The historiography concerning the Garum, as well as the archaeological evidence of the same, are very wide and cover the entire topic both from the historical and archaeological points of view. Can a team of archaeologists faithfully recreate Garum today, starting only with the historical knowledge available to us, and at the same time being careful to use the methods and materials that the ancient Romans had at their disposal to make this product?

Garum And Its Sources

By Piga Tania

The word “Garum” is usually used for one of the most famous sauce in Roman cuisine which is amply documented in ancient sources. Some Latin authors of the 1st century AD give us important details and anecdotes about this condiment. Pliny the Elder in the book 31 of Naturalis Historia reported that, except for perfumes, there was not a liquid substance more expensive than garum, thus underlining the prestige of this sauce so loved by the palates of Romans and others, as shown by a quote from Pliny the Elder (31.43, (par._94)):

“Nec liquor ullus paene praeter unguenta maiore in pretio esse coepit”.

“Nor any other liquid, except perfumes, began to cost more”

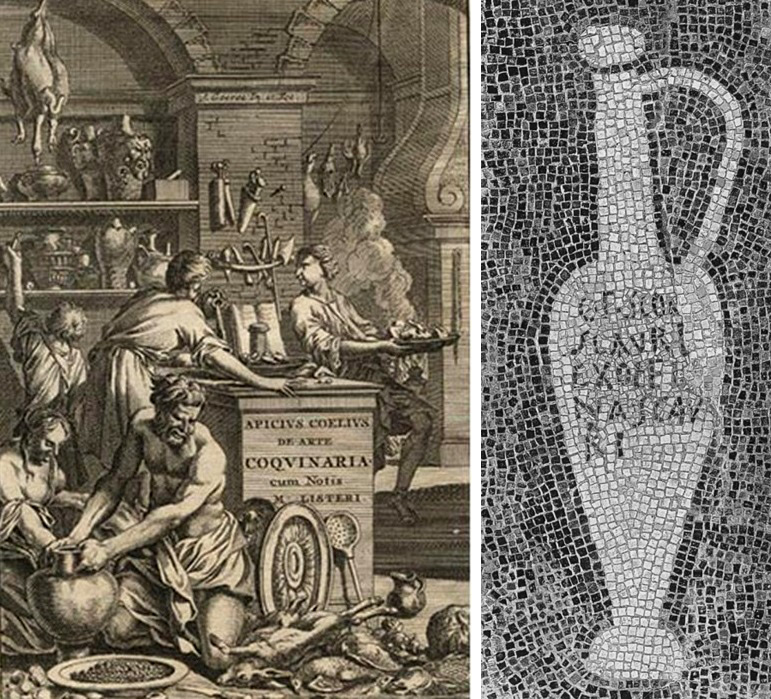

Garum was not only used as a sauce for dishes, but also in medicine: it was used to treat ulcers, and diseases related to the inner ear canal. Pedanius Dioscorides, Greek doctor and botanist of the 1st century AD, during Nero’s reign, recommended the use of garum for many ailments, as an ointment to cure sores, for dog bite problems, and even administered orally as a remedy for dysentery and sciatica (De Materia Medica, 2.32). The picturesque description that Petronius of the 1st century AD, provides us with, in his main work, the Satyricon, is interesting: in the “Cena Trimalchionis”, we find garum, which was poured over fish from small wineskins (36). In contrast, two other authors of the same century, Seneca and Martial, do not seem to like the famous sauce. The former reported his aversion to garum in a letter to Lucilius, governor of Sicily at that time (Seneca, Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, 95.25). Martial, on the other hand, emphasised the pestilential smell of this sauce by ironically comparing it to the breath of a certain Papilo, famous for being somewhat lacking in personal hygiene (Martial, Epigrammata 7.94). Apicius was a famous Roman gastronome, and contemporary of Tiberius. An important cookbook is attributed to him, “De re coquinaria”, of which we have a reconstruction in Vulgar Latin dated to 3rd or 4th century AD. In his work, Apicius focussed on the importance of seasoning; in Book 10, fish sauce was the condiment of particular interest. He suggested using garum or better liquamen, as he called it, to season a wide variety of foods from meat and fish to vegetables and fruit.

An important Christian writer, Isidore of Seville, in Book 10 of his work Etymologiae sive Origines, dedicated to the home and domestic instruments, wrote:

“Garum est liquor piscium salsus, qui olim conficiebatur ex pisce quem Graeci GARON vocabant; et quamvis nunc ex infinito genere piscium fiat, nomen tamen pristinum retinet a quo initium sumpsit. Liquamen dictum eo quod soluti in salsamento pisciculi eundem humorem liquant”.

“The sauce garum is a liquid made from fish, which formerly was made from fish that the Greeks called GARON, and although it is now made from any kind of fish it retains the original name that it had at its beginning. Liquamen is so called because little fish dissolved in pickling brine liquefy (liquare) as that sauce” (20.3.19-20).

This sauce was made using different types of fish based on which the quality and price could then be determined. It is possible that before Romans, the Greeks were the first to prepare this sauce using a type of fish called γάρον. From the name of this fish, whose shape and appearance are unknown, this condiment so dear to the Romans would take his name. Garum sauce was obtained by fermenting certain types of fish, or parts of them, in brine. Just as the ancient Greeks preferred this now-unidentified fish, the Romans preferred to prepare the sauce using mackerel, which was fished in the Western Mediterranean, especially along the coastline of Mauretania and Hispania (Mauretania was the Roman province roughly corresponding to Morocco; Hispania was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula) (Pliny the Elder, Nat. His.,31.43 (par. 94)). We know very well the great variety of the aquatic fauna of what the ancient Roma. ns called Mare Nostrum.

