The lack of metal lorinery in the archaeological record of early medieval Ireland is addressed through a hypothesis that post-Iron Age bridles were made of straw and rushes, which did not survive deposition. Reconstruction and testing of a straw bridle show the material to be strong and quite suitable for vernacular use. It also raises questions as to the agency of using straw instead of leather, and what this may tell us of the techno-cultural transitions each side of Ireland's Iron Age.

Introduction

The scarcity of metal tack in the archaeological record of Ireland's early medieval period (AD 450 to 800) has presented something of a puzzle for archaeologists. The ubiquitous Dr Finbar McCormick (2007, p.93) has remarked that if it was not for ample references in Irish literature, legal tracts and carved images of equitation on High Crosses and churches across Ireland, one would suspect that very few equids existed on the island.

The art of the loriner had flourished during Ireland's Late Iron Age (c.800 BC to AD 450; see Maguire, 2021), with copper alloy ported snaffles which were more sophisticated than any of their contemporaries in Europe or Asia. Tack has been one of the more regularly found objects of the elusive Irish Iron Age, with over 200 specimens known within the archaeological record. This makes the lack of manufacturing continuity into the early medieval period even more curious. Bit styles, unlike many other objects encountered by archaeologists, almost always have analogues in different eras. It is as if the technology which created the sophisticated copper alloy snaffles and bosals of Irish late antiquity just ceased to exist after the third or fourth century AD, as the metal bits of the early medieval period which have been found are basic single jointed snaffles, like those which have existed across Europe and Eurasia from the Bronze Age.

There is some evidence of repairs and subsequent reuse on some of the Irish Iron Age specimens, but eventually, the skills of the past appear to have been abandoned. The manufacture and use of iron became more prevalent through the early medieval period, resulting in damaged objects being melted down and made into other things. Even allowing for the reality of constant recycling, there is still a paucity of equestrian equipment from AD400 to 800. The only logical reason for such an absence would be if, unlike metal, the materials used in manufacture did not withstand centuries of deposition in soil.

The IRC Government of Ireland Postdoctoral project, 'Making Time', hosted by University College Dublin, seeks to identify where technological changes occur throughout the Irish Iron Age, and by doing so, define and tighten the chronology of the period, which has been a constant issue within Irish archaeology. To date, researchers have been looking for changes from alloy to alloy, whereas we argue that attention must be paid to use of other materials to refine a chronology based on technology. Noting the scant artefactual collection of early medieval tack, compared to that of the Late Iron Age, it has been considered that this significant change in how things were being made merits analysis. This was presented at the EXARC session at EAA conference, Belfast on September 1st, 2023. This paper deals purely with the experimental archaeology aspect of the research, while papers currently in preparation examine the archaeology of the social and ideological agency behind choices of materials.

Setting the scene: early medieval Ireland

Ireland of the early medieval period (AD 450 to 800) was a highly structured society. We know this from legal texts such as the Senchus Mor, Críth Gablach and Breatha Comathcesa (ALOI) which contain laws and legislations which controlled almost every aspect of daily life. These civic instructions were collated and recorded between the seventh and eighth centuries AD (Higgins, 2011, p.194), although there is a possibility some may be several centuries earlier (Graf, 2016). Affluence was measured in livestock, with a designated allowance of what animals could be kept, according to status. In the case of the ócaire, a lower freeman classes, the law allowed "a horse for both working and riding" (ALOI 4, 1879, p.305).

Bridles were important displays of status and prosperity. There are detailed compensations for use of a bridle loaned by someone from a higher social class than the borrower (ALOI 5, 1901, p.417). There is a telling quote in the Crith Gablach stating that a chieftain was expected to have "a riding steed becoming his rank, with a silver bridle. Four steeds has he besides, with green bridles" (ALOI 4, 1879, p.323), which appears to indicate bridles made of rushes or straw, ie greenery. To date, no silver lorinery has been found in early medieval contexts. The free landowner, the bóaire, was expected to have an enamelled (cruan) bridle for his riding horse (ALOI 4, 1879, p.311). Enamelled bridles are also mentioned in the Togail Bruidne Da Derga (a supernatural saga, with identifiable Iron Age influences), only on British invaders' ponies (Koch and Carey, 2003, p.175), despite this kind of decoration being much more associated with the Late Iron Age. Only one early medieval example with champlevé is known, from Killeevan, County Monaghan (Maguire, 2021, UCB2, p.131), and is an object with a complex biography of reuse and repair.

