicker thread and more experience, we may have been able to do this at a faster rate. Nonetheless, it may have been a worthwhile time investment as it looked aesthetically pleasing and extended the longevity of the garment.

One of the most challenging aspects of this garment was setting in the sleeves. Once we had some idea of how they went into the garment, we found that the medieval stitch made it difficult to attach them (See Figure 28). We are not used to attaching sleeves from the outside, and having to turn the seam allowance under made it difficult to work with easing the sleeve into the armscye. Given that this seaming technique was most effective on gussets, it is possible that it was developed for the insertion of gussets and similar seams and then just used as standard throughout the garment.

Final Thoughts

We set out on this project to figure out "why did these stitches exist" and, to some extent, we found our answer. In a world before sewing machines, where garment construction was done by hand and wool was a valuable resource, these stitches make sense. Sewing from the outside of the garment uses less thread and allows for more control over the shaping of the fabric and stitching. This allows for minute changes on the go which lead to a cohesive garment and decreases the need for pressing your seams after the fact. In fact, once we had the dress finished and it was on a mannequin in the costume shop, several of our costume construction colleagues remarked that the medieval side looked more professional and "modern" than the side that used the modern sewing techniques.

We hope that this recreation not only helped to figure out our question about the stitches but also speaks to the importance and versatility of garments which are not only well-made, but also repairable, a problem for our own time. Finally, we hope that our project helps to illuminate the beauty and design of these garments which have spent a good 700 hundred years in a bog.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Carleton College Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Archaeology, and Classics departments for helping fund this project, as well as Bill North, Mary Ann Kelling, and Alejandra Sanchez for their advice, support, and generous sharing of knowledge.

- 1

We needed to size up the dress as the original is quite small, with waist measurement 94 cm and neck-opening 76 cm. (Nørlund, 1924, p. 95).

- 2

We hope to forge our own needles for future historical reconstruction projects.

- 3

See also the discussion of “false cording” (Nørlund, 1924, p. 101).

- 4

Extant pieces of Medieval weaving tablets were made of wood, bone, or vellum (Collingwood, 2015, p. 25).

- 5

There is later evidence of trim being used to extend the longevity of garments with turned up hems as the trim would take the damage and could be removed and replaced without having to cut off part of the garment itself and shorten it, but that is not a common modern technique (Banner, 1898, pp. 144 and 148).

- 6

For more detailed information and thoughts on tablet weaving see Palmer's June 2024 EXARC publication on tablet weaving “Tarquinia’s Tablets: a Reconstruction of Tablet-Weaving Patterns found in the Tomb of the Triclinium.”

- 7

We considered using bias tape to bind the edges of the pockets, but modern bias tape is made out of cotton and/or polyester and we did not want to introduce these extra materials and variables to our project. The dress fabric was not fit for making bias tape as it was too thick and too loosely woven.

Keywords

Country

- Greenland

Bibliography

Banner, B., 1898. Household Sewing with Home Dressmaking. London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

Collingwood, P., 2015. The Techniques of Tablet Weaving, illustrated ed. Brattleboro, Vermont: Echo Point Books and Media.

National Museum of Denmark, 2024. D10580. Available at: < https://samlinger.natmus.dk/assetbrowse?keyword=D10580 > [Accessed 19 January 2024].

Fransen, L., Nørgaard, A., and Østergård, E., 2011. Medieval Garments Reconstructed: Norse Clothing Patterns. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press.

Kelling, M. A., 2024. Conversation with Helen Banta and Ruby Becker, 18 January.

Laursen, M., 2024. Email to Ruby Becker, 19 January.

Nørlund, P., 1924. Buried Norsemen at Herjolfsnes, an Archaeological and Historical Study. Copenhagen, Denmark: C.A. Reitzel Boghandel.

Palmer, R., 2024. Tarquinia's Tablets: a Reconstruction of Tablet-Weaving Patterns found in the Tomb of the Triclinium. EXARC Journal 2024/2. https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10745.

Roesdahl, E. and Verhaeghe, F., 2011. Material Culture -- Artifacts and Daily Life, in M. Carver and J. Klápště, eds. The Archaeology of Medieval Europe Vol. 2: Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, pp.189-227.

Rogers, P. W., 1997. Textile Production at 16-22 Coppergate, in P.V. Addyman, ed. The Archaeology of York: The Small Finds 17. Walmgate, York: Council for British Archaeology.

Sanchez, A., 2023. Conversation with Ruby Becker, 3 November.

Scott, M., 2007. Medieval Dress & Fashion. London: The British Library.

Sources for images

Fig 1. Image of Woman Wearing Herjolfsnes Garment. From The National. Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark, ca. 1954. D10580. Ikigaat., Grønland. https://samlinger.natmus.dk/dmr/asset/213050.

Fig 17. The Virgin Tablet Weaving. Book of Hours. Use of Paris. Paris, France ca. 1407. 19r. Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Douce 144. https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/342f4ed5-d93c-4d1b-bf7e-310c2…