The method of garum preparation is a mystery: the available sources are inconsistent and there is sometimes confusion around similar condiments such as liquamen and muria. Liquamen, as the name suggests, was not a sauce but a liquid product. Probably, since the end of the second century AD. garum and liquamen became synonyms. It is even assumed that Liquamen had taken over from when the Greek word γάρον was translated into Latin as liquamen and not garum within the Edict of Diocletian (Edictum De Pretiis Rerum Venalium, 301 AD). In addition, the combination of garum with other substances could give rise to variations

- Oneaogarum= Garum + Wine;

- Eleogarum= Garum + Oil;

- Oxygarum= Garum + Vinegar;

- Hydrogarum= Amalgam of Garum with water.

The basic ingredients for the garum base recipe are fish and salt. Obviously, the recipe does not cover all types of fish: it needs only some specific parts of the fish. Garum may also have another characteristic: it can be cooked or raw.

the first group involve cooked fish:

- Garum prepared with offal and waste;

- Garum prepared with small entire fish;

- Garum prepared with both.

The second used raw fish:

- With prior maceration;

- Without maceration.

The cooked production is unambiguous in ancient sources (Pliny the Elder, Pseudo Rufius Festus, Isidore of Seville). According to the sources the vessel has to be new and made of a copper alloy or iron (Pseudo Rufio Festo; Geoponica). Once the product has been removed from the heat it is filtered for clarity. According to the sources, this step can take place either hot (Pseudo Rufio Festo) or cold (Geoponica). Once this step is completed, garum is placed in a well- sealed vessel, or alternatively simply kept covered or stored in a glass cruet.

Type of Production Plant for Fish Sauces

By Gorga Alessio

The morphology and size of fish sauce production plants are highly variable, although they can be classified according to the shape and relationship of the basins with the corridor or central room. As for the total size of the plants there is no single standard, with small centres, less than 50 m2, and others sizeable with more than 1000 m2. Although cetariae, as the sauce production centres were called in Latin, have a certain regional and chronological variability, three main types can be identified:

- Installations with basins on two or three sides around the centre, forming a U or L (within this type, some plants have a layout developed not around a single central space, but around two).

- Centres which have a series of rooms arranged immediately after access by means of the back bound tubs

- Centres providing for a central corridor along which parallel rows of basins are arranged

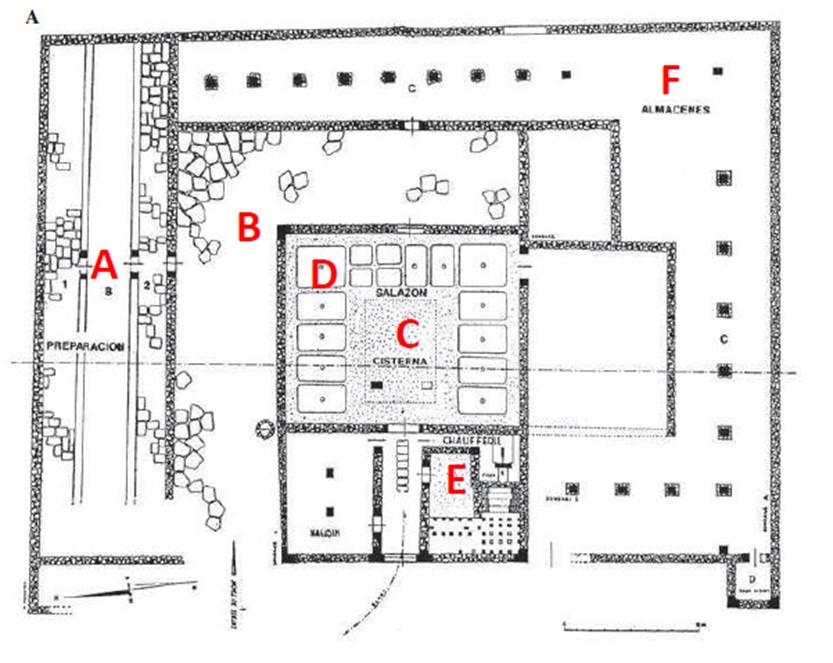

The Tangi Cotta plant, a Roman town in the province of Mauritania Tangitania (corresponding to the western part of Morocco), is the best example of the first type and is useful for understanding the processing methods. It is a rectangular building with a tower at the entrance, a Thynnoskopeion, intended for the sighting of shoals of tuna, defence and as a guide for navigation (lighthouse) (Bernal Casasola and Garcia Vargas, 2014, pp.301-302). On the northern side there was a long nave (See Figure 1 A) equipped, in the central part, with a series of low parallel walls designed to support benches for processing and cleaning the fish. In the courtyard (See Figure 1 B) L-shaped which separated the nave from the central building there was a well, a precious source of fresh water necessary for the various Operations. The inner part of the cetaria (a centre of garum production) was formed by a rectangular building with a central space (See Figure 1 C) equipped with complivium (a square opening in the roof) for the collection of rainwater, around which are arranged the characteristic basins dug underground and covered in opus signinum to make them waterproof (See Figure 1 D). Usually these reservoirs, with a capacity ranging from 1 to 15 m3, are quadrangular or rectangular in shape but in some cases, such as Baelo Claudia, an important archaeological site in Andalucia (Spain), some tanks are circular. In Cotta is also present inside the central building a room with hypocaust (See Figure 1 E) with unspecified functionality, probably used for the production of small quantities of salt, or to speed up the process of preparing fish sauces by means of heating.