The use of straw and rushes in early medieval Irish harness

One of the rulings within the legal texts mentioned states that horses must be fettered or stabled in suitable structures and not allowed to wander onto neighbour's land, requiring "eich I cuib rech teachta na na ninde [ … horses tethered in their proper fetters or in a stable]" (ALOI 4, 1865, p.105). Spancels, or hobbles, were made with plaited straw to prevent horses and ponies straying (Stokes, 1895, pp.36-37; Gwynn, 1924, pp.24-25), something which was very much disapproved of legally. The same set of texts also refer to "hair bits" and "osier withes" (ALOI 1, 1901, p.175) being used as mouthpieces of bits, which were attached to leg fetters to prevent wandering.

It is important to remember that while these texts substantiate the use of such 'soft' vernacular bits, such mouthpieces had been used from the beginnings of equitation in Europe and Eurasia. The remarkably (arguably miraculous) well-preserved Late Bronze Age harness from Baekkedal, Denmark included mouthpieces made of twisted and plaited straw, decorated with metal connectors and fastenings at junctions on the bridle, such as phalera on the browband, and metal cheekpieces (Sarauw, 2015).

Straw and rushes were renewable resources for any agricultural people of the past and equipment made from them could be as efficient as any more permanent material. O'Dowd (2015, p.344) detailed complete sets of harness, as well as hybrid riding/pack saddles (referred to afterwards as súgáns) and even stirrups being made of straw. Several early medieval Pictish stones in eastern Scotland, such as the Hilton of Cadbol and Kirriemuir stones (See Figure 1 with detail highlighted), also show plaited or woven textured súgáns, informing that this practice occurred in Scotland as well as Ireland, leaving the possibility it was also used elsewhere in Europe, for no technology or craft occurs in a vacuum. It is also likely this folkcraft existed in Ireland's Iron Age, contemporary with the elite copper alloy snaffles. We can speculate that perhaps such equipment was for the slightly less affluent, but there is no genuine way of discerning this.

