The content is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License.

Unreviewed Mixed Matters Article:

Conference Review: Experiment and Experience: Ancient Egypt in the Present

Experiment and Experience: Ancient Egypt in the Present was held at the University of Wales, Swansea, by The Egypt Centre and The Department of History the 10-12 May 2010. The aim of the conference was to highlight both experimental research, and the value of experience gained through working with ancient materials and techniques. In addition to conventional papers, participants were encouraged to include physical demonstrations. The conference was also made available to a wider audience by streaming the proceedings online. This review is based on viewing the conference as it was streamed online.

The aim of the conference was to highlight both experimental research, and the value of experience gained through working with ancient materials and techniques. In addition to conventional papers, participants were encouraged to include physical demonstrations. The conference was also made available to a wider audience by streaming the proceedings online. This review is based on viewing the conference as it was streamed online.

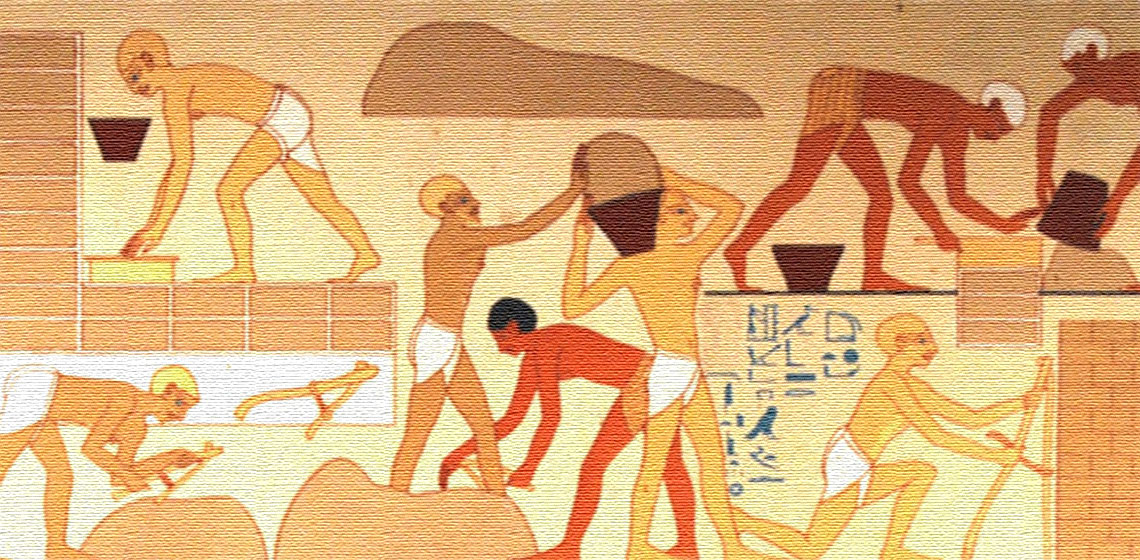

Many of the papers focused on a diverse array of materials and processes including ship-building (Creasman), lithics and stone (Lund, Cwiek, Stocks), woodworking (Killen) textiles (Janssen, Richards, Johnstone), garlands (McAleely), glass (Nicholson), metal (Merkel) and ceramic (Szpakowska). Many of the papers included demonstrations of the skills or materials associated with their topic. For example, Geoffrey Killen demonstrated with ancient Egyptian tools, including a replica lathe based on ancient illustrations, and Marquardt Lund (Flint Knapping Scenes from Beni Hassan Tombs) also included demonstrations of knapping.

While most of the demonstrations were more experiential in nature, a few aimed to answer archaeological questions through experiment. Rosalind Janssen (Textile Demonstration) used volunteers to create pleats in linen using both a replica laundry and by hand so as to compare the two processes, while Salima Ikram (From the Meadow to the Em-baa-ming Table: Experimental Archaeology and Mummification) tested the hypothesis that an alabaster containers can be stained with blood. Wileke Wendrich’s study of apprenticeship through ethnography served as a reminder that the people that produced the materials that are studied through experiment often had years of experience and knowledge often unavailable to present researchers.

Several papers also explored the historical significance of both experimental archaeology and experiential studies in Egyptology. Donald Ryan (Reed Boat Building: Early Experiments) recounted the work of Thor Heyerdahl, including that which had tenuous links to Egyptology. Ashley Cooke (The Experimental Work of FCJ Spurrell: Faience, Glass and Beads) and Carolyn Graves-Brown (History of Experimental Lithics: From Spurrell to Lund) highlighted the important historical role of experiment/experience in archaeological research, and Egyptology in particular.

The inclusion of demonstrations in many of the presentations was a welcome change, and several of the presenters were able to skillfully employ conventional methods with showing off skills or answering archaeological questions. This was aided by the fact that most papers were allotted 40 minutes to an hour. However, some papers would have benefitted from being kept to a more traditional time allowance of 20 to 30 minutes. This may have allowed for part of the conference to be dedicated to more in-depth demonstrations or experiments. The decision to make the conference available online was a good one that should be made more often for smaller conferences such as this. Online streaming, or similar techniques such as podcasts, make such conferences more accessible to students and to researchers located abroad. While much of the conference focused on experience rather than experiment, it was able to highlight the importance of such work and that fact that such experience is often needed to construct viable archaeological experiments.

Keywords

Country

- Egypt

- United Kingdom