The cleaning rooms on the east and south sides (See Figure 1 F) are large, with large pillars to support the roof and are large stores for storing fish, salt and amphorae. Plants of this type had a considerable production volume, for Cotta it is assumed 258 m3 of salt and fish sauces while for some centres present in Tróia (Portugal) a volume of as much as 300 m3 is assumed.

In the second category of plants the tanks containing fish sauces are instead located in the back of the building and are usually arranged on parallel rows (as in Baelo Claudia).

The third type has two rows of basins lined around a central corridor. In almost all cases, these are small urban production centres, like in Huelva (Spain) (Campos Carrasco, 2011, pp.55-91) although some are found in rural locations, as Olhão in Portugal (Silva, Soares and Coelho-Soares, 1992, pp.335-374). A variation of this type is the one that has two wings around the axial corridor, in one of which there are the reservoirs while in the other there are rooms dedicated to different functions (Complex V of Baelo Claudia) (Garcia Vargas and Bernal Casasola, 2009, pp.156-157).

A second typology, proposed by J. Edmondson (1987, pp.102-124; 1990, pp.123-147), distinguishes the production centres according to the context in which they are built:

- Rural installations: small installations connected to the village and where staff are employed both in the fields and in fisheries. The production of these centres served mainly to meet local needs, hence for self-sustaining or regional distribution.

- Urban installations: centres where production was carried out intensively. Two aspects considered particularly positive for these types of ateliers are the ease of finding labour and the possibility of selling products within the city. In addition, the frequent presence of a port in the city facilitated the marketing of products to the outside world.

- semi-urban plants: integrated within vici usually having mainly productive function. This third type is considered by Edmondson to be the most profitable and cost-effective because it allowed a better organization of work (Botte, 2009, p.101).

In any case, the construction of salting products and fish sauces centres is quite functional, with rare artistic decoration (Garcia Vargas and Bernal Casasola, 2009, pp.133-156). The building materials are usually local with the frequent use of stone; often the floors are made of opus signinum to facilitate cleaning. In order to make these operations easier, the possibility of finding fresh water was of primary importance, for this purpose rainwater was often conveyed from the roof, through compluvia, and then used during these operations.

Garum Trade in Mediterranean

By Grasso Riccardo

The notoriety and spread of garum throughout the Mediterranean area, especially in Roman times, is made evident not only by Classical sources, or numerous production centres, but also by the amphorae of various origins associated with the transport of this fish sauce. It is precisely their discovery, together with investigations confirming their contents, that indicate that the dish was not only consumed locally but was also exported for commercial purposes. Added to this is the fact that within the production facilities themselves there were spaces with a warehouse function in which the amphorae were stored, inside which the finished product may have been collected pending its distribution.

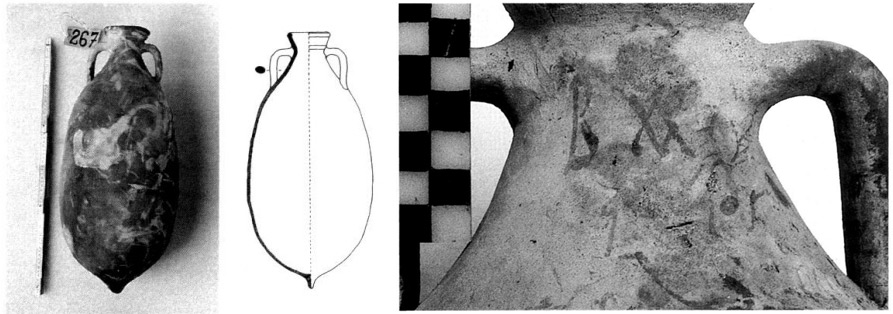

Evidence of the commercialisation of Garum is provided by the small amphorae called “Grado I” and found at the Grado wreck (Gorizia, Friuli- Venezia Giulia, Italy) of the 2nd A.D. measuring approximately 55/70 cm. in h., 30 cm. diameter and 17 litres in capacity. They have tituli picti (they are painted commercial inscriptions) on the neck and handles, including the term liq(uaminis) flos. Comparisons show strong similarities with the amphorae Dressel 6B type typically produced in the Upper Adriatic area, in the North- East part in Italian peninsula, of which they could therefore be a smaller variant of the “mother” forms (Auriemma, 2000, pp.34, 36- 45).

This type of small amphorae (See Figure 2) in the wreckage was found associated with various other types probably reused to contain preserved fish, not sauces. The widespread presence in other terrestrial contexts of the “mother” forms from which they derive, could therefore suggest the existence of a lively but circumscribed market for fish and fish products, such as Garum, in the area of Northern Italy and Transalpine (Auriemma, 2000, p.48).