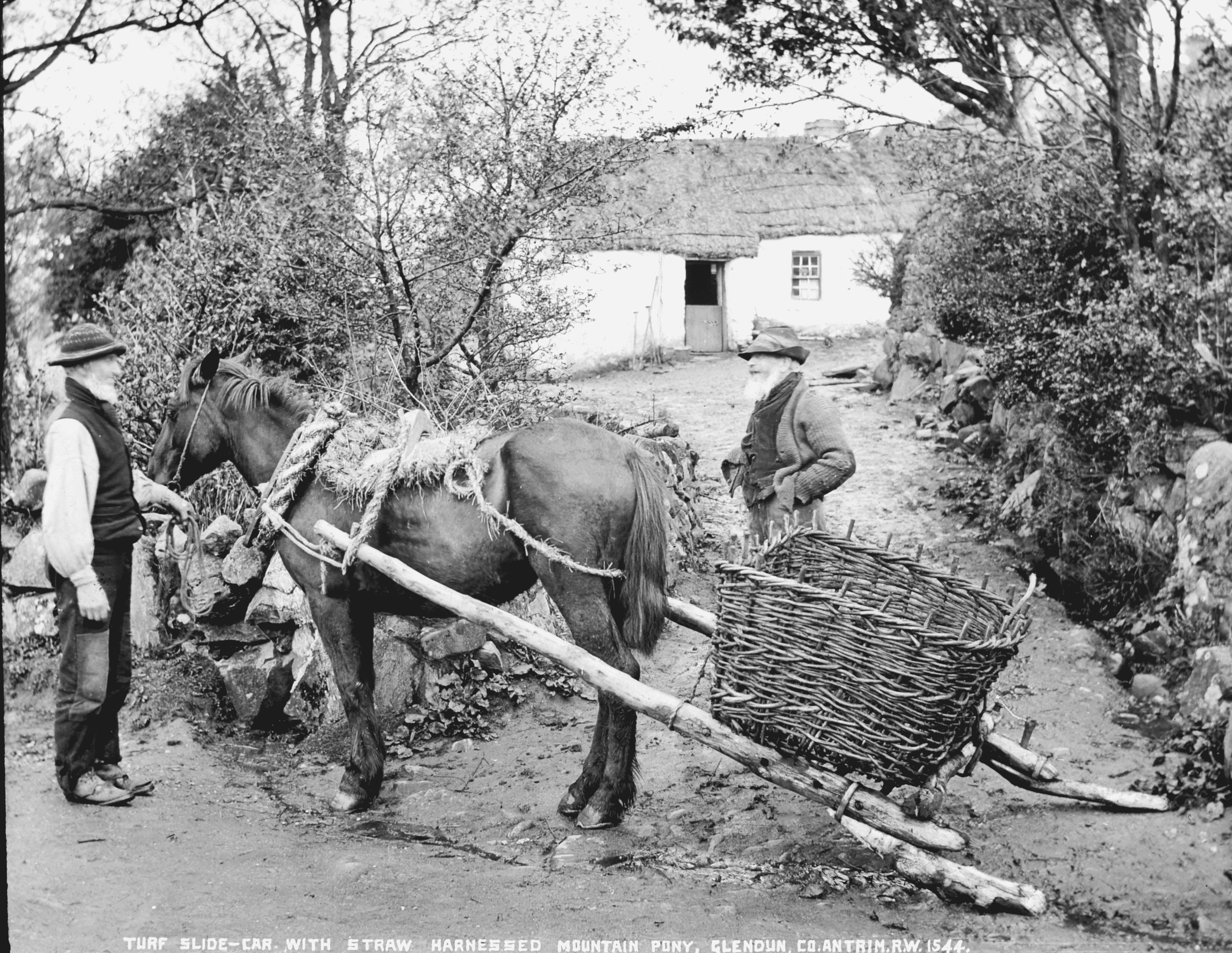

The craft continued well into the early modern world, with paintings of straw harness fitted to garrons (small working horses) in Hillsborough, County Down in the eighteenth century1, while the displays of vernacular carts and vehicles at the 'Land Sea and Sky' display in the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum of Cultra, County Down, has plentiful images of hardy Cushendall Hill Ponies harnessed with straw traces and bridles, and even adapted súgáns for draft saddles (See Figure 2) pulling small carts and travois loaded with turf.

From Moynagh to Mayo: reconstructing organic harnesses

Ireland's Bronze Age has a similar lack of equestrian material - we know there are equids on the island, but only have scraps of potential tack fragments to suggest domestication. Because of this, a speculative interpretation of an organic bridle (See Figure 3) was made with the results published in EXARC (Maguire, 2019), based on the Bronze Age antler cheek-piece found at Moynagh Lough, County Meath (Bradley, 1991) to test a colleague's hypotheses of Bronze Age equitation in Ireland (Scott, 2019). Its creation and testing answered some questions about function, endurance and strength of using antler within a bridle assemblage. It was found to be an efficient bridle but the animal would have been trained specifically to the use of it, as modern ponies treated the subtle communications via rein with considerable contempt, having being trained to the immediacy of metal bitting. This was much more akin to riding using a halter or headcollar - something most 'horsie' people have done occasionally! Equitation in Ireland's Bronze Age was very different, then, from the kaleidoscope of later external influences which produced the tack of the Iron Age elites.

Making and using a plaited straw bridle

The decision was made to recreate a complete plaited straw bridle, for both experiential and experimental archaeological information. No early medieval/medieval organic bridles or súgáns survive, and full sets of straw harness from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are rare, although some do exist. The National Museum of Northern Ireland holds a beautifully crafted nineteenth century donkey bridle and breastplate from Armagh (See Figure 4), complete with blinkers. This example looked a little overambitious for a beginner, so the more basic example from County Mayo, in the collections of The National Museum of Ireland's Country Life collections (Cat No 12.64) in Castlebar became the basis for our reconstruction.

Consultation was made with Bob Johnston, a professional basket maker and living history demonstrator at Ulster Folk Museum, Cultra, County Down, as to how to make straw rope. Mr Johnston has extensive experience of folkcrafts, making wicker and straw masks for the popular Armagh Mummers of Northern Ireland.

Rye straw was used for this undertaking, as it is strong and pliable. The straw was sprayed lightly with water before working them, to increase pliability and decrease breakage. The method used to plait them is intuitive, with a handful of sheaves looped into a hook driven into a firm surface, to hold the tension of the plait as it becomes longer. The sheaves were divided into three bunches, with the right-hand side bunch twisted to the left before becoming the centre strand. The left bunch was twisted to the right as it then became the centre, and this was repeated, pulling, and tightening the rope as it grew in length. Extra sheaves were then spliced in as the rope grew in length (See Figure 5).