On the other hand, fish sauces from the Iberian Peninsula, produced in centres such as Baelo Claudia (Cadiz, Andalusia, Spain) and Malaca (Malaga, Baetica, Spain) (Expòsito, Bernal Casasola and Diàz, 2018, pp.294-295) or Lusitania (Portugal), became more widespread, as evidenced by the wide distribution of Iberian amphorae throughout much of the Mediterranean. Examples of amphorae associated with this type of product include:

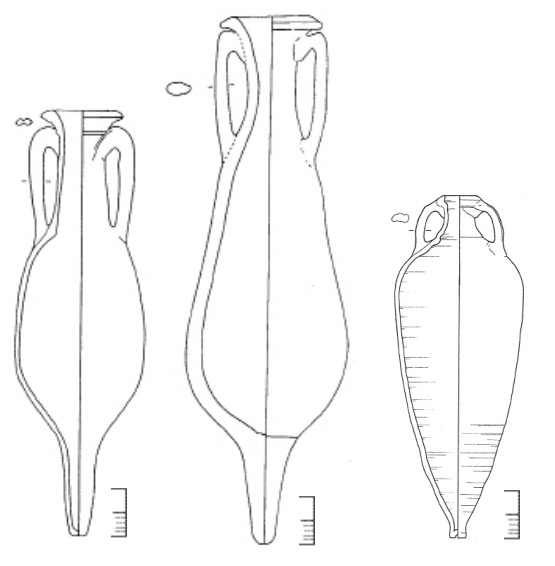

- Dressel 8: Made in Hispania Baetica, ovoid shape, h. 0.85/1.00 m. ca., high truncated cone neck joined to a short shoulder, rim well separated from the neck, ribbon or elliptical handles set below the rim and on the shoulder and with a high elbow, high and hollow bottom with cylindrical or truncated cone section and slightly convex tip. They date between the end of the 1st century BC and the second half of the 1st century AD. They are found not only in the Iberian Peninsula itself, but also in almost the entire western area of the Roman Empire and partly in the eastern Mediterranean (Bertoldi, 2012, p.47). In Italy, for example, some have been found in centres such as Villa Arianna in Stabia (Naples, Campania, Italy) (Federico, 2006, p.259);

- Beltràn IIB: Made in Hispania Baetica, pyriform body, ca. 1.10/1.20 m. h., high cylindrical neck with concave sides, short shoulder, solid and vertically banded loops with high elbow, truncated cone bottom. Dated 1st to early 3rd century AD, they were found mainly in the western European provinces, a little in North Africa and partly in the eastern areas of the Mediterranean (Bertoldi, 2012, p.54). In northern Italy, examples have been found at the Bedriacum site near Calvatone, close to Cremona, Lombardy (Ravasi, 2006, p.323);

- Almagro 51C: Made in Lusitania, pyriform body, h. 0.75 ca., truncated conical neck well separated from the body and higher than in the older A and B variants (where it was cylindrical), banded rim with hanging lip, flattened ribbon-like handles set on the rim and shoulder, small, hollow and cylindrical base (while in the A and B variants it was solid and conical) and rounded tip. Dated between the 4th and mid-5th century AD, they were widespread not only on the Iberian Peninsula, but also in Gaul and Italy, with a few finds in North Africa (Bertoldi, 2012, p.66). Some specimens have been found in central Italy, for example associated with 4th century AD phases at the site of S. Gaetano di Vada in Rossignano Marittimo at Livorno, Tuscany (Del Rio and Vallebona, 1996, p.491).

(See Figure 3)

The cases reported here represent well the extension of the Iberian trade routes during the Roman Imperial Age. As can be seen, in the first period exports touched practically all the western areas of the Empire and (although to a lesser extent) reached the eastern provinces. But it was precisely between the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd century AD, following the great upheavals caused by the crisis of the Middle Empire, that trade routes from the Iberian Peninsula progressively diminished and decreased in radius, in favour of North African products, which were to become predominant in trade routes throughout the Mediterranean until the conquest of the province by the Arabs in the 7th A.D. (Gianfrotta and Pomey, 980, p.164), following the latter's famous victory over the Eastern Empire at Yarmuch in 636 A.D. (Miotto, 2007, pp.22-23).

Among the most important African ceramic products used for fish sauces such as Garum are:

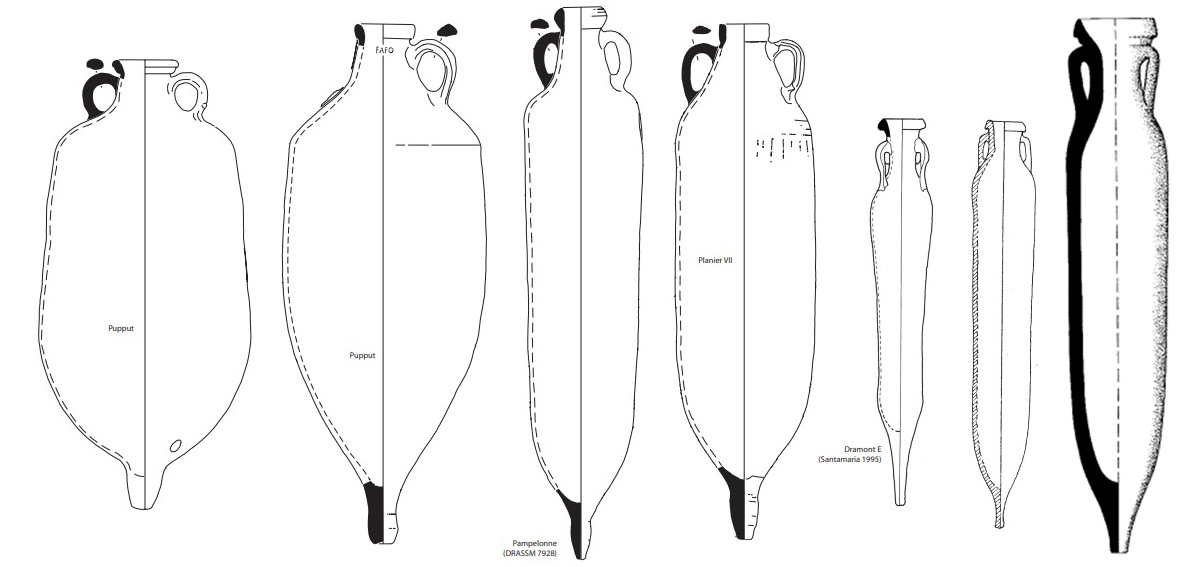

- African II: Made in the areas of northern Tunisia, there are several variants of this pottery between the middle of the 2nd and the end of the 3rd century AD (A and B types) and between the 3rd and about the middle of the 4th century AD (C and D types) (Bonifay, 2016, p.542). Cylindrical and elongated body, approximately 1.10/1.20 m. h., truncated conical neck, distinct rim and curved, rounded handles that are set on the neck and shoulders. They weigh about 17 kg when empty and can carry about the same amount of product as a Spanish Dressel 20. These characteristics undoubtedly influenced their increased diffusion during the 3rd century AD at the expense of the Iberian area (they carried both oil and fish sauces) (Gianfrotta and Pomey, 1980, p.165). Spread throughout the Mediterranean, there are finds such as those in Cagliari, near the port, in via Caprera and in vico III Lanusei (De Luca, 2019, p.639);

- Spatheion: Also produced in the Tunisian area, it has several types (1- 3), each of which corresponds to several sub classifications. In particular, type 1A is associated with the African IIIC for certain morphological characteristics. They can be dated between the first half of the 5th century AD (type 1), the second half of the 5th- 6th century AD (type 2) and the late 6th-second half of the 7th century AD (type 3). They have a cylindrical body, an elongated and narrow profile, a variable rim but generally with rounded profile projecting outwards, a long neck, handles generally inserted between the neck and the shoulder, and a base characterised by a truncated cone-shaped tip. They are widely disseminated in both the East and West (Bonifay, 2004, p.125-129). Specimens have been found in important wrecks such as Dramont E in Saint Raphael (France) (Santamaria, 1995, p.51) and Yassi Ada I (Turkey) (Bass and van Doorninck, 1982, p.182) or in contexts such as S. Eulalia (Cagliari, Sardinia) (De Luca, 2019, p.640).

(See Figure 4)

Here again, the examples of transport amphorae reported serve to give an overall idea of the wide diffusion of the African product throughout the Imperial period, further confirming its notoriety and fame, both along the Pars occidentalis and in the Pars Orientalis (western and eastern parts). Its marketing even over long distances was then undoubtedly due to the very high concentration of salt, widely used during the preparation of the sauce, to ensure its long preservation. It is no coincidence that the production plants were always strategically located near active salt pans, in order to constantly exploit this fundamental resource.

Experimental archaeology

By Mainetti Manuel

Experimental archaeology is a discipline that deals with recreating the ancient techniques used in antiquity in order to study how our ancestors lived, built, produced and transformed objects. It is a branch of archaeology that is based on the reconstruction of ancient processes in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the techniques used in the past. It is a fundamental discipline to better understand the past.

(See Figure 5)

The Experiment

Before describing the various phases of the experiment, we want to thank Giovanni Romano and the association Sardinia Romana both of who have made available to us both knowledge and skills, as well as materials to complete this experiment.

As we have seen earlier in this article, the historiography concerning the Garum, as well as the archaeological evidence of the same, are very wide and cover the entire topic both from the historical and archaeological points of view. Using these skills, we divided the experiment into several stages in order to be as historically accurate as possible.

But first of all, we have to start with the pivotal question that triggered this experiment; can a team of archaeologists faithfully recreate Garum today, starting only with the historical knowledge available to us, and at the same time being careful to use the methods and materials that the ancient Romans had at their disposal to make this product? Since this is a scientific experiment, it is only for academic demonstration and is not subject to the marketing of the finished product. This freedom allows us to answer the archaeological unknowns of production on the basis of the findings in the various excavations, and without in any way altering the original recipe for the purpose of sale. What did Garum taste like? What did it smell like? What colour did it have during its fermentation process and what consistency? These are the questions that cannot be answered without first carrying out a corresponding experiment.

The first step is the most important, on which the whole rest of the process depends: get a fish that lends itself to the release of a lot of blood and liquids, because Garum is basically produced from the liquids inside the fish.