Using this technique, the components of a bridle were made separately- noseband, browband, cheekpiece/headpiece and throat lash. The throat lash was made of hemp twine, as working on the premise of using no metal components, a solution to a buckle fastening had to be found. The twine was light but strong and could be inserted into the upper cheekpiece with a slipknot, allowing for flexibility of fit. The components were sewn together with hemp twine, with the realisation that any kind of ancient bridle or headstall would benefit from decorative phalera to hide the 'messy' sewn connective parts (See Figure 6).

The first impression was just how strong the material was: it maintained integrity despite leaning full weight on it while it was attached to a door handle. One of the questions which needed addressed was just how much weight a plaited straw rope could actually take. As this was experimental work, we felt that use of an equid would not be ethical, as the tensile strength of the straw was unknown, and a breakage could endanger a draft pony. Modern animals are trained to respond to metal bitting, and as such, should breakage occur while using a straw bridle and no bit, the reaction of a pony could prove to be an unpredictable and potentially dangerous factor, especially when considering the testing of the Moynagh bridle some years ago, as mentioned earlier. Instead, a controlled experiment was set up in a secure space, with a metal shopping trolley and increasing loads of quantifiable weight, in this case, multi-packs of 24 tins of a soft drink brand. The trolley was estimated to weigh some 29kg itself, each weight increment was 8.6kg. Two thick plaited straw ropes were looped and knotted to the trolley, and used to pull it up a gentle gradient, then returning to accept a new addition to the load.

The average modern (nineteenth century to present day) curricle or dog-cart weighs on average some 90-100kg and can be reasonably easily pulled by an adult human. The trolley pulled by straw ropes easily accommodated a load of 16 by 8.6kg packages, plus the 29kg trolley, a total of just over 166kg. The author became uncomfortable with pulling the trolley up the gradient as the weights increased, so heavier loads could be potentially tested with extra participants. The ropes showed no signs of fraying with steady use, but alternative experimentation by Robert Johnston indicated that sudden breakage could occur with sudden jerky movements.