- Phase one. Obtaining the historical ingredients, through the archaeometric analysis carried out by colleagues in different archaeological excavation sites, in places of production of the garum (Bernal Casasola, et al., 2016). We needed to factor in salt, spices, and especially fish. In this particular case, we identified anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) and mackerel (Scomber scombrus) for a total of 1.3kg of fish used during each experiment. (Pliny the Elder, Nat. His., 31.43 (par. 93-94)) As can be seen from Figs XYZ of phase one, we made the first preparation of the container with salt and spices (oregano, mint, sage, parsley, rosemary, thyme, fennel, and black pepper). We used 700g of salt in total and 20g for each individual spice to be divided later in the various layers. These should be ground at the bottom of the container. It is important to note that, from the various experiments carried out, we found that coarse salt was not used, but rather medium salt, freshly ground in a mortar. This is because coarse salt does not dissolve completely and affect the finished product (See Figures 6-10)

- Phase two. Once all the aromatic components, salt and various spices are ground and the first layer were created inside the container that will contain the fish, it then passes to phase two. This can be said to be the crudest phase of the whole process, but it is also the most interesting, because it allows us to understand the type of processing used to allow the flow of all internal juices. The fish are shredded, crushing those parts of the body where the greatest amount of fluids is contained. Then the head and intestines are processed. The cut is not done randomly but to preserve the internal organs of the fish. In this phase of the experiment, it is necessary to work well over a wooden tray in order to preserve those liquids that come out of the cut, and then drain those liquids left inside the container along with the processed fish. The fish now almost reduced to a pulp composed of large pieces, is then placed in the pot and then covered with previously mixed salt and spices, in a sufficient quantity to cover all the product in several layers of fish and salt during phase one. We continued in this way, creating a stratigraphy of salt, spices, and fish, until the container was completely full. Of course, it is important to remember that this being an experiment it was conducted on a moderate amount of product each experiment involved the use of 1.3kg of fish, so when we think about the production of Garum we must always remember that it was made in huge production tanks, but despite the small amount that we are analysing, this was still the method of creating the finished product (Carannante, 2008). Then returning to the experiment, once the container has reached the desired level of fullness, care was taken to create a sort of cap with salt and ground spices, ensuring that no piece of fish or liquid from it came into contact with the air, this procedure can be seen from the photos of the end of phase two (See Figures 11-13).

- Phase three. The raw product, stored in salt, is placed in the sun for at least 20 days. During the experiment, we realised that we had the foresight to cover or store in dry places in the evening to prevent any failure due to moisture. These had in the best finished product in terms of both preservation and product yield. In these samples we could observe that just after about 20 days of maceration the salt has lowered from the previously set level. Moreover, the surface crust made of the layer of salt exposed to the air changed from white to a reddish colour. This was an indicator that the liquid had begun to rise, dissolving the salt in the layers, and beginning the real processing (See Figures 14-15).

- Phase four. We must admit that phase four was the one that gave us the most problems, both from methodology and from the olfactory point of view. The product is mixed inside its container several times a day for a minimum of 20 days. This processing has a dual purpose, both to not dry the product, and to make it go bad, which also allows the best possible dissolution of salt. The process can be considered finished only and exclusively when the fish pulp reaches a level of semi-liquidity that allows the filtering of the liquid through special instruments. Our research team noticed during this phase of the experiment, that the samples left without mixing, although they produced a small amount of liquid, was not in the least comparable to the yield of liquid produced by the samples subject to daily mixing (See Figures 16-19).

- Phase five. This part of the experiment is comparable to modern bottling. This brings the finished matured product to the tables of the ancient Romans. The product is put through copper alloy strainers covered with pieces of cloth in order to filter it and separate the solid remains of fish, undissolved salt and pieces of spices and herbs. This process can be seen in the photos where initially the dark brown compound is pressed and filtered to obtain a light brown liquid. As a note to this experiment, the research team must affirm that the odours arising from the final phase of the product, are not at all unpleasant. On the contrary, the product is like the smell of anchovy paste and anchovy casting, available today in markets. So, we have to initially dispel the myth that the finished Garum, not the one being processed, understood as phase 2 and 3, was foul smelling. Indeed, it lends itself very well to seasoning on different types of dishes. The residual liquid of this filtration is the Garum floss times and the flower of the finished product. It was the most commercially valuable product in ancient times (Dolciotti, Panella and Cerchiai, 1999, pp.57-58) (See Figures 20-28).

- The remainder looks like a sort of coarse paste, due to the continuous friction of the mixing of phase four, it is called Allec (or Hallec). Citing historical sources, we have good knowledge that although it was not entirely disdained, it was not fully appreciated on the tables of the rich. Indeed, being much cheaper than sauce itself, and being recognised as less valuable, it was recommended for feeding rural slaves (Cato the Censor, De Agricultura, 58) (See Figure 29).

Stage five is intended primarily as a preparation for the placing on the market of the finished product. The bottling in amphorae or glass bottles for smaller quantities, was absolutely important for preservation and to allow the product to be decanted. The product was in almost-hermetically sealed containers. At the end of this phase, we must make two notes about this stage of the experiment itself, the first, which, as mentioned above, the finished product is suitable for use on different types of food and we can say that at a first taste, always with scientific purpose, the taste is not at all different to today’s fish products mentioned above. For example, Garum is excellent spread over meat (Botte, 2009), before or after roasting it over live coals, or cooked in some other way. It is also excellent with mainly wild herbs such as lettuce, borage, chard, cooked or raw, seasoned with oil and vinegar. We have also experimented with it in various legume soups and in the mixture of meatballs, and to accompany lightly salted boiled eggs. It is also excellent in omelettes with asparagus and artichokes, and is of course absolutely palatable when accompanied by bread of any kind. It is even more palatable when mixed with good olive oil to create an exceptional flavour mix. Finally, we have also tried it on fish. In particular, it goes well with sea bream (Sparus aurata) also cooked on the grill. Of course, the criteria used to evaluate this conclusion are those governing culinary sensory, i.e. the visual, olfactory, taste and texture aspects of the food ingested. Although the last one is subject to the main food with which Garum is accompanied, the other three characteristics, tested on a sample of 6 people, fully satisfy each of them as regards the taste of Garum combined with the various foods presented. The second point that we must make, is that concerning the state of decantation of the finished product, leaving it to rest inside a glass bottle, we have been able to observe that if left stationary for approximately between 5 and 7 days, all the micro residues that inevitably pass through the filtering process, settle in the lower part of the bottle. This also affects the colour spectrum of the finished product, going from a light brown on top and to a dark brown, tending to grey for the solid part deposited on the bottom, The liquid in suspension takes on a thin light reddish colour. Of course, we noticed that this sort of decanting does not affect the taste of the finished product and subsequently the taste does not vary.