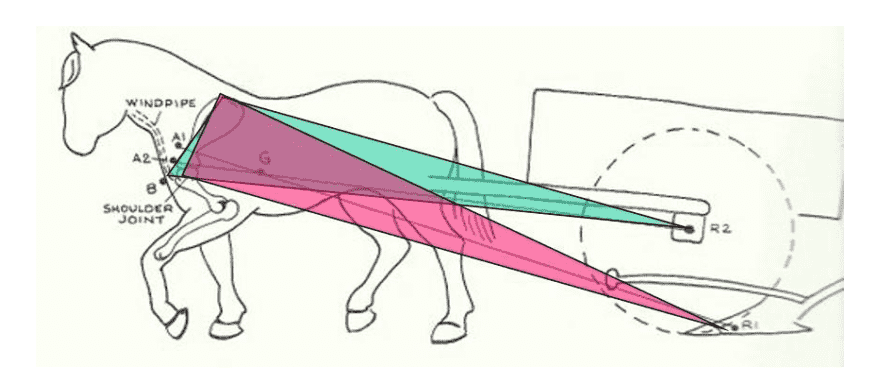

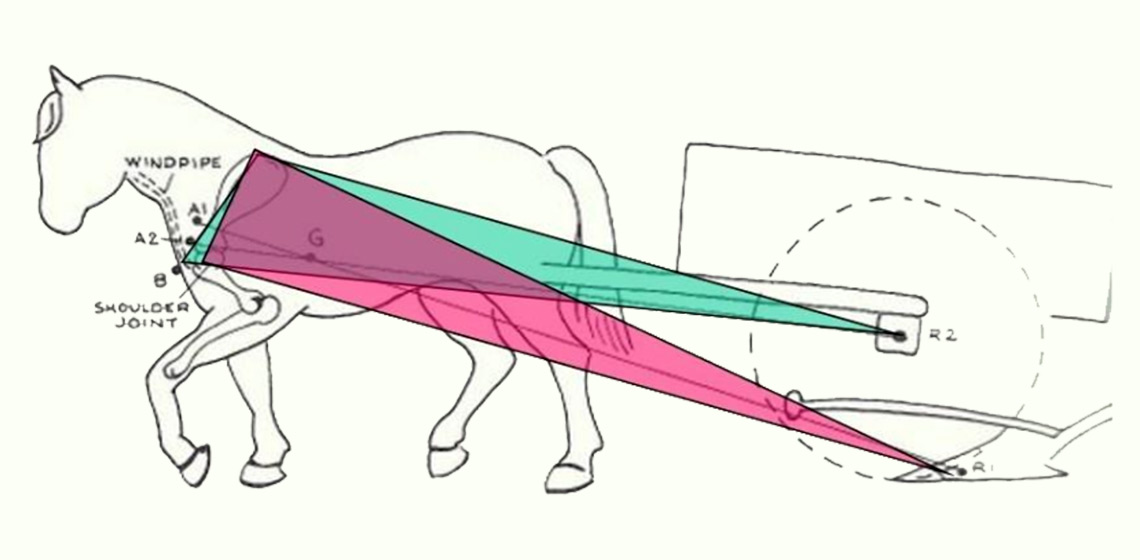

A small pony between 11 and 13hh (11.8cm to 132.1cm at the shoulder, or withers), which is around the size of the animals in the images can pull a cart with a load of over 350kg although the weight is distributed across the various traces and connectors to the vehicle. The areas of pressure exerted are at the chest and shoulder joint (Davis, 2021). The efficiency of moving a vehicle is known as the 'point of draught'. Horses do not actually pull draught - they push against a collar (See Figure 7) from their hindquarters with their full body weight. The pressure of a harness then is maximised in the collar, and not the traces. The straw rope which was used in the traces and as the pack saddle do not take the brunt of the point of draught. Straw collars were also made (See Figure 8 ) , and are remarkably strong constructions. Even modern leather full neck collars are stuffed with straw for comfort and can be repadded when they eventually flatten after a few decades.

Discussion

The option of straw and rushes remained a common means to accomplishing daily tasks from the early medieval period to the twentieth century, with evidence of improvisations depending on resources in both Ireland's rural regions, and Scotland's remote islands (MacDonald 1933; Holliday, 2017). It is very much against the odds that such tack components would survive deposition, and even if fragments were found, they may not be recognised for what they were.

It is understandable how such materials may have become the only option of the less affluent during the post-medieval period, as the themes of politics and poverty are omnipresent in Irish post-medieval history. However, leather and hide products were readily available in protohistoric and early medieval Ireland, especially considering the economic importance of livestock. The use of plaited straw rope would appear to be, for whatever reason, a deliberate choice.

For once, perhaps, we need to give some credence to that notorious early hibernophobe, Giraldus Cambrensis, who described the Irish method of riding with some horror (but then, almost everything Cambrensis witnessed in Ireland did that anyway). He stated that "They use reins which serve the purpose both of a bridle and a bit, and do not prevent the horses from feeding" (Cambrensis, 2000, p.69), quite a good description of an organic straw bridle.

This is a very different style of equitation from that of the Late Iron Age, which was closer to modern lorinery. Both the leather and twine bridle based on the Late Bronze Age Moynagh antler cheek piece and the early medieval straw halter functioned as modern bitless bridles do, indicating that early medieval equestrians relied on seat, voice and legs for communication with their mounts more than hands on reins.

The lavish double-jointed snaffles and bosals of Late Iron Age Ireland reflected the priorities of an elite who held a worldview (and self-view) which was obviously very different from both their predecessors and successors, and very possibly from their less-affluent contemporaries as well. The craft of straw-work apparently never went away after the early medieval re-emergence but continued, for economic reasons, well into the early twentieth century. The diminished manufacture of metal tack and an increase in the use of organic materials at some stage after the third centuries AD offers not just a technological boundary between the Iron Age and the early medieval, which has not been considered before, but also a glimpse at societal change in the longue durée. During this research we found many overlooked references to medieval and early modern use of straw and rushes for equestrian equipment, and we are interested particularly in reconstructing and testing possible saddlery solutions. This is also an area of interest to several academic colleagues in Scotland. The experiment as detailed here highlighted thinking outside the box and applying what old texts and images tell us, as well as how important folkcraft knowledge, experimental/experiential archaeology and material culture studies are to the researcher, to produce valuable insights to the past by actively doing and experiencing activities.

Acknowledgments: Our thanks to the curatorial staff of Ulster Folk Museum, Cultra, Co Down, without whose generous help and participation this paper would not be possible.

Note: The Ulster Folk Museum, known to most in Northern Ireland simply as 'Cultra', was Created by an Act of Parliament in 1958, the Folk Museum was created to preserve a rural way of life in danger of disappearing forever due to increasing urbanisation and industrialisation in Northern Ireland. The Folk Museum is located on the northeast coast of Ulster, in a village called Cultra. It houses a variety of old buildings, some of which have been relocated and rebuilt brick by brick from different parts of Ireland. Regular demonstrations of traditional crafts such as smithing, basketweaving, weaving and Irish cooking take place on site, preserving skills and encouraging their survival. Rare breeds of Irish farming animals are also present on site.

The museum holds the BBC Northern Ireland archive of radio and television programmes and possesses over 2,000 hours of sound material broadcast between 1972 and 2002 by the Irish language radio station RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta. The museum also maintains an archive of Ulster dialects, preserving identities which have become increasingly blurred with modernisation and gentrification.

- 1

See https://collections.nationalmuseumsni.org/object-belum-y-w-05-99-1

![]()

Glossary

Curricle: a light, open, two-wheeled carriage pulled by two horses, side by side

Dog cart: a small two-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle pulled by a single horse in shafts or driven tandem.

Hands high (hh): The hand is a traditional unit of measurement of length standardised to 4 inches (10.2 cm). It is used to measure the height of horses up to their shoulders, or withers.

Headcollar/halter: A bitless headpiece for leading or tethering a horse.

Lorinery: The term for manufactured small metal components used in driving harness and equestrian equipment.

Phalera: Decorative metal ornament fitted to harness, bridles or personal wear.

Snaffle: A snaffle bit is the most common type of bit used while riding horses. It consists of a jointed mouthpiece with a ring on each side and acts with direct pressure on the mouth and neck. It can have one or two joints.

Spancel: a contraption to fetter horses or other animals, often tied to the feet or legs.

Traces: Traces are the connective ropes or leathers which join the shafts of a vehicle to the horse.

Travois: A slide cart, with no wheels, more like a sledge

![]()

Bibliography

(ALOI) Ancient Laws of Ireland,volume 1, 1865. Translated by J. O'Donovan. Dublin: Alexander Thom.

(ALOI) Ancient Laws of Ireland, volume 4, 1879. Translated by W.N. Hancock, T. OʼMahony, G.A. Richey and R. Atkinson. Dublin: Stationery Office.

(ALOI) Ancient Laws of Ireland, volume 5, 1901. Translated by W.N. Hancock, T. OʼMahony, G.A. Richey and R. Atkinson. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Bradley, J., 1991. Excavations at Moynagh Lough, County Meath. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 121, pp.5-26.

Cambrensis, G., 2000, The Topography of Ireland. Translated by J. Forester. Ontario: In Parenthesis publications.

Davis, T., 2021. Harnessing Horsepower: then and now. In: R. Maguire and A. Ropa, eds. 2021. The Liminal Horse. Budapest: Trivent Publishing, pp.177-196.

Graf, S., 2016. Begrudgery and Brehon Law: A Literary Examination of the Roots of Resentment in Pre-Modern Ireland. World, 3(1), pp.62-77.

Gwynn, E., 1924. The Metrical Dindsenchas IV, Dublin: Royal Irish Academy Todd Lecture Series.

Higgins, N., 2011. The lost legal system: pre-Common Law Ireland and the Brehon Law. In: D. Frenkel, ed. 2011. Legal Theory Practice and Education. Athens: Athens Institute for Education and Research. pp.193-205.

Holliday, J., 2017. A wooden and rope bridle for tethering a horse. [online] Available at: <http://www.aniodhlann.org.uk/object/2007-9-2/ > [ Accessed 30 November 2023].

Koch, J. and Carey, J., 2003. The Celtic Heroic Age. Aberystwyth: Celtic Studies Publications.

Stokes, W., 1895. The Rennes Dindsenchas. Revue Celtique, 16, pp.36-37.

MacDonald, J., 1933. Highland Ponies and Some Reminiscences of Highlandmen. Edinburgh: Mackay.

Maguire, R. 2019. Lets do the tine warp again. EXARC, 2019/3 Available at: <https://exarc.net/issue-2019-3/at/lets-do-tine-warp-again> [Accessed 2 January 2024].

Maguire, R., 2021. Irish Late Iron Age equestrian equipment in its insular and Continental context. Oxford: Archaeopress.

McCormick, F., 2007. The horse in early Ireland. Anthropozoologica, 42(1), pp.85-104.

O'Dowd, A., 2015. Straw, hay and rushes in Irish folk tradition. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

Sarauw, T., 2015. The Late Bronze Age hoard from Bækkedal, Denmark-new evidence for the use of two-horse teams and bridles. Danish Journal of Archaeology, 4(1), pp.3-20.

Scott, B.G., 2019. Some notes on horse riding in the Irish Later Bronze Age. Journal of Irish Archaeology, XXVIII, pp.17-48.