In the end, we can say that despite everything, by following a few small tricks, it is possible to recreate garum from historical and archaeological sources.

The experiment itself was carried out by a team of four people, the authors of the article. As already written, the hypotheses and objectives were clear from the start: to obtain a palatable and edible product. We therefore needed to carry out an experiment based on direct manipulation of the subjects (as opposed to observational experiments, where we simply examine what happens in nature and to what extent). We therefore proceeded with the experiments on our samples, in this case fish, salt and the various spices above, which were subjected to different stimuli without first knowing in detail what reaction or result we would obtain.

This research team then decided to clarify exactly what would be the experimental factors and thus the stimuli to which the experimental units (Air, Water, Heat, Sun Rays) would be subjected and different processing of the raw materials already described by ancient historians.

For example, if the objective is to assess the effect of temperature on the maturation of Garum, the experimental factor will be the temperature and the hours to which the terracotta jar will be subjected, and the relative days of exposure to which the various samples considered will be subjected.

But going into more detail, we have noted down the various types of results in precisely 5 samples; the variations in the experiment and how they were obtained are the result of a general test whose objective was to obtain an edible and palatable product, and just as written above, the optimum result sought should be represented by precisely these two factors.

Sample 1a: The coarse salt did not dissolve completely or produce the fish liquid correctly. By 'properly', we mean that it did not generate enough product to give value to the raw materials used. Consequently, it would probably not have been economical to process in large quantities.

Sample 1b: The fish is processed coarsely, so the blood and entrails of the fish do not escape completely and sufficient liquid quantities are not obtained to trigger the salt dissolving process. At the end of the process, the fish appears dry, almost like salted fish.

Sample 1c: The salt cap on the container was not done correctly, exposing the liquid and parts of the fish to the action of the air. The product was rotten, the smell was clearly that of rotten fish, and no one dared to taste it.

Sample 1d: We must also note a variation which occurred due to the quality of the fish, sample 1c was made using a poor-quality fish, although of the same type as the fish used in the other experiments, this fish was low in fat and blood, we assume not fresh or subjected to various freeze-thaw cycles and therefore the yield of the product was compromised by the absence of the adipose-blood liquids essential for generating the Garum. At the end of the experiment the fish was totally dry.

Bibliography

Auriemma, R., 2000. Le anfore del relitto di Grado e il loro contenuto. Mélanges de l'École française de Rome: Antiquité, 112(1), p.27-51.

Bass, G. and van Doorninck, F.H., 1982. Yassi Ada. Volume I. A seven- century Byzantine Shipwreck, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, p.182.

Bernal Casasola, D., García Vargas, E., 2014. Talleres haliéuticos en la Hispania Romana, in Bustamante Álvarez, M., Bernal Casasola, D., Artífices idóneos Artesanos, talleres y manufacturas en Hispania, Mérida: Editorial CSIC, p.295-315.

Bernal Casasola, D., Marlasca, R., Rodríguez Santana, C.G., Ruiz Zapata, B., Gil García, M.J. and Alba, M., 2016. Garum de sardinas en Augusta Emerita. Caracterización arqueológica, epigráfica, ictiológica y palinológica del contenido de un ánfora Beltrán IIB. Rei Cretariae Romanae Fautorum Acta, 44, p.737-749.

Bertoldi, T., 2012. Guida alle anfore romane di età imperiale. Forme, impasti e distribuzione. Rome: Espera, p.47-54- 66.

Bonifay, M., 2004. Etudes sur la céramique romaine tardive d’Afrique. BAR International Series 1301, Oxford: Archaeopress, p.125- 129.

Bonifay, M., 2016. Eléments de typologie des céramiques de l’Afrique romaine. In: D. Malfitana and M. Bonifay, eds. 2016. La ceramica Africana nella Sicilia romana. Tomo II. Catania: CNR-IBAM. p.507-575.

Botte, E., 2009. Le Dressel 21-22: anfore da pesce tirreniche dell’alto impero. In: S. Pesavento Mattioli and M.-B. Carre, eds. 2009. Olio e pesce in epoca romana. Produzione e commercio nelle regioni dell’Alto Adriatico. Atti del Convegno (Padova, 16 febbraio 2007). Rome: Quasar. p.149-172.

Campos Carrasco, J.M., 2011. Aestuaria. Una ciudad portuaria en los confines de la Bética. Huelva: Concejalía de Cultura, p.55-91

Carannante, A., 2008. L’ultimo garum di Pompei. Analisi archeozoologiche sui resti di pesce della cosiddetta Officina del garum. Automata. Rivista di natura, scienza e tecnica del mondo antico. Journal of nature, science and technics in the ancient world, 3/4, p.43-53.

Cato the Elder., 1964. Marci Porcii Catonis Liber de agricultura, Roma: Ramo editoriale degli agricoltori.

De Luca, G., 2019. Anfore tardo- antiche a Cagliari: produzioni africane e iberiche (II- VII secolo). In: R. Martorelli, ed. 2019. Know the sea to live the sea. Conoscere il mare per vivere il mare. Atti del Convegno (Cagliari – Cittadella dei Musei, Aula Coroneo, 7-9 marzo 2019). Perugia: Morlacchi Editore. p.635-648.

Del Rio, A. and Vallebona, M., 1996. Le anfore (IV-VI/VII sec.) rinvenute negli horrea di S. Gaetano di Vada (Rosignano M.mo, LI): ricerche archeometriche, morfologiche, quantitative. In: P. Moscati, ed. 1996. III International Symposium on Computing and Archaeology (Roma 22-25 Novembre 1995). Archeologia e Calcolatori 7. Florence: Edizione All’Insegna del Giglio. p 487-496.

Dioscorides, P. and Marcellus Vergilius., 2012. Pedacii Dioscoridae Anazarbei De Medica Materia Libri Sex, 2012.

Dolciotti, A.M, Panella, C. and Cerchiai, C., 1999. Attività italiana all’estero. Leptis Magna. Un’anfora e il suo contenuto. Garum o allec? Bollettino di archeologia, 57-58, p.169-173.

Edmondson, J., 1987. Two industries in roman Lusitania – mining and garum production. Bar International Series 362, Oxford: BAR Publishing, p.102-124.

Edmondson, J., 1990. Le garum en Lusitanie urbaine et rurale: hiérarchies de demande et de production, in Gorges, J. G., Les villes de Lusitanie romaine, Hiérarchies et territoires, Table ronde internationale du CNRS (Talence, le 8-9 décembre 1988), Paris: Presses du CNRS, p.123-147.

Expòsito, J.A., Bernal Casasola, D. and Diàz, J.J., 2018. The urban halieutic workshops of Baelo Claudia (Baetica, Hispania). In: V. Caminneci, M.C. Parello and M.S. Rizzo, eds. 2018. La città che produce. Archeologia della produzione negli spazi urbani. Atti delle Giornate Gregoriane X Edizione (10-11 Dicembre 2016). Bari: EdiPuglia. p.289-296.

Federico, R., 2006. Contenitori da garum e consumi alimentari a Villa Arianna di Stabiae: alcune considerazioni. In: L. Lagóstena, D. Bernal and A. Arévalo, eds. 2007. Ceteriae 2005: Salsas y Salazones de Pescado en Occidente durante la Antigüedad. Actas del Congreso Internacional. BAR International Series 1686. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz. p.255- 264- 270.

García Vargas, E. and Bernal Casasola, D., 2009. Roma y la producción de garum y salsamenta en la costa meridional de Hispania. Estado actual de la investigación. In: D. Bernal Casasola, ed. 2009. Arqueologia de la pesca en el estrecho d Gibraltar de la Prehistoria al fin del Mundo Antiguo. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz. p.133-181

Gianfrotta, P.A. and Pomey, P., 1980. Archeologia Subacquea. Storia, tecniche, scoperte e relitti. Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, p.164-165.

Isodoro of Sevilla., 2004. Etymologiae, ed. by Angelo Valastro Canale, Torino: UTET.

Martial., 2021. Epigrammi, ed. by Giuseppe Norcio, Torino: UTET.

Milham Mary Ella., 1969. Apicii decem libri qui dicuntur De re coquinaria, Lipsia: Teubner.

Miotto, M., 2007. Bisanzio e la difesa della Siria: Arabi Foederati, incursioni arabe e conquista islamica (IV-VII d.C.). Porphyra, 4(10), p.5-28.

Petronius Arbiter., 2015. Satyricon, ed. by Monica Longobardi, Milano: Rusconi libri.

Pseudo Rufio Festo., 1874. Rufi Festi Breviarium rerum gestarum, rec. W. Föerster, Vindobonae, Hoelder.

Pliny the Elder., 1997. Storia Naturale, Torino: edizioni Einaudi.

Ponsich, M., 1988. Aceite de Oliva y Salazones de pescado. Factores geo-económicos de Bética y Tingitania, Madrid: Editorial Complutense, p.153 image 82.

Ravasi, T., 2006. Olio, vino, garum. Le relazioni commerciali di Calvatone-Bedriacum alla luce dei ritrovamenti di anfore. In: D. Malfitana, J. Poblome and J. Lund, eds. 2006. Old Pottery in a new Century. Innovating Perspectives on roman Pottery Studies. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi (Catania 22-24 Aprile 2004). Catania: Istituto per i beni archeologici e monumentali. p. 315-330.

Santamaria, C., 1995. L'épave Dramont « E » à Saint-Raphaël (V siècle ap. J.-C.). Archaeonautica 13. Paris: CNRS Éditions, p. 51.

Seneca the Younger., 2021. Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, Arma Virumque.

Silva, C.T., Soares, J. and Coelho-Soares, A., 1992. Estabelecemento de produção de salga da época romana na Quinta do Marim (Olhão). Resultados preliminares das escavações 1988-1989. Setúbal Arqueológica, 9-10, p.335